The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is being built to map the universe on a scale no previous observatory has attempted, and that ambition extends deep into the hearts of stars. By watching tiny rhythmic flickers in stellar brightness across vast swaths of the Milky Way, Roman is poised to assemble the largest asteroseismic catalog ever, turning whole regions of the sky into a laboratory for stellar interiors. That haul will not just refine models of how stars live and die, it will also sharpen the cosmic yardsticks that underpin modern cosmology.

Roman’s wide-field design turns asteroseismology into a survey science

The core reason Roman can promise an unprecedented asteroseismic harvest is its combination of sensitivity and field of view. Where missions like Kepler and TESS monitored relatively small patches of sky at a time, Roman’s wide-field instrument is engineered to capture dense star fields in a single pointing, tracking subtle brightness variations across millions of stars at once. That design, paired with long, repeated observations, is what allows asteroseismology to shift from a boutique technique applied to select targets into a survey-scale tool that can characterize stellar interiors across the galaxy.

Mission planners expect those brightness oscillations to reveal internal densities, rotation rates, and evolutionary stages for stars that would otherwise be little more than points of light, and they frame this as a natural extension of Roman’s broader mandate to study the structure and history of the Milky Way. NASA describes how the observatory will deliver “new waves of information” on the galaxy’s stars by combining precise photometry with large-area mapping, a capability that directly feeds asteroseismic work on red giants and other luminous tracers of galactic structure, as detailed in its overview of Roman’s stellar science.

Peering through dust to reach the galaxy’s hidden oscillating stars

To build a truly representative asteroseismic sample, Roman has to see stars that are currently buried behind curtains of interstellar dust. Its infrared vision is tuned precisely for that task, allowing the telescope to peer into the crowded, reddened regions of the galactic plane and bulge where dust blocks visible light. By operating at these longer wavelengths, Roman can monitor the brightness of stars that have been largely inaccessible to previous optical missions, extending asteroseismology into environments where stellar evolution is shaped by dense gas, strong tidal fields, and frequent interactions.

That dust-piercing power is not just a side benefit, it is central to Roman’s survey strategy. The mission team has laid out how mapping the distribution and properties of cosmic dust will help reconstruct the three-dimensional structure of the Milky Way, and those same observations will carry the high-cadence photometry needed to track stellar pulsations. In practice, that means asteroseismic measurements will be embedded in a broader campaign to “unveil our home galaxy” using infrared light that can slip past dust grains, as described in the mission’s plans for using cosmic dust as a tracer.

From stellar quakes to cosmic history

Asteroseismology is often framed as a way to weigh and age individual stars, but in Roman’s case the stakes are larger, because those stellar properties feed directly into measurements of the universe itself. By pinning down the masses and ages of standard-candle stars, especially red giant branch and red clump populations, Roman’s oscillation data will refine distance estimates across the Milky Way and beyond. Those improved distances, in turn, tighten constraints on the expansion history of the universe and the behavior of dark energy, which is a central pillar of Roman’s cosmology program.

The mission’s science team has emphasized that Roman is designed to uncover “echoes” of the universe’s earliest moments by mapping how matter clumped and evolved over cosmic time, and precise stellar distances are one of the tools that make that reconstruction possible. Asteroseismic ages for large samples of stars will help chart when different parts of the galaxy formed, providing a fossil record that can be compared with large-scale structure surveys and supernova distance ladders. That connection between stellar quakes and the early universe is explicit in Roman’s plans to uncover echoes of creation through wide-field, high-precision measurements.

Engineering a survey built for precision light curves

Delivering the biggest asteroseismic haul is not just a matter of pointing Roman at the right stars, it depends on engineering that can hold the telescope steady and calibrate its detectors to exquisite levels. The observatory’s wide-field instrument is designed to produce stable, repeatable photometry across its entire field, so that tiny oscillation signals are not swamped by instrumental noise or pointing jitter. That stability is particularly important for long-period pulsations in evolved stars, which require uninterrupted monitoring over weeks or months to disentangle overlapping modes.

