Mars has always felt like a distant neighbor, reachable only after a long, risky cruise through deep space. Now engineers inside NASA are sketching a very different future, one where a nuclear powered spacecraft could sprint to the red planet in roughly a month and a half instead of most of a year. The promise is simple but staggering: cut the trip to about 45 days, shrink the danger window for astronauts, and turn Mars from a once in a generation expedition into a more routine destination.

Behind that promise sits a cluster of nuclear rocket concepts that are moving from whiteboard to funded studies and early hardware. I see a through line connecting NASA’s experimental propulsion work, the Pentagon’s interest in fast maneuvering spacecraft, and a parallel push to put nuclear reactors on the Moon, all of it pointing toward a nuclear powered infrastructure for the inner solar system.

Why 45 days to Mars changes everything

The headline number, a sprint to Mars in about 45 days, is not just a flex of engineering ambition, it is a direct response to the brutal realities of human physiology and radiation. Traditional chemical rockets leave crews exposed to cosmic rays and solar storms for many months, which is why cutting the journey by roughly sixfold would make the red planet “innumerably safer for humans,” as one analysis of the NASA concept puts it. Shorter exposure also eases concerns about microgravity induced bone loss and muscle wasting, which only get worse on the long outbound and return legs of a conventional mission.

On current trajectories, a crewed Mars expedition can stretch toward three years, with long coasting arcs and tight launch windows that dictate when Earth and Mars line up. Reporting on NASA’s planning notes that, based on conventional propulsion technology, a mission could last “up to three years,” with crews spending long stretches in deep space before even reaching Mars orbit, a reality that has shaped every serious architecture study so far Based on conventional. If nuclear propulsion can compress that timeline to a fast transfer, it does more than save time, it changes how mission designers think about supplies, abort options, and psychological strain on astronauts who would no longer be signing up for a multi year exile.

