Engineers have long known how to steer electricity in one direction, but heat has been far harder to tame. Now a new one-way thermal “diode” promises to give designers similar control over heat flow, opening a path to batteries and electronics that can keep working in brutal cold or blistering heat.

By forcing heat to move preferentially from hot to cold while blocking the reverse, the device could let high performance batteries run cooler under stress yet stay warm enough to function in deep freeze conditions. If the technology scales, it could reshape how I think about everything from electric vehicles to AI data centers that are straining against thermal limits.

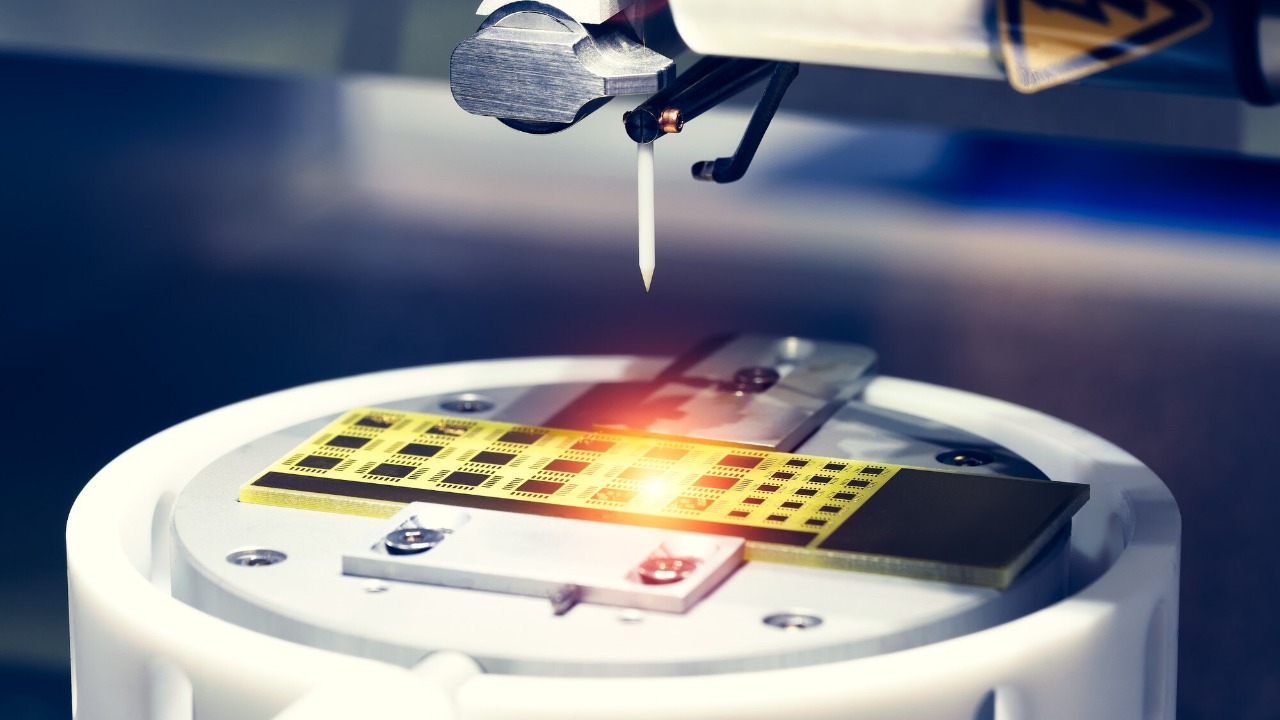

How a one-way heat diode actually works

The core idea behind the new device is deceptively simple: create a structure that lets heat pass easily in one direction but resists it in the other, much like an electrical diode does for current. Researchers at the University of Houston have now demonstrated such a one-way heat diode, giving engineers a new tool to manage temperature in systems that operate under extreme conditions. Instead of relying only on fans, coolant loops, or bulky insulation, designers can start to think in terms of routing thermal energy along preferred paths.

