Solid-state batteries promise safer, lighter, and more energy-dense power packs for everything from smartphones to long-range electric cars, yet their real-world performance keeps falling short of the lab hype. A growing body of research now points to a subtle culprit: tiny structural defects at the nanoscale that quietly sabotage how ions move through these solid materials. As researchers probe these hidden flaws with ever finer tools, they are starting to map out how microscopic changes ripple up into macroscopic limits on durability, charging speed, and safety.

Instead of a single breakthrough material, the emerging picture is of a complex, multiscale engineering problem where atomic-level disorder, grain boundaries, and interfacial reactions all conspire to block the path to tougher, longer-lasting solid-state cells. I want to unpack how those nanoscale obstacles work, why they matter for the next generation of electric vehicles and grid storage, and how new imaging and data tools are giving scientists a clearer view of what has been holding solid-state batteries back.

Why solid-state batteries still lag their promise

For more than a decade, solid-state batteries have been framed as the logical successor to today’s lithium-ion cells, replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with solid ceramics or polymers that should, in theory, allow higher energy density and better safety. In practice, however, many prototype cells struggle with rapid capacity fade, limited cycle life, and mechanical failure once they are scaled beyond coin-cell formats. The gap between theoretical performance and what engineers can actually deliver at pack level suggests that the limiting factor is not just chemistry on paper, but the way that chemistry organizes itself in three dimensions at very small scales.

When I look at the latest experimental work, a consistent theme emerges: the solid electrolyte and electrode materials do not behave as uniform, ideal crystals. Instead, they develop local regions of strain, disorder, and phase change that distort the pathways lithium ions are supposed to follow. Recent nanoscale imaging of solid-state cells shows that even small variations in composition or structure can create bottlenecks where ions pile up, triggering side reactions and mechanical stress that accelerate degradation over repeated charge and discharge cycles, as detailed in new analyses of nanoscale changes inside working cells.

The hidden architecture of solid electrolytes

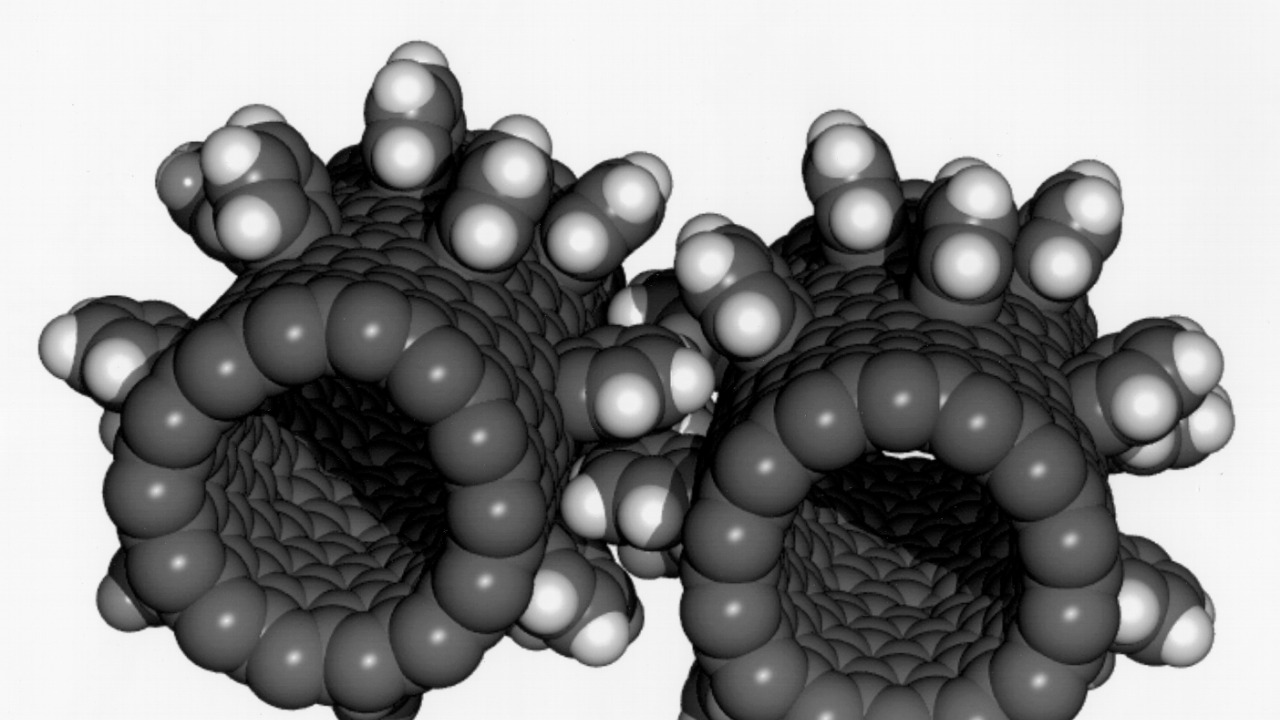

At the heart of the problem is the solid electrolyte, the material that must shuttle ions between the cathode and anode while blocking electrons. On paper, many sulfide and oxide electrolytes offer excellent ionic conductivity, rivaling or even surpassing liquid electrolytes. Yet those bulk measurements often mask a complex internal architecture of grains, grain boundaries, and defects that can dramatically alter how ions move in real devices. The idealized crystal lattice that appears in diagrams is only part of the story; the real material is a patchwork of slightly misaligned regions stitched together by interfaces that can either help or hinder ion transport.

