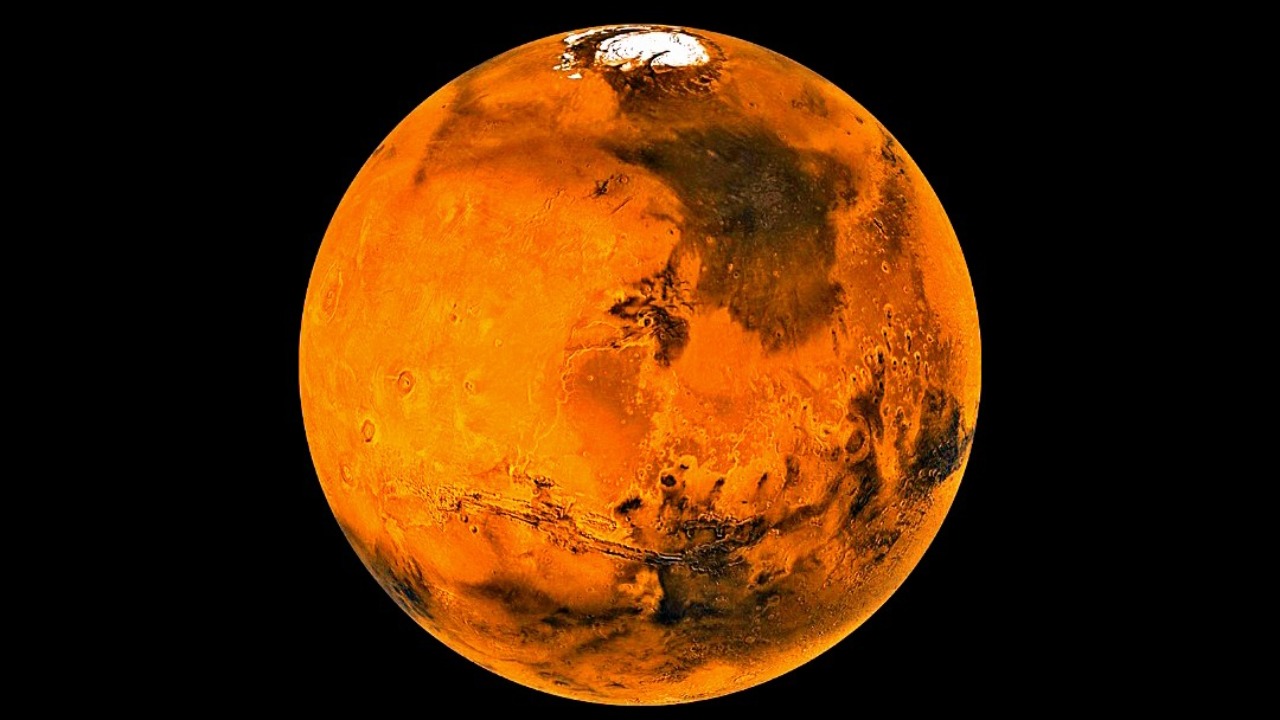

Earth’s ice ages have long been blamed on subtle wobbles in our own orbit, but new research suggests a distant accomplice is quietly helping to set the tempo. Mars, sitting millions of miles away and far smaller than Earth, appears to tug just hard enough on our planet’s path around the Sun to shape a repeating deep-freeze rhythm in the climate record. If that is right, the Red Planet is not just a neighbor in space, it is a hidden player in Earth’s long-term environmental history.

The emerging picture is that tiny gravitational nudges from Mars feed into the same orbital cycles that already govern how sunlight is distributed across Earth’s surface. Over spans of millions of years, those nudges can amplify or damp the conditions that favor sprawling ice sheets, shifting coastlines, and reorganized ocean currents. I find that idea as unsettling as it is elegant: a reminder that Earth’s climate is wired into the broader architecture of the solar system.

From Milankovitch to Mars: updating the ice age playbook

For more than a century, scientists have relied on Milankovitch cycles to explain why ice ages come and go. These cycles, named for the Serbian geophysicist Milutin Milankovitch, describe slow changes in Earth’s orbit and tilt that alter how much solar energy reaches different latitudes and seasons. Variations in eccentricity, obliquity, and precession change how circular or stretched Earth’s path is, how steeply the planet is tilted, and when the Northern Hemisphere leans toward the Sun, all of which affect the contrast between summers and winters and the growth or retreat of ice sheets.

What the new work adds is a sharper look at how other planets modulate those familiar patterns. The same gravitational interactions that generate Milankovitch cycles also mean that Earth’s orbit is never evolving in isolation, it is constantly being nudged by neighboring worlds with similar orbital periods. Researchers now argue that Mars, in particular, is having a bigger effect than many had assumed, because its mass and distance line up in a way that efficiently perturbs Earth’s eccentricity and the timing of its closest approach to the Sun, as highlighted in analyses of these orbital cycles and the broader framework of Milankovitch theory.