Roman’s project documentation highlights how the mission’s optical design, thermal control, and detector systems are being tuned to support both its dark energy surveys and its time-domain work, including microlensing and variable-star science. The same hardware that will track subtle gravitational lensing distortions in distant galaxies will also capture the minute brightness variations of nearby stars, enabling asteroseismology at scale. Technical briefings from the mission’s science operations center describe how the observatory’s field of view and sensitivity compare with Hubble and other facilities, underscoring why Roman is often described as a wide-field complement to existing space telescopes in materials hosted by the Space Telescope Science Institute.

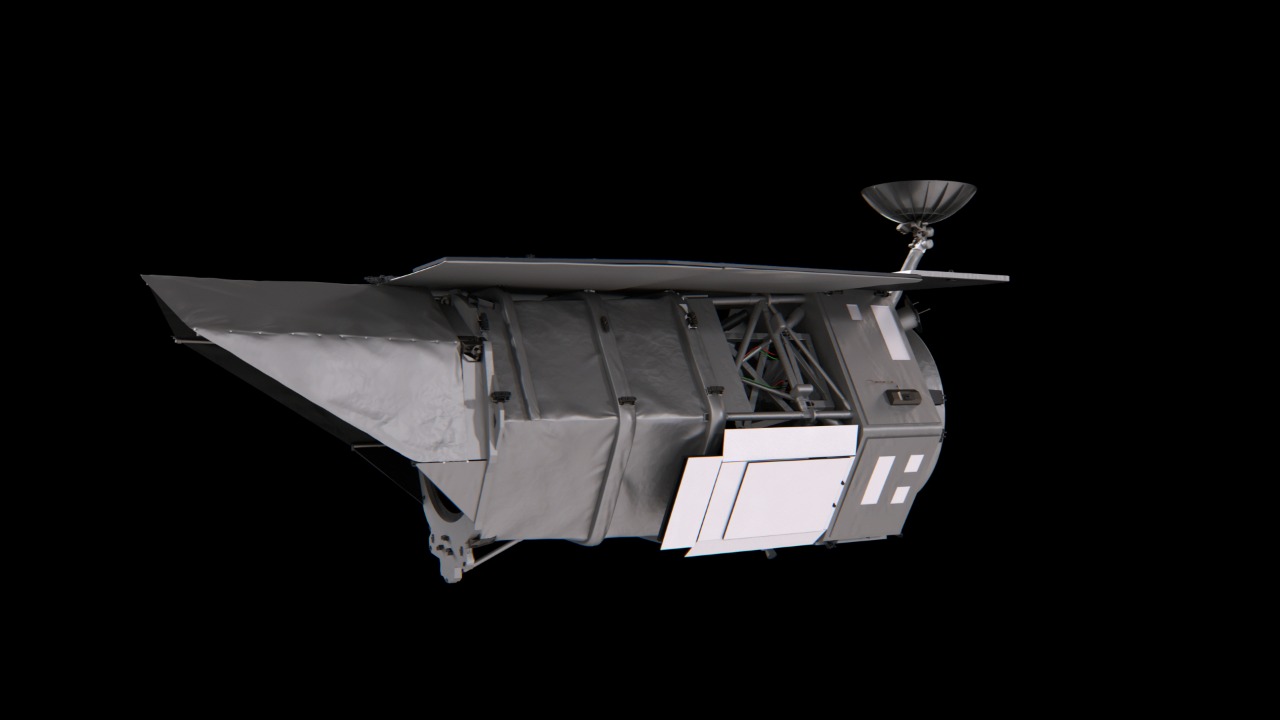

Mission status and the path to first stellar quakes

Roman’s promise for asteroseismology depends on a complex development pipeline that is now moving through integration and testing. Hardware updates and schedule briefings show key components, including the wide-field instrument and spacecraft bus, progressing toward launch readiness, with teams focused on verifying that the observatory can meet its stringent pointing and stability requirements. Those milestones are critical, because any unanticipated noise sources would directly erode the quality of the light curves that asteroseismology relies on.

