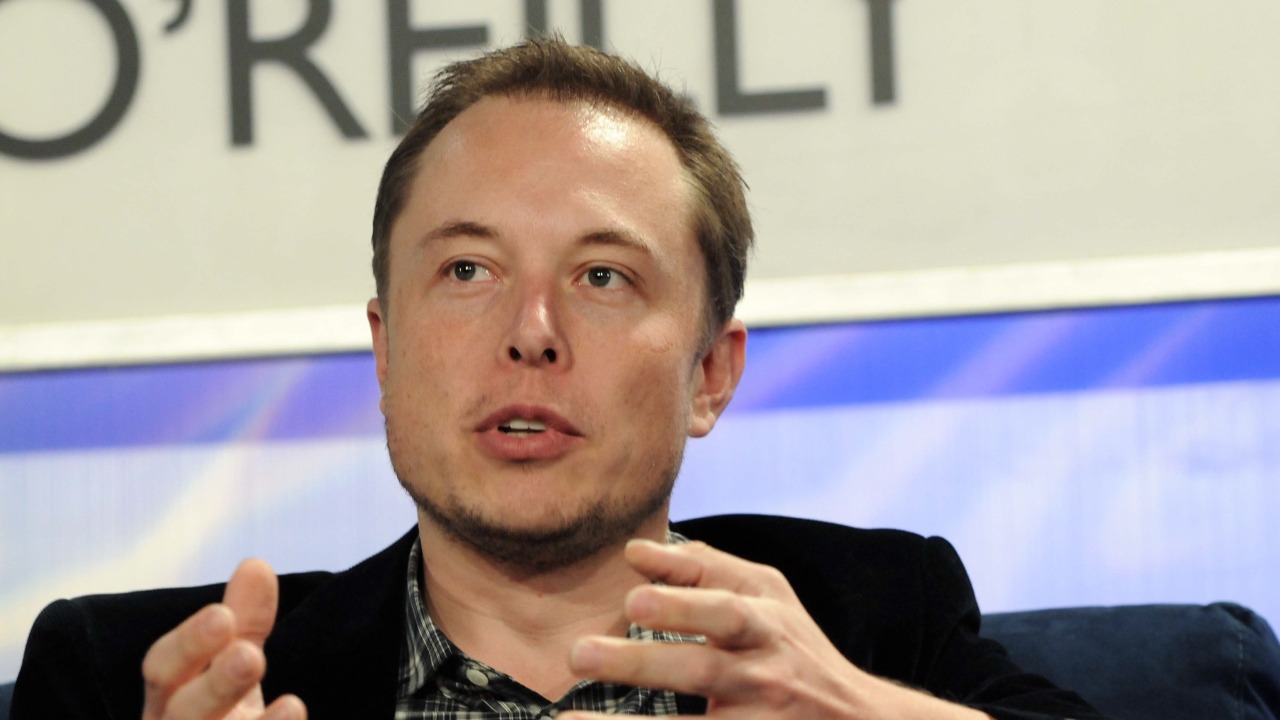

Elon Musk is pitching a future where artificial intelligence runs not in desert server farms but in orbit, powered directly by the sun. His vision of solar-fed data centers in space promises to ease pressure on Earth’s grids and water supplies, yet the engineers and analysts I spoke with see a thicket of technical, economic, and regulatory problems that could derail it long before the first orbital server rack boots up.

The idea taps into real concerns about the energy and cooling demands of AI, but it also collides with the messy realities of space hardware, radiation, and debris. As Musk races to turn concept into constellation, the gap between ambition and feasibility is becoming the central question.

The audacious plan: a million orbital data centers

Musk’s latest gambit builds on the existing Starlink model, but with a twist: instead of simply relaying internet traffic, a new generation of satellites would host full-fledged data centers in orbit. In filings and public comments, he has talked about a network of roughly 1 million satellites, each carrying compute hardware and drawing power from large solar arrays, effectively turning low Earth orbit into a vast cloud platform. The company behind the proposal, SpaceX, is already the dominant launcher of commercial satellites, which gives Musk a unique ability to deploy such a swarm if regulators sign off.

To move from rhetoric to reality, SpaceX has submitted an application to federal regulators describing a million-satellite orbital data center constellation and how it would operate. The plan, detailed in an application logged with the FCC, sketches out how these spacecraft would share spectrum, manage interference, and integrate with ground networks. Reporting on the filing notes that the company wants to leverage its existing launch cadence and manufacturing lines to mass-produce the new satellites, a strategy described in detail by Jeff Foust January. In a separate analysis of the regulatory paperwork, reporters Corbin Hiar, Ariel highlight how the proposal intersects with environmental and policy concerns raised by the administration of Presid Donald Trump, which is already grappling with the terrestrial footprint of AI infrastructure.