High-resolution studies of these materials show that grain boundaries can act as both highways and roadblocks, depending on their chemistry and structure. In some solid electrolytes, boundaries provide fast diffusion channels, while in others they trap ions or accumulate decomposition products that raise resistance over time. The latest operando experiments, which track structural evolution during cycling, reveal that these boundaries are not static; they can widen, crack, or even transform into new phases under the stress of repeated lithium insertion and extraction, a dynamic behavior that helps explain why nominally similar materials can perform so differently once integrated into full cells and subjected to realistic operating conditions.

Nanoscale defects as ion traffic jams

To understand why a seemingly minor defect can have outsized impact, it helps to think of ion transport as a network problem rather than a simple straight line. In a dense solid, lithium ions hop from site to site along percolating pathways that must remain continuous across the entire thickness of the electrolyte. A single region of poor conductivity, even if it occupies only a small volume fraction, can choke off current flow if it sits in a critical part of that network. Nanoscale voids, dislocations, or chemically altered pockets effectively act as traffic lights in what should be a free-flowing highway system for ions.

Recent imaging work shows that these defects often cluster near interfaces or in regions that experience the highest mechanical stress, such as where the solid electrolyte meets a high-capacity cathode. As cycling proceeds, local strain can concentrate around these weak points, amplifying the initial imperfection into a larger crack or phase-separated zone that further impedes ion motion. Over dozens or hundreds of cycles, the result is a patchwork of active and inactive regions inside the cell, with current forced through narrower and narrower channels. That uneven current distribution not only raises resistance and heat generation, it also increases the risk of localized failure modes that can compromise safety.

Interfaces: where chemistry and mechanics collide

Many of the most stubborn problems in solid-state batteries arise at the interfaces between different materials, particularly where the solid electrolyte meets the cathode and anode. These boundaries must simultaneously accommodate ion transfer, electronic insulation, and mechanical contact, all while enduring repeated volume changes as lithium content fluctuates. In practice, that combination is difficult to sustain. Even small mismatches in thermal expansion or lattice spacing can generate stress that leads to debonding or microcracking at the interface, creating gaps that ions cannot easily cross.

Chemistry adds another layer of complexity. Some solid electrolytes are thermodynamically unstable against common cathode materials, leading to the formation of interphase layers that grow thicker with each cycle. While a thin, stable interphase can sometimes protect the underlying materials, uncontrolled reactions can produce resistive layers that act as additional barriers to ion flow. Nanoscale characterization of these interphases shows that they are often heterogeneous, with pockets of different composition and conductivity that further fragment the ion transport network. The interplay between mechanical damage and chemical evolution at these interfaces is increasingly seen as a central obstacle to achieving both high energy density and long cycle life in practical solid-state cells.

Mechanical stress and the risk of cracks

Unlike liquid electrolytes, which can flow to relieve stress, solid electrolytes must absorb the full brunt of the mechanical forces generated during battery operation. High-capacity electrodes, particularly those based on silicon or high-nickel oxides, undergo significant volume changes as they alloy with lithium or change oxidation state. When those expansions and contractions are constrained by a rigid solid electrolyte, the resulting stress can exceed the material’s fracture toughness, leading to the formation of microcracks that propagate over time.

Once cracks form, they create new internal surfaces that can react with the electrolyte or electrode, further altering local chemistry and conductivity. They also provide potential pathways for lithium filaments to grow, a failure mode that can short-circuit the cell even in systems designed to suppress traditional dendrites. Detailed nanoscale studies of cycled solid-state cells reveal networks of such cracks radiating from high-stress regions, often correlating with areas of elevated resistance and capacity loss. Managing this mechanical landscape, through both material choice and clever cell architecture, is therefore as important as optimizing ionic conductivity on paper.

How advanced imaging is exposing the nanoscale bottleneck

One reason these nanoscale flaws have taken so long to diagnose is that they are difficult to see without specialized tools. Conventional electrochemical measurements can flag that a cell is degrading, but they rarely pinpoint where or why. Over the past few years, researchers have increasingly turned to advanced imaging and spectroscopy techniques that can probe solid-state batteries in three dimensions and, crucially, under operating conditions. Methods such as synchrotron X-ray tomography, electron microscopy, and scanning probe microscopy are now being adapted to track structural and chemical changes at nanometer resolution while the cell is cycling.

