For more than a decade, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope has quietly mapped the high-energy sky, searching for subtle patterns in the cosmic glow. Now a new analysis of its data points to a tantalizing signal that could be the first direct glimpse of dark matter, the invisible substance thought to make up most of the universe’s mass. The claim is cautious but profound: a narrow spike in gamma rays that appears to match what theorists have long predicted for dark matter particles annihilating in space.

If this interpretation holds, it would mark a turning point in physics, transforming dark matter from a purely gravitational ghost into something that can be studied as a real particle. It would also validate a strategy that has driven Fermi’s mission from the start, using the sky itself as a detector to catch the rarest and most energetic events in nature.

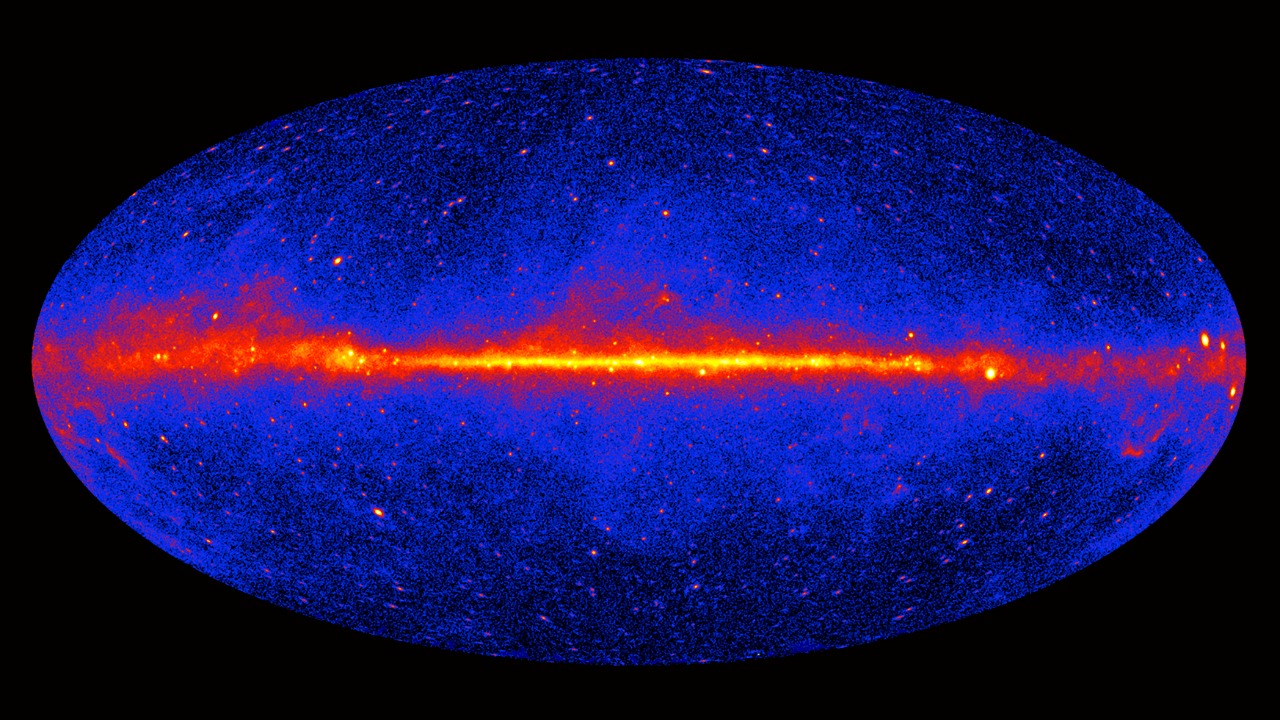

Fermi’s mysterious gamma-ray spike

The new excitement centers on a sharp feature in the gamma-ray spectrum, a narrow excess of photons at a specific energy that stands out from the smoother background glow. Researchers working with Fermi data report that this spike appears in the direction of the Milky Way’s center, where dark matter is expected to be densest, and that its energy lines up with long-standing predictions for certain dark matter candidates. The signal emerges from years of accumulated observations, carefully filtered to remove known astrophysical sources and instrumental artifacts, leaving behind a residual that is difficult to explain with conventional processes alone.

What makes this spike so compelling is not just its location but its shape. Ordinary astrophysical emitters, such as pulsars or supernova remnants, tend to produce broad spectra that fall off gradually with energy, while the reported feature looks more like a line, a hallmark of particle annihilation or decay. Several teams analyzing the same Fermi data have converged on a similar excess, strengthening the case that something unusual is happening in the galactic center region, as highlighted in detailed discussions of the gamma-ray spike near the Milky Way core.

