A volatile region on the Sun has just fired off a monster solar flare, followed by a blast of charged particles that space-weather scientists liken to a colossal “sun burp.” That outflow, a coronal mass ejection, is now racing toward our planet and is expected to brush past Earth, with the potential to trigger radio blackouts, disrupt navigation signals, and light up the skies with vivid auroras. While this is not the worst-case solar superstorm experts fear, it is a sharp reminder that our wired world is tethered to the moods of our star.

The eruption caps an already intense start to the year, coming on the heels of the strongest solar radiation storm in more than two decades and a rapid escalation in activity from a single, unstable sunspot. I see this episode as both a real-time stress test of our infrastructure and a preview of what the peak of the current solar cycle could bring over the next few years.

The monster flare and the ‘sun burp’ aimed at Earth

The immediate trigger for the current alert is an active region on the solar surface known as sunspot 4366, which has grown quickly and become highly unstable. Earlier this week, that region produced at least four major X-class flares in just over 24 hours, according to a Key Points summary of the event. Another report on the same episode notes that these eruptions from sunspot region 4366 rank among the most energetic solar outbursts seen so far this year, underscoring how exceptional this burst of activity has been for the current cycle Sun Unleashes Record. In practical terms, that means a torrent of X-ray and ultraviolet radiation washed over the dayside of Earth within minutes, temporarily disturbing high-frequency radio communications.

What has grabbed even more attention, though, is the associated coronal mass ejection, the “sun burp” of magnetized plasma that followed. Space-weather forecasters say the rapid growth of sunspot 4366 has made it particularly prone to such eruptions, and on Sunday it released a total of 4 X-class flares along with 23 weaker M-class events, a pattern that culminated in a CME now expected to graze our planet Blackout-Causing. Forecasts indicate that this CME will deliver only a glancing blow rather than a direct hit, but even a side swipe can compress Earth’s magnetic field enough to spark geomagnetic storms and localized power or radio issues.

How this flare fits into a surging solar cycle

The current fireworks are not happening in isolation. The Sun is climbing toward the peak of Solar Cycle 25, the roughly 11-year rhythm in which its magnetic field flips and activity surges. Official tracking of solar-cycle progression shows that sunspot counts and flare rates have been running hotter than early forecasts suggested, a sign that this cycle may peak on the stronger side. A detailed overview of Solar Cycle 25 notes that it is the current numbered cycle since systematic sunspot records began in 1755 and is expected to continue until about 2030, which means the heightened volatility we are seeing now could persist for several more years Solar. In that context, the latest flare is less an outlier and more a preview of the new normal as the Sun approaches its magnetic climax.

Recent weeks have already delivered a taste of what that means for Earth. On January 18 and 19, Earth experienced the strongest solar radiation storm in more than 20 years, an event that showered the planet with high-energy particles and forced operators to adjust procedures for satellites and astronauts On January. A separate analysis of the current solar maximum explains that approximately every 11 years the Sun’s magnetic field reverses, with Solar Cycle 25 having started in December 2019, and that this phase is now delivering some of the most powerful flares seen in years Sun. Taken together, the radiation storm in January and the current “sun burp” from sunspot 4366 point to a cycle that is hitting its stride with potentially disruptive consequences.

Inside the flare: X-class power and a hyperactive sunspot

To understand why this event is drawing so much scrutiny, it helps to look at the details of the flares themselves. The most intense class of solar flares is labeled “X,” and earlier this week The Sun emitted three strong eruptions on Feb. 1 that peaked at 7:33 a.m. ET, 6:37 p.m. ET, and 7:36 p.m. ET, followed by a fourth strong flare on Feb. 2 The Sun. A related briefing from the same mission team notes that these four strong solar flares were all tied to the same active region and that their timing and intensity are being used to refine models of how energy builds and releases in the solar corona Sun releases. In plain language, the Sun has been firing off some of the most energetic bursts it is capable of producing, and it is doing so repeatedly from the same magnetic hot spot.

