Clean energy technologies are colliding with a hard geological limit: the world needs far more copper, lithium, manganese and rare earth elements than conventional mines are currently delivering. At the same time, communities and regulators are pushing back against the pollution, water use and carbon footprint that come with blasting and chemically stripping ore. Into that tension steps an unlikely new workforce for the energy transition, a cast of microbes that can pull metals from rock, waste and even the air with a fraction of the environmental cost.

Instead of sulfuric acid and smokestacks, these “microscopic miners” rely on the same biochemical tricks that let them survive in toxic hot springs and metal-rich soils. If they scale, they could reshape how I think about everything from electric vehicle supply chains to the way we handle discarded smartphones, turning biology into a core tool for securing the metals that clean tech now desperately needs.

The mineral crunch behind the clean energy boom

The global push to replace fossil fuels with wind turbines, solar farms and battery storage is rapidly turning obscure elements into strategic commodities. Analysts tracking the energy transition expect demand for critical minerals such as lithium, copper, manganese and rare earth elements to surge as grids add more renewables and automakers roll out electric models like the Tesla Model 3 and the Ford F‑150 Lightning. One assessment warns that a renewable energy transition will sharply increase the need for these materials and stresses that the world must find ways to ensure the metals are mined responsibly.

Traditional extraction methods are struggling to keep up. New deposits are often lower grade, which means more rock must be crushed and processed to yield the same amount of metal, and that amplifies water use, tailings volumes and greenhouse gas emissions. Communities from Chile’s Atacama Desert to Indonesia’s nickel belt are already wrestling with the social and ecological fallout of this expansion. Against that backdrop, the idea that living organisms could help unlock copper or rare earths from stubborn ores, while also reducing waste and carbon, is no longer a fringe curiosity. It is becoming a serious option in boardrooms and policy circles that are searching for scalable alternatives.