At the heart of the work is a carefully engineered material stack that changes how heat-carrying vibrations behave depending on direction. The team’s approach, described as a way to make heat flow in only one direction, effectively breaks the usual symmetry that makes thermal conduction reversible. That directional control is what allows the diode to keep a component from overheating while still preventing precious warmth from leaking away when the environment turns harsh, a balance that is especially valuable for batteries that must survive both scorching operation and frigid standby.

The Houston team behind the breakthrough

The advance comes from a group led by Bo Zhao, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering whose work focuses on thermal transport at the nanoscale. In a detailed account of the project, the Key Takeaways section highlights how Zhao and his colleagues built a platform that gives engineers new control over how devices shed or retain heat. By treating heat as something that can be directed with precision rather than as a byproduct to be dumped, they are reframing thermal management as a design parameter on par with voltage or clock speed.

Institutional backing has been central to pushing the concept from theory into a working prototype. The effort is rooted at the University of Houston, where Education leader Renu Khator President, University of Houst, has emphasized research that directly addresses real world energy and climate challenges. That institutional focus helps explain why the team has been quick to connect its thermal diode concept to practical use cases like batteries, power electronics, and other systems that must operate reliably in a very hot environment.

Why batteries need one-way heat control

Modern lithium ion packs are remarkably capable, but they are also thermally fragile. Push a battery in a high performance electric vehicle or a fast charging smartphone and it generates intense heat that must be pulled away quickly to avoid degradation or, in worst cases, thermal runaway. At the same time, those same cells can lose capacity and even fail to operate if they are allowed to get too cold, which is why drivers of cars like the Tesla Model Y or Ford F 150 Lightning see reduced range in winter and why manufacturers add complex heaters and coolant loops to keep packs in a narrow comfort zone.

The one way heat diode developed in Jan at the University of Houston is aimed squarely at this dilemma. By letting heat escape efficiently when a battery is working hard, then throttling the reverse flow when the environment is freezing, the device could help packs run cooler under load yet stay warm enough to deliver power in subzero conditions. Reporting on the technology notes that this directional control could help batteries survive extreme operating conditions and improve thermal management in high stress environments, a category that includes not only electric vehicles but also grid scale storage banks and aerospace systems that cycle between sun baked and cryogenic temperatures.

From EVs to AI data centers

The most obvious beneficiaries of a practical thermal diode are electric vehicles, which juggle performance, range, and longevity under wildly varying climates. A pack in a Chevrolet Bolt EUV parked in Phoenix summer heat faces very different stresses from one in a Hyundai Ioniq 5 fast charging at a ski resort, yet both must meet the same safety and warranty expectations. If automakers can embed one way heat paths into battery modules, they could simplify cooling hardware, reduce energy spent on active thermal management, and potentially extend cell life by keeping temperatures in the sweet spot more consistently.

The same logic applies to the racks of processors that power AI workloads. The Key Takeaways from the Houston team’s work explicitly point to a new approach to AI data centers, where dense clusters of accelerators like Nvidia H100 units are already straining conventional cooling systems. By steering heat away from the hottest chips while preventing cold spots that can cause condensation or mechanical stress, a thermal diode network could let operators pack more compute into the same footprint without resorting to exotic immersion cooling or relocating facilities to colder climates.

What still needs to happen next

For all its promise, the one way heat diode is still at an early stage, and scaling it from laboratory samples to industrial hardware will not be trivial. Manufacturers will need to prove that the material structures can be produced at volume, integrated into existing battery housings or server chassis, and survive years of thermal cycling without losing their directional behavior. Reliability standards in sectors like automotive and aviation are unforgiving, and any new component that touches safety critical systems must clear extensive validation before it appears in a production vehicle or aircraft.

There is also the question of cost and system level design. Even if the diode itself is relatively inexpensive, engineers will have to rethink layouts to take full advantage of one way heat paths, which could mean redesigning battery modules, power electronics boards, or server racks from the ground up. Yet the fact that Jan and the University of Houston team have already demonstrated a working device and framed its potential across batteries, Education applications, and AI infrastructure suggests that the concept is more than a curiosity. If the technology matures, I expect it to become part of a broader toolkit that treats heat not as an unavoidable nuisance but as a resource that can be routed, stored, and used with the same intentionality as electrical power.

More from Morning Overview