Recent mission updates shared with the public have highlighted winter and spring 2025 as a period of intense activity, with engineers running through environmental tests and rehearsing operations that will later support large-area surveys of the Milky Way. In those briefings, project scientists have reiterated that Roman’s time-domain programs, including variable-star monitoring, are integral to the mission rather than an afterthought, and they have used simulated data to illustrate the kind of oscillation signals the telescope is expected to capture. A video update circulated by mission supporters outlines this testing phase and previews the observing campaigns that will follow, as seen in the winter and spring 2025 Roman mission update.

Roman’s broader science portfolio strengthens its stellar work

Roman’s asteroseismic ambitions are strengthened by the fact that the mission is not a single-purpose observatory, but a multi-pronged survey platform. Its primary science themes include probing dark energy, conducting a census of exoplanets through microlensing, and mapping the structure of the Milky Way, all of which require the same kind of precise, repeated imaging that asteroseismology needs. That overlap means stellar oscillation studies will benefit from data collected for other programs, turning every deep, time-resolved field into an opportunity to extract more information about stellar interiors.

The mission’s official materials describe a suite of surveys that will repeatedly scan dense star fields toward the galactic bulge and disk, generating light curves for countless stars that can be mined for oscillation signatures. Those plans are laid out in detail on the project’s main site, which explains how Roman’s wide-field instrument and observing strategy are optimized for both cosmology and galactic archaeology. By design, the same datasets that reveal dark matter through weak lensing and exoplanets through microlensing will also feed the largest catalog of stellar pulsations yet assembled, as outlined in the mission overview on the Roman project site.

Synergy with other observatories and planetary defense

Roman’s time-domain strengths will not operate in isolation, they will complement other observatories that monitor variable objects and moving targets across the sky. While its primary focus is cosmology and galactic structure, Roman’s wide-field imaging and precise astrometry can also contribute to tracking near-Earth objects and characterizing small bodies, which has led mission planners to explore how the telescope can support planetary defense efforts. Those same capabilities, particularly the ability to measure subtle brightness changes and motions, are directly relevant to asteroseismology, since they demonstrate the observatory’s sensitivity to small, time-varying signals.

Analyses of Roman’s potential role in monitoring asteroids emphasize how its survey fields and cadence could be leveraged to spot and refine orbits for objects that pose a risk to Earth, effectively adding the telescope to the broader network of planetary defense assets. That discussion underscores Roman’s versatility as a facility that can serve multiple communities, from stellar physicists to planetary scientists, using the same underlying data streams. The prospect of Roman joining Earth’s “asteroid defence team” illustrates how its high-precision photometry and astrometry can be repurposed beyond its core cosmology goals, as explored in assessments of Roman’s asteroid defense role.

Public engagement and the story behind the name

Part of what makes Roman’s asteroseismic potential compelling is the story behind the mission’s name. The observatory honors Nancy Grace Roman, the astronomer who played a pivotal role in planning and advocating for the Hubble Space Telescope and who is often referred to as NASA’s first Chief of Astronomy. Naming a wide-field, survey-driven mission after someone who championed space-based astronomy underscores the agency’s intent to build on that legacy, extending precision astrophysics from narrow, deep fields to panoramic views of the cosmos that include millions of stars suitable for asteroseismology.

Background materials on the mission’s naming explain how Nancy Grace Roman’s work in the mid-20th century helped establish space telescopes as essential tools for astrophysics, paving the way for facilities that can now probe stellar interiors and cosmic expansion with unprecedented detail. The telescope that bears her name is designed to operate at the Sun-Earth L2 point, using a 2.4-meter mirror and a wide-field instrument to conduct its surveys, and its asteroseismic output will be one of the most direct ways the public can see stars as dynamic, vibrating spheres rather than static points. That historical context is captured in the mission’s biographical and technical overview on the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope page.