How biomining turns microbes into workers

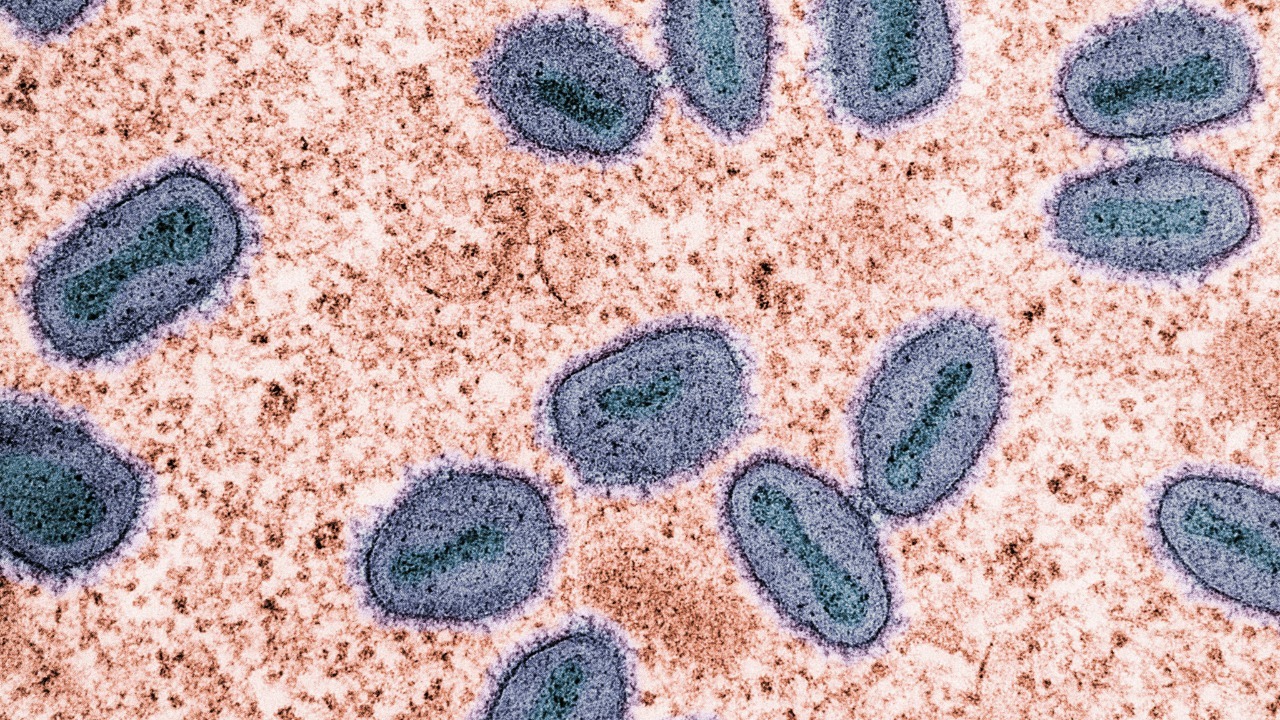

Biomining, sometimes called bioleaching or microbial mining, takes advantage of the way certain bacteria and archaea obtain energy by oxidizing metal sulfides. In industrial setups, these microbes are introduced to crushed ore in heaps or tanks, where their metabolism converts insoluble minerals into soluble forms that can be recovered from solution. Practitioners describe microbes used in microbial mining as specialists in extreme environments, able to tolerate high acidity and metal concentrations that would kill most life, which is exactly what makes them useful for mining.

In one widely discussed technique, operators fill vast tanks with carefully selected microorganisms that leach metals from ore or industrial residues. As the microbes work, the targeted elements move into solution, where they can be separated and concentrated, sometimes by adding reagents that cause the metal-bearing compounds to float to the surface. Descriptions of this approach liken it to a science fiction scene, with microorgaisms in tanks leaching the valuable fraction until it floats to the top. For operators, the appeal is not just novelty. These systems can run at ambient temperatures, use milder chemicals and generate less toxic waste than conventional smelting and acid leaching.

From rare earths to gold: the new microbial toolkit

Researchers are now expanding the biomining toolbox beyond naturally hardy species to engineered strains tailored for specific metals. At Cornell, scientists have focused on a “little bacterium” that can latch onto rare earth elements, which are essential for high performance magnets in wind turbines and electric vehicles. In a recent study, they showed that genetically engineering this bacterium can significantly improve how it binds and separates these elements, a step they argue could boost global economic supply that currently depend heavily on China to process them. That kind of targeted bioengineering hints at a future in which different microbes are matched to different parts of the periodic table.

Other work is revealing just how versatile these organisms can be. One bacterium, Cupriavidus metallidurans, has been found to thrive in highly toxic environments filled with metals such as gold and copper, and its metabolism is so effective that it has been linked to as much as 5% of global gold production in certain contexts. Advocates for microbial mining point to Cupriavidus metallidurans as proof that biology can handle metals that are notoriously difficult and dirty to extract. When I look at that track record, it becomes easier to imagine similar strategies being applied to cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo or nickel laterites in Southeast Asia, where environmental and human rights concerns are acute.

Mapping and engineering the “microbe atlas”

To move from promising case studies to a robust industry, scientists are trying to systematically catalog which microbes can do what. One effort is building a kind of “microbe atlas” that links specific organisms to the critical metals they can help extract. The project’s architects describe how they are collecting and characterizing strains that interact with copper and other strategic elements, with the goal of identifying which ones are most useful for mining critical metals sustainably. For industry, that kind of database could function like a parts catalog, letting engineers pick microbial “components” for different ore bodies and waste streams.

Parallel work is exploring how these organisms can deliver climate benefits alongside metal recovery. A team at Cornell has reported that certain microbes capable of extracting rare earth elements can also capture carbon, and they emphasize that this process can occur in ambient conditions, at low temperature, without harsh chemicals. One researcher, Lee, has highlighted how this dual function could turn biomining sites into modest carbon sinks rather than sources of emissions, especially if powered by renewable energy. The group’s findings suggest that this process might eventually be integrated into broader carbon management strategies, adding another incentive for policymakers to support microbial approaches.

From e‑waste to commercial pilots: where biomining goes next

One of the most immediate frontiers for microbial mining is not deep underground but in the growing mountains of discarded electronics. The increase in e‑waste in recent years is described in technical reviews as a global concern, both because of the toxic components and because of the valuable metals that are currently lost. Researchers working on biohydrometallurgical techniques argue that microbe-based heavy metal remediation can overcome some of the limitations of conventional recycling, using biological processes to pull copper, gold and rare earths from shredded circuit boards and other scrap. They note that in recent decades these methods have been refined to recover heavy metals from, potentially turning a pollution problem into a domestic resource stream for clean technology manufacturers.

Commercial interest is starting to catch up with the science. Last week, the Denver-based company Endolith announced the completion of tests on whether its mix of genetically modified microbes can extract metals in real-world conditions, a milestone that suggests investors are ready to back field trials rather than just lab experiments. Executives at the firm, which is headquartered in Denver, have framed their work as a way to let bacteria serve as “microscopic miners” of the metals we need, and they argue that the biology has been ready for years and that we are just finally paying attention. The company’s recent update on Last week of testing underscores how quickly this field is moving from concept to pilot plants.

More from Morning Overview