Why Musk says AI belongs in orbit

At the heart of Musk’s pitch is a simple claim: the world’s AI appetite is growing too fast for Earth’s energy and water systems to keep up. A large data center can use up to 5 million gallons of water per day, the equivalent to the water use of a town of 10,000 to 50,000 people, according to analysis of current facilities linked in Feb coverage. Musk argues that lifting compute into space, where solar power is abundant and uninterrupted by weather or night, could decouple AI growth from local water tables and fragile grids.

He has been explicit about that logic in recent statements, writing that “Space-based AI is obviously the only way to scale” and tying that directly to his solar ambitions in a post highlighted in Space. In a separate statement quoted in an industry-focused report, he framed “Space-based compute” as “the most efficient path forward for the next generation of artificial intelligence,” arguing that orbital systems can avoid the constraints of terrestrial power grids, a claim captured in a filing cited by Space. For Musk, the sales pitch is not just about spectacle, it is about convincing policymakers and investors that the only way to keep feeding AI models is to move the heaviest workloads off-planet.

Physics fights back: radiation, heat, and no repair crews

Experts who study spacecraft and high performance computing say the environment Musk wants to use is among the harshest imaginable for sensitive electronics. Critics point to “High radiation, extreme thermal swings (from +100 to -100°C over the course of minutes or hours) and micrometeoroids” as baseline conditions for hardware in low Earth orbit, a list of downsides spelled out in an engineering-focused discussion shared on Oct. Those swings alone would stress even hardened components, and the constant particle bombardment raises the risk of bit flips and permanent damage in densely packed AI accelerators.

Cooling is another place where intuition fails. Even though space is cold overall, cooling servers there is actually harder than on Earth, because there is no air to carry heat away and radiators must dump energy only through infrared emission. As one technical explainer puts it, “Cooling servers is harder without air,” and that single constraint cascades into heavier radiators, more complex thermal loops, and stricter power budgets, all of which are flagged as key challenges for space data centers in a detailed note from Cooling. On top of that, there are no repair crews in orbit, so any failure could mean losing an entire satellite, a risk highlighted in a breakdown of orbital maintenance limits that notes typical spacecraft have a lifespan of about five years, a figure cited in Here. Packing expensive AI chips into such a disposable platform is a very different proposition from swapping a failed rack in a warehouse outside Phoenix.

Space junk, rivals, and skeptical analysts

Even if the hardware worked flawlessly, a million new satellites would reshape the orbital environment and the competitive landscape. Space policy specialists already worry about congestion and collision risk from existing constellations, and a vast new fleet of compute nodes would multiply those concerns. Analysts and experts have been blunt about the safety and technical hurdles, with one assessment noting that “Analysts and experts point to major safety and technical hurdles” in CEO Elon Musk’s vision for a network of orbiting data centers, a judgment captured in a detailed review of the proposal linked through Analysts and. Some of those same observers warn that constant launches and deorbiting of short-lived satellites could worsen the debris problem that already threatens long term access to low Earth orbit.

Musk is also not alone in eyeing orbital infrastructure. And Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin announced plans in January for a constellation of more than 5,000 satellites to start launching late next year, a rival project that would add its own mass of hardware to the same orbital bands, according to a summary of those plans in And Jeff Bezos. Financial analysts are urging caution as the arms race accelerates. Despite the enthusiasm around space-based compute, “Despite the optimism, major analysts and scientists urge caution,” with Deutsche Bank’s Edison Yu singled out as one of several experts warning about constant bombardment by cosmic rays and the cost of hardening hardware against it, concerns laid out in a sober assessment from Despite the. On investor forums, some longtime followers are even more blunt, with one discussion thread titled “Thoughts on Musk’s claims about orbital data centers?” arguing that Back in November, Musk made promises that either reflect deep optimism or risk misleading investors, a tension captured in a candid debate on Thoughts.

Regulators, politics, and what happens next

For all the engineering drama, the immediate gatekeepers are regulators and politicians who must decide whether to let a million-server swarm take shape overhead. The Federal Communications Commission will have to weigh spectrum use, interference, and orbital debris mitigation before approving the constellation, and its public docket, accessible through the main spacenews.com coverage and the agency’s own FCC portal, is already drawing comments from competitors and environmental groups. The administration of Presid Donald Trump, which is simultaneously pushing for more domestic AI capacity and tighter control over critical infrastructure, will also have a say in how aggressively agencies scrutinize the project, a tension highlighted in policy-focused reporting that links the filing to broader White House priorities in EST.

More from Morning Overview