The 2.4-million-year rhythm that points to Mars

The most striking clue that Mars is involved comes from a repeating pattern in Earth’s climate that shows up roughly every 2.4 million years. In deep-sea sediments and other geological archives, scientists have traced a long-period cycle in ocean temperatures, ice volume, and carbon storage that does not fit neatly into the classic Milankovitch bands of tens to hundreds of thousands of years. Instead, it appears as a slower metronome, pacing major reorganizations of the climate system and the waxing and waning of ice sheets on multimillion-year horizons.

Recent work argues that this 2.4-million-year signal is the fingerprint of Mars’s gravitational pull subtly reshaping Earth’s orbit. In a series of detailed simulation experiments, researchers removed Mars from the solar system model and watched what happened to Earth’s orbital evolution. Without the Red Planet, the key 2.4-million-year climate cycle that helps pace Earth’s ice ages simply vanished, replaced by a different rhythm that would have produced another pattern of glacial advances and retreats. A companion summary of the work, framed “In A Nutshell,” emphasizes that the 2.4-million-year pacing emerges specifically from long term gravitational interactions between Mars and Earth, a conclusion that rests on the same simulation runs and their sensitivity tests.

How tiny tugs from Mars reshape Earth’s orbit

On human timescales, Mars feels remote and harmless, a small reddish dot that Jan and other skywatchers track in backyard telescopes. Over millions of years, however, its gravity adds up. As Mars and Earth repeatedly line up in their orbits, the slight pull from the smaller planet tweaks Earth’s eccentricity, shifting how circular or elongated our path around the Sun becomes. Those tweaks change the intensity of seasons, especially in the high latitudes where ice sheets either melt away in warm summers or survive to thicken year after year, a process that underpins the classic Milankovitch-style explanation of ice ages.

In the new modeling work, scientists used a high precision Computer code to track how Earth’s orbit would evolve with and without Mars, running the system forward for tens of millions of years. The results show that Mars, despite its small size and distance, significantly influences Earth’s long term climate cycles by affecting the planet’s orbital shape and the timing of its closest approach to the Sun, a conclusion echoed in independent discussions of how Mars and Earth interact. When researchers at the University of California, Riverside, repeated those Computer runs in a separate simulation study, they again found that Without Mars, Earth’s ice age rhythm would change in ways that match the disappearance of the 2.4-million-year pacing.

Oceans, whirlpools, and the deep-time climate machinery

The influence of Mars does not stop at the ice sheets. Earth’s oceans act as a vast flywheel for climate, storing heat and carbon and redistributing energy from the equator to the poles. When orbital cycles shift the pattern of sunlight, the oceans respond by reorganizing currents, stratification, and upwelling. Researchers have linked the 2.4 M megacycle to repeated changes in deep ocean circulation and carbon burial, arguing that Mars Has an Unexpected Influence on Earth, Oceans and Climate, Repeating Every few million years as the gravitational configuration of the inner solar system slowly evolves, a pattern highlighted in work on this 2.4 M cycle.

One vivid way to picture this is to imagine the deep ocean as a slow moving conveyor belt that can speed up, slow down, or even change routes when pushed by orbital forcing. Earlier research suggested that Mars could be creating giant whirlpools deep within our planet’s oceans, vast eddies that form as the gravitational pull Mars exerts on Earth subtly modulates tides and currents over million year intervals. Those giant whirlpools would not be visible from the surface, but they could help mix heat and nutrients in ways that feed back into climate, a possibility that has been explored in reporting on how Mars gravity might shape the oceans. When I look at those findings alongside the new orbital simulations, the picture that emerges is of a coupled system in which Mars’s tugs ripple from the shape of Earth’s orbit all the way down to the abyssal seafloor.

Why a Martian climate “knob” matters for life on Earth

For climate scientists, the idea that Mars Can Actually Trigger Ice Ages on Earth Despite Being Millions of Miles Away is more than a curiosity, it is a test of how well we understand the full chain of cause and effect in the climate system. If a distant planet can help set a 2.4 m rhythm in ice ages, then any attempt to reconstruct past climates or forecast far future conditions has to account for that external forcing. Researchers working with New simulations suggest that Mars may help set the timing of Earth’s ice ages by tuning this long period cycle, a conclusion drawn from Computer runs that allowed the experts to isolate Mars’s contribution and identify its signature in deep time climate records, as described in analyses of how Mars may pace glaciations. That work dovetails with broader coverage of how Earth’s ice ages are shaped by tiny tugs from Mars, a reminder that even small gravitational forces can matter when integrated over millions of years, as highlighted in discussions of Earths freezing history.

More from Morning Overview