Why dark matter hunters are so intrigued

For decades, dark matter searches have followed three main paths: underground detectors looking for rare particle collisions, particle accelerators trying to create dark matter in high-energy collisions, and telescopes scanning the sky for the byproducts of dark matter interactions. Fermi’s potential signal falls squarely in the third category, offering a possible indirect detection that could bridge the gap between astrophysics and particle physics. The reported gamma-ray line matches the kind of signature theorists expect if dark matter particles annihilate into photons with a characteristic energy, a scenario that has been modeled extensively but never clearly seen.

What sets this result apart from earlier hints is the combination of statistical strength, spectral sharpness, and alignment with theoretical expectations. Previous anomalies in the galactic center, such as broader excesses of lower-energy gamma rays, have often been attributed to unresolved populations of pulsars or other conventional sources. In contrast, the new feature looks more like the clean, monochromatic imprint of a particle process, which is why some researchers have described it as a potential first for humanity in actually seeing dark matter’s footprint in light, a possibility explored in depth in analyses of a candidate dark matter line in Fermi data.

How a gamma-ray telescope became a dark matter experiment

Fermi was not built solely as a dark matter machine, but its design makes it uniquely suited to the task. Orbiting Earth, the telescope continuously scans the sky for photons with energies far beyond visible light, mapping everything from flaring blazars to the diffuse glow of cosmic rays colliding with interstellar gas. By accumulating more than a decade of observations, Fermi has created a deep, all-sky dataset that allows scientists to search for faint, persistent patterns that would be invisible in shorter campaigns. The galactic center, though crowded and complex, has been a prime target because theoretical models predict that dark matter density should peak there.

Turning that raw gamma-ray map into a dark matter test requires careful modeling of every known source of high-energy photons, from star-forming regions to the interactions of cosmic rays with dust and gas. Researchers then subtract these modeled contributions from the observed data, looking for residuals that cannot be easily explained. The newly reported spike emerged from exactly this kind of painstaking background subtraction, which is why it has drawn so much attention from both astronomers and particle physicists who have long argued that a space-based gamma-ray observatory could double as a powerful dark matter detector, a dual role that has been emphasized in technical breakdowns of Fermi’s gamma-ray search for exotic particles.

What the signal might say about dark matter particles

If the gamma-ray spike is indeed produced by dark matter, it carries encoded information about the particles themselves. The energy of the line would correspond roughly to the mass of the dark matter particle, while the brightness of the signal would reflect how often those particles annihilate or decay. Early interpretations suggest a particle mass in a range that has been heavily studied in theoretical models, particularly those involving weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs, which have long been a leading candidate for dark matter. The apparent intensity of the signal, if confirmed, would also help pin down the interaction strength that governs how frequently dark matter particles collide and convert into light.

Those parameters matter because they can be compared directly with limits from other experiments, such as underground detectors that have so far failed to see convincing signs of dark matter collisions with ordinary matter. If Fermi’s signal points to a particle that should have been visible in those detectors but was not, it would force a rethinking of the underlying theory. On the other hand, if the inferred properties fit comfortably within existing bounds, it would provide a rare point of agreement between astrophysical and laboratory searches. That is why theorists are already poring over the reported line, using it to refine models of dark matter’s mass and interaction cross-section, a process described in recent coverage of how years of gamma-ray data are reshaping dark matter constraints.

Alternative explanations and the burden of proof

Despite the excitement, the community is far from declaring victory. Gamma-ray astronomy is notoriously tricky, and the galactic center is one of the most complicated regions in the sky. Small mismatches in how scientists model the diffuse background, or subtle quirks in the instrument’s response, can sometimes masquerade as real signals. Critics of the dark matter interpretation point out that Fermi has seen other apparent features in the past that faded with more data or improved analysis techniques. Any claim of a first direct dark matter signal therefore faces a high bar: it must survive repeated scrutiny, independent reanalysis, and cross-checks with other instruments.

Some researchers have suggested that unresolved populations of compact objects, such as millisecond pulsars, could still be contributing to the observed excess, even if they do not naturally produce such a sharp line. Others argue that the spike might be an artifact of how the data were binned or how the instrument’s energy resolution was handled. The teams behind the new analysis have tried to address these concerns by testing different modeling assumptions and by searching for similar features in other parts of the sky, where no comparable spike appears. That asymmetry, with a strong signal only toward the galactic center, is one reason they remain cautiously optimistic, a stance reflected in reports that describe the feature as a possible first glimpse rather than a definitive detection.