How Roman’s data will reach the asteroseismology community

For Roman to truly transform asteroseismology, its data must be accessible and usable by a broad community of researchers. Mission planners have outlined a data pipeline that will process raw images into calibrated products and light curves, which can then be analyzed for oscillation signals using established techniques and new machine-learning tools. The expectation is that large, homogeneous datasets will enable statistical studies of stellar populations, allowing researchers to compare oscillation properties across different regions of the galaxy and different evolutionary stages.

Science operations centers and partner institutions are already preparing software and infrastructure to handle the anticipated data volume, drawing on experience from previous missions that produced massive time-domain datasets. Public presentations and technical talks have highlighted how Roman’s light curves will be distributed and how community members can propose complementary observations from ground-based telescopes and other space missions. A recorded briefing on the mission’s science goals and operations describes these plans in the context of Roman’s broader survey strategy, including its role in time-domain astronomy, as discussed in a detailed Roman science overview.

Looking ahead to the first stellar oscillation maps

Once Roman is on orbit and its surveys are underway, the first asteroseismic results are likely to focus on well-studied stellar populations where existing models can be tested and refined. That includes red giants in the galactic bulge and disk, where oscillation patterns can be compared with previous measurements from missions like Kepler, as well as younger stars in star-forming regions that Roman can access through dust. Over time, as more fields are observed and re-observed, the mission will build a layered map of stellar oscillations that traces how the Milky Way assembled its mass and metals.

Mission scientists have used simulations and visualizations to illustrate what those future maps might look like, showing how oscillation-derived ages and masses can be plotted across the galaxy to reveal gradients and substructures. Public-facing videos walk through these scenarios, connecting the technical details of Roman’s instruments to the broader narrative of understanding our place in the cosmos through the vibrations of distant suns. One such presentation outlines the mission’s capabilities and anticipated discoveries, including its role in time-domain and stellar astrophysics, in a comprehensive Roman mission presentation.

Roman’s place in NASA’s evolving observatory fleet

Roman is emerging at a moment when NASA’s fleet of space observatories is shifting from single-target, narrow-field instruments to survey-class facilities that can map large portions of the sky quickly. In that context, Roman is positioned as a wide-field counterpart to telescopes like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope, providing the statistical backbone that can guide more detailed, follow-up observations. For asteroseismology, that means Roman will identify vast samples of oscillating stars whose detailed spectra and high-resolution imaging can later be obtained with other observatories, creating a layered approach to stellar physics.

Institutional partners involved in Roman’s development have emphasized this complementary role, noting that the mission’s design was shaped by lessons learned from earlier space telescopes and by the scientific priorities laid out in decadal surveys. Documentation from these partners describes how Roman’s surveys will be coordinated with other facilities and how its data products will be structured to facilitate cross-mission analyses. The Space Telescope Science Institute, which has a central role in operating Hubble and JWST, outlines how it will support Roman’s science operations and community engagement, including for stellar and time-domain programs, in its dedicated Roman mission portal.

Asteroseismology as a flagship outcome, not a side project

As Roman moves closer to launch, it is increasingly clear that asteroseismology is not a niche add-on but a flagship outcome of the mission’s design choices. The combination of wide-field coverage, infrared sensitivity, and time-domain stability aligns almost perfectly with the needs of stellar oscillation studies, even though the mission was primarily framed around dark energy and exoplanets. That alignment reflects a broader trend in astrophysics, where multi-purpose survey telescopes are built to serve overlapping communities, maximizing scientific return from every photon collected.

NASA’s own descriptions of Roman’s stellar science emphasize that the mission will deliver transformative datasets on the structure and evolution of stars across the Milky Way, and that those datasets will be rich enough to support asteroseismic analyses at a scale never before attempted. As the observatory’s hardware comes together and its survey strategies are finalized, the prospect of mapping the galaxy’s internal vibrations is shifting from an aspirational goal to a concrete, near-term outcome. The agency’s mission pages frame this future in terms of a new era of wide-field astrophysics, with Roman at the center, as detailed in the comprehensive overview of the galaxy’s stars that the telescope will study.

More from MorningOverview