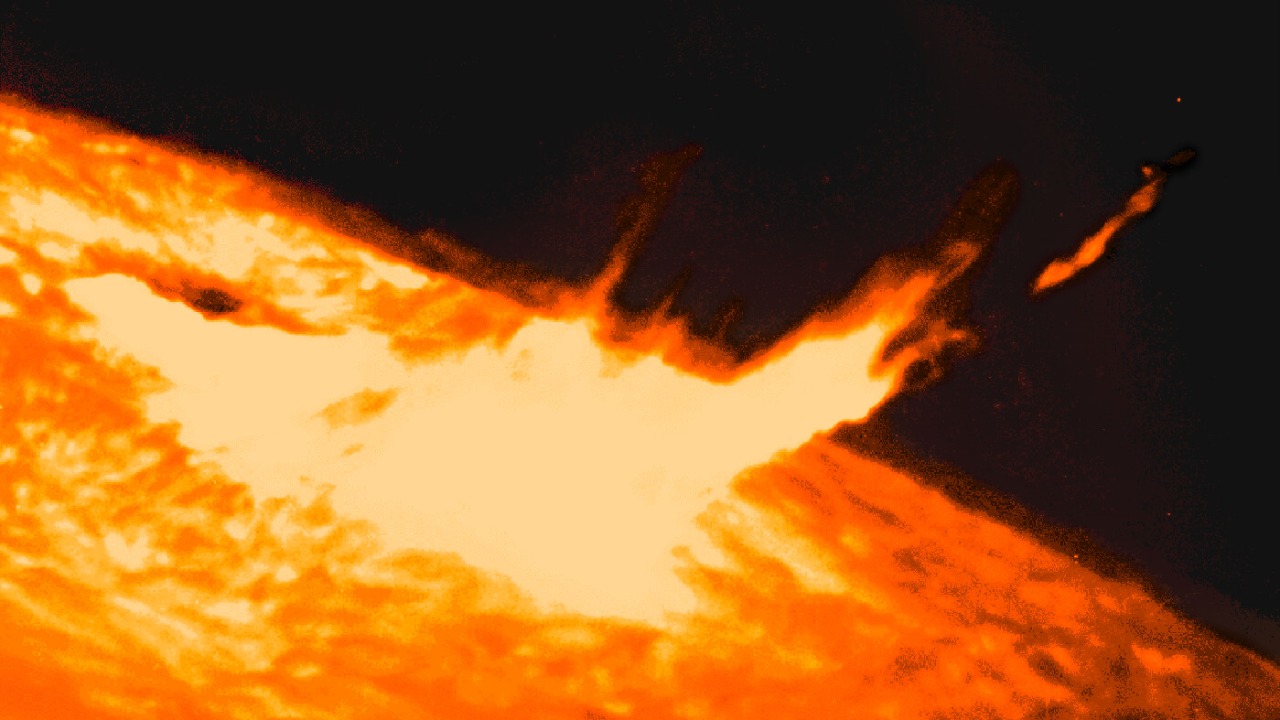

High resolution imagery has captured the drama in real time. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Laboratory recorded one of the key outbursts at 7:33 A.M. EST and classified it as an X-class flare, the most intense category on the standard scale used by space-weather scientists Solar Dynamics Laboratory. A companion explainer notes that the numbers after the “X” provide more information about the type of flares, with the recent fourth flare on 2 February also falling into the X category and adding to the cumulative energy pumped into the surrounding magnetic field numbers after. When I look at that sequence, what stands out is not just the headline power of a single flare but the drumbeat of repeated X-class events, which greatly increases the odds that at least one CME will be aimed close enough to Earth to matter.

From space weather to blackouts: what is really at risk

The phrase “blackout-causing solar flare” is not hyperbole, but the pathway from a burst on the Sun to lights going out on Earth runs through our planet’s magnetic field and power grids. When a CME arrives, it can trigger a geomagnetic storm that induces electric currents in long conductors such as transmission lines and pipelines. A detailed assessment from geophysical experts explains that Today geomagnetic storms can interfere with satellite operations, disrupt GPS and radio communications, and in more extreme cases damage transformers and lead to widespread blackouts across large regions Today. That risk is why agencies and utilities pay close attention to alerts from space-weather centers and sometimes preemptively adjust grid configurations when a strong storm is expected.

In the current case, forecasters are expecting a glancing impact rather than a direct hit, which should limit the severity of any geomagnetic disturbance. A Sun–Earth forecast notes that flare activity is expected to remain Moderate-to-high, with increased chances for M flares at 80% and a smaller but nonzero chance of additional X-class events that could send more material toward Earth around February 5 Sun–Earth forecast. Another update projects that the Arrival of a CME on February 5 is likely to provide only a glancing blow, with Kp 3–4 levels anticipated and a chance for an isolated G1 (minor) geomagnetic storm, a level that can cause weak power grid fluctuations and some impact on satellite operations but is far from a catastrophic scenario Arrival of. In other words, the current “sun burp” is a serious space-weather event that warrants attention, but based on available forecasts it is more likely to cause patchy radio issues and bright auroras than continent-scale blackouts.

More from Morning Overview