The Milky Way’s glow as a dark matter laboratory

The broader context for this discovery is the realization that the Milky Way’s diffuse gamma-ray glow is itself a rich laboratory for fundamental physics. By mapping how that glow changes with direction and energy, scientists can test models of cosmic-ray propagation, star formation, and the distribution of interstellar gas. Dark matter adds another layer to that picture, since its gravitational pull shapes the galaxy’s structure even if it does not emit light. The reported spike sits atop a complex background of emission that must be understood in detail before any exotic explanation can be trusted.

Over the past several years, improved models of the galactic center have already transformed earlier claims of dark matter signals, showing that some broad excesses could be explained by more mundane astrophysics. The new line feature, if it holds up, would be different in character, more like a narrow fingerprint than a general glow. That is why some astronomers see it as a potential turning point in how we read the Milky Way’s high-energy map, with one recent analysis arguing that the galaxy’s central emission may finally contain a distinct dark matter imprint within its overall gamma-ray glow.

Inside the team making the claim

Behind the new result is a small group of researchers who have spent years immersed in Fermi’s data, refining their methods and testing every possible source of error. One of the lead scientists has described the experience of isolating the spike as a kind of slow-motion revelation, with the feature growing more robust as more data were added and as the background models improved. The team has emphasized that they approached the analysis with skepticism, fully aware of the field’s history of false starts, and that they only went public once they were convinced that the signal could not be easily dismissed as a statistical fluke.

The personal stakes are high, not just scientifically but professionally. Claiming a first-of-its-kind detection invites intense scrutiny, and the researchers know that their work will be reanalyzed by colleagues around the world. One member of the team has even been described as potentially becoming the first person to have directly “seen” dark matter in the form of this gamma-ray signature, a label that underscores both the ambition and the risk of the claim, as highlighted in profiles of the scientist who may be the first to identify a dark matter signal.

What comes next for Fermi and beyond

The immediate next step is replication. Other groups are already digging into the same Fermi dataset, applying different analysis pipelines to see whether they recover the same spike with comparable significance. The Fermi collaboration itself will likely conduct its own internal checks, revisiting instrument calibrations and background models to rule out any overlooked systematics. At the same time, ground-based gamma-ray observatories and upcoming missions will be watching the galactic center with renewed interest, looking for complementary signatures at similar or higher energies that could either bolster or challenge the dark matter interpretation.

Even if the signal survives, it will not stand alone as proof. Physicists will want to see consistent hints in other channels, such as neutrinos or cosmic rays, and they will push underground detectors and collider experiments to test the particle properties implied by the gamma-ray line. The hope is that a coherent picture will emerge, with multiple lines of evidence converging on the same dark matter candidate. That multi-pronged strategy is already shaping plans for future instruments and surveys, as described in technical discussions of how Fermi’s potential detection could guide next-generation dark matter searches across different experiments.

Why this moment matters for cosmology

Regardless of the final verdict on the gamma-ray spike, the episode highlights how close cosmology may be to turning dark matter from an abstract placeholder into a concrete part of the particle zoo. For decades, the evidence for dark matter has been overwhelmingly gravitational: galaxy rotation curves, gravitational lensing, and the cosmic microwave background all point to a dominant invisible component. A spectral line in Fermi’s data, if confirmed as dark matter, would add a new kind of evidence, one rooted in particle interactions rather than just mass. That shift would open the door to laboratory-style studies of dark matter properties, from self-interactions to possible decays.

It would also reshape how we think about the universe’s evolution, since the behavior of dark matter particles in the early cosmos influences everything from the formation of the first galaxies to the distribution of large-scale structure today. A confirmed detection would feed directly into simulations and theoretical models, tightening constraints on scenarios that range from warm dark matter to more exotic hidden sectors. That is why some commentators have framed the Fermi result as a potential watershed for cosmology, suggesting that astronomers may have finally seen dark matter in a way that connects cosmic structure to particle physics.

A cautious step toward the invisible universe

For now, the Fermi gamma-ray spike sits in a familiar scientific limbo: too intriguing to ignore, not yet solid enough to claim as a discovery. The history of dark matter research is littered with anomalies that faded under scrutiny, and the community has learned to treat every new hint with a mix of curiosity and skepticism. Yet there is also a sense that the tools have finally matured, that long-running missions like Fermi are reaching the sensitivity needed to catch the universe in the act of revealing its hidden components.

Whether this particular signal stands or falls, it demonstrates the power of patient, data-driven astronomy to probe questions once thought beyond reach. A space telescope designed to map violent cosmic explosions may now be brushing against the edges of a deeper mystery, turning the Milky Way’s high-energy glow into a window on the invisible matter that holds the galaxy together. That possibility alone is enough to keep scientists poring over every photon, searching for the subtle patterns that might, at last, bring dark matter into the light, a quest that has already led to reports of a likely first glimpse of the elusive component in Fermi’s data.

More from MorningOverview