These techniques are revealing a far more dynamic and heterogeneous picture of solid-state batteries than earlier models assumed. For example, operando X-ray studies show that regions of the solid electrolyte can undergo subtle phase transitions as a function of local lithium concentration, creating patches of altered conductivity that evolve over time. Electron microscopy of cross sections taken from cycled cells highlights how grain boundaries and interfaces gradually accumulate defects and reaction products, correlating with rising impedance. By combining these spatially resolved measurements with electrochemical data, researchers are starting to build a more complete map of how nanoscale changes translate into macroscopic performance limits, as highlighted in recent work on structural evolution inside complex systems.

Data, models, and the language of materials

As imaging and spectroscopy generate richer datasets, the challenge shifts from collecting information to interpreting it in a way that guides better materials design. I see a growing convergence between battery research and data-driven methods originally developed for natural language processing and other fields. In both cases, the goal is to extract meaningful patterns from large, high-dimensional datasets, whether those datasets describe words in a sentence or atoms in a crystal. Techniques that can embed complex structures into compact representations are becoming valuable tools for predicting how subtle changes in composition or processing will affect performance.

Some teams are already experimenting with machine learning models that treat sequences of atomic environments or processing steps in a way that loosely echoes how language models handle sequences of characters or tokens. The underlying idea is that local context matters: just as the meaning of a word depends on its neighbors, the behavior of a defect depends on its surrounding lattice and interfaces. Resources originally built for text analysis, such as curated character vocabularies, illustrate how careful encoding of basic units can unlock higher-level understanding. In materials science, analogous encodings of structural motifs and defect types are starting to feed into predictive models that can flag which nanoscale configurations are likely to cause trouble long before a cell is built and tested.

Design strategies to tame nanoscale flaws

Armed with a clearer view of where solid-state batteries fail, researchers are now testing design strategies that explicitly target nanoscale flaws rather than treating them as unavoidable noise. One approach focuses on engineering the microstructure of solid electrolytes to control grain size, orientation, and boundary chemistry. By tuning synthesis conditions, it is possible to promote textures that favor continuous ion pathways and suppress the formation of high-resistance boundary phases. Some groups are also exploring dopants that segregate to grain boundaries and stabilize them against both mechanical and chemical degradation, effectively turning a liability into an asset.

Interface engineering is another active front. Thin buffer layers, sometimes only a few nanometers thick, can be inserted between the solid electrolyte and electrodes to mitigate both mechanical mismatch and unwanted reactions. These layers are designed to be ionically conductive while blocking electron transfer and providing a more compliant contact that can absorb volume changes. In parallel, cell architectures that distribute stress more evenly, such as stack designs with graded compositions or flexible current collectors, aim to reduce the likelihood that any single region will accumulate enough strain to crack. The common thread in these strategies is an acknowledgment that the nanoscale structure is not a side detail but a primary design variable that must be controlled as carefully as overall composition.

From lab insight to real-world batteries

The practical question is how quickly these nanoscale insights can translate into commercial products that power real vehicles and devices. Scaling up solid-state batteries requires not only solving the scientific puzzles of ion transport and mechanical stability, but also integrating those solutions into manufacturing processes that are cost-effective and reliable. Techniques that work on small, meticulously prepared samples may not survive the transition to roll-to-roll production or large-format cells without modification. That is why many industrial efforts are now pairing materials innovation with process development, seeking ways to bake nanoscale control into every step from powder synthesis to final assembly.

Automakers and battery startups are watching these developments closely, since the payoff for a robust solid-state platform would be significant: higher energy density for longer-range electric cars, improved safety margins that simplify pack design, and potentially faster charging if ion transport bottlenecks can be cleared. Yet the same nanoscale flaws that limit performance in the lab could become even more problematic in mass production if they are not carefully managed. Variability in particle size, impurity levels, or interface quality across thousands of cells could translate into inconsistent lifetimes and safety profiles. The emerging consensus among researchers is that conquering these challenges will require a combination of advanced characterization, data-driven modeling, and disciplined engineering, all focused on the subtle defects that quietly dictate how tough a solid-state battery can really be.

Why the nanoscale will decide the solid-state race

Looking across the latest research, I see a clear shift in how the community frames the solid-state battery problem. Early narratives emphasized finding the “right” electrolyte chemistry or the “perfect” electrode pair, as if a single materials choice could unlock the technology. The new evidence suggests that even excellent chemistries will underperform if their nanoscale structure is not carefully controlled. Tiny flaws, from misaligned grains to unstable interphases, act as gatekeepers that determine whether ions can move freely or are trapped in local dead ends. In that sense, the race to commercialize solid-state batteries is increasingly a race to understand and engineer the invisible architecture inside these materials.

That perspective does not diminish the importance of discovering new compounds or optimizing known ones, but it reframes success as a multiscale challenge that runs from atomic bonding all the way up to pack design. As imaging tools, data methods, and fabrication techniques continue to improve, I expect more of the field’s breakthroughs to come from strategies that explicitly target nanoscale behavior, whether by stabilizing critical interfaces, smoothing out mechanical stress, or designing microstructures that guide ions along the most efficient paths. The recent focus on nanoscale evolution inside working cells underscores how much there is still to learn, but it also offers a roadmap: if we can see where the flaws form and how they grow, we can start to design them out of the next generation of solid-state batteries.

More from MorningOverview