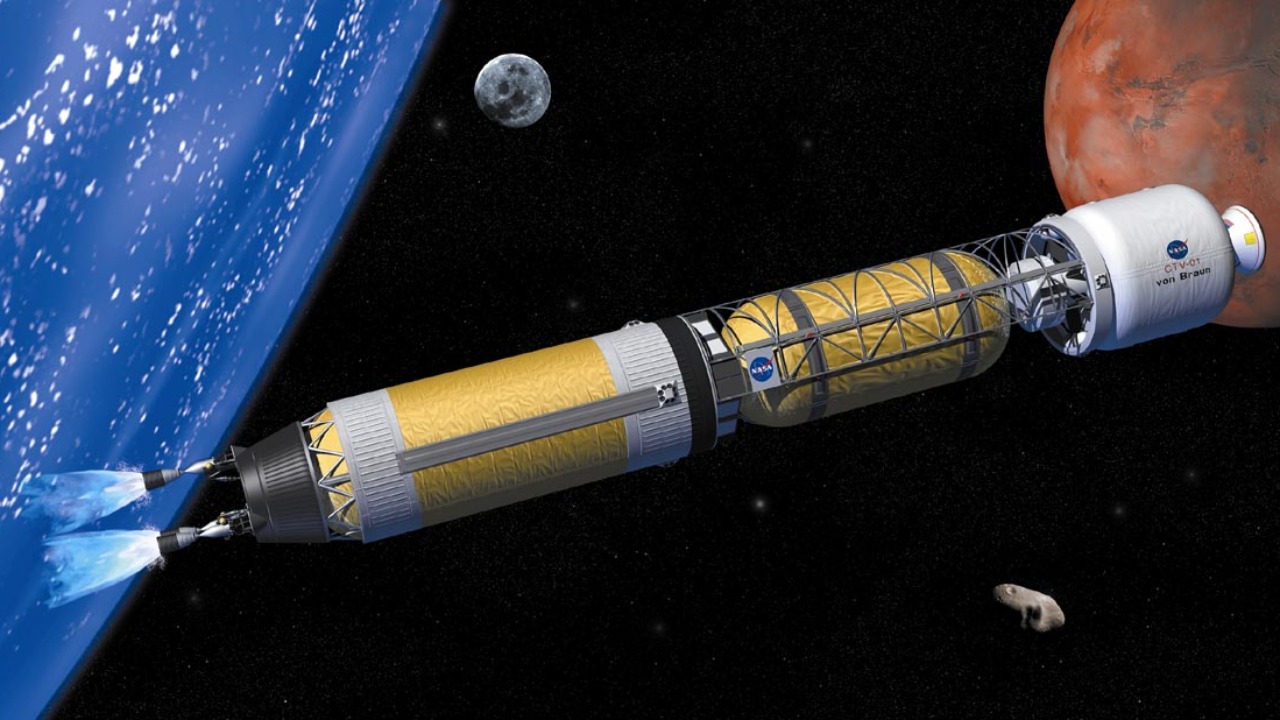

Inside NASA’s nuclear propulsion concepts

NASA’s current roadmap leans on a hybrid approach that marries nuclear thermal propulsion, which heats propellant with a reactor, and nuclear electric propulsion, which uses a reactor to power high efficiency electric thrusters. In one study selected for Phase I development, engineers describe a bimodal design that uses a nuclear thermal stage for the initial push out of Earth’s gravity well, then switches to nuclear electric engines for the long acceleration and braking phases, a combination that could enable a roughly 45 day transit to Mars and “revolutionize” deep space exploration bimodal design. The key is using the reactor twice, first as a heat source and then as a power plant, squeezing maximum performance out of a single nuclear core.

Shorter travel times are not just a convenience, they are described inside NASA’s own advanced concepts work as “vital” for the future of human space exploration, both for science and for any eventual settlement effort. The same internal framing emphasizes that nuclear propulsion could cut existing travel estimates sixfold compared with chemical rockets, a leap that would turn Mars logistics into something closer to a long duration airline route than a one off expedition shorter travel times. That is why these Phase studies are not just academic exercises, they are being treated as potential cornerstones for how the agency might move people and cargo around the inner solar system in the 2030s and beyond.

From paper studies to hardware tests

Concept art and performance charts only matter if they lead to real engines, and here the story gets more complicated. On the one hand, there is a clear push to test nuclear propulsion hardware in space, with NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, teaming up on a nuclear thermal rocket program known as the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations, or DRACO. The partners have publicly targeted an in orbit demonstration by early 2026, with program updates describing a flight that would carry a nuclear thermal stage into space to validate its performance and safety systems DRACO flight. Planetary scientist Alan Stern has already called the planned test “game changing,” highlighting that NASA and DARPA are preparing to fly the first nuclear rocket in Earth orbit and that They are planning an in space demonstration that could validate the core technology for future Mars missions They are planning.

At the same time, the program has faced political and budget turbulence. A DARPA official has acknowledged that The DRACO project, formally titled the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations, was canceled as a space nuclear propulsion effort after funding cuts tied to President Trump’s budget decisions, a move that raised the question, “Why did NASA’s nuclear rocket program get grounded under Trump’s budget cuts?” and underscored how vulnerable long term propulsion work can be to shifting priorities Why did NASA’s. Public budget documentation around DRACO also cited reductions in unspecified advanced space propulsion projects, a signal that Some analysts interpreted as a warning sign for the broader nuclear propulsion portfolio and its dependence on steady political support Some analysts.

DARPA, ground tests, and the private nuclear push

Even with those headwinds, the technical work has not stopped. In social media updates shared with spaceflight communities, NASA and DARPA are described as beginning ground tests of a nuclear powered spacecraft that could reach Mars in 45 days, with posts highlighting that NASA, in partnership with DARPA, has started exercising hardware that could underpin future fast transfer missions to Mars and beyond NASA tests. Those tests are framed not just as a Mars play but as part of a broader “DeepSpaceTech” effort to give the United States agile, high performance propulsion for cislunar operations and deep space logistics.

Alongside the government programs, a new generation of companies is trying to commercialize nuclear propulsion. One effort backed by Nuclear space power advocates and NASA support has outlined a nuclear electric propulsion system that could fly humans to Mars in just 45 days, with the company SpaceNukes describing how its reactor and thruster package could cut existing travel estimates sixfold compared with chemical systems Nuclear electric. In a widely shared explainer video, posted in Apr and viewed by hundreds of thousands of space enthusiasts, commentators walk through how such a reactor powered spacecraft could accelerate for half the journey and decelerate for the other half, turning the old Hohmann transfer orbit into something closer to a powered sprint across the inner solar system Apr explainer.

The Moon reactor that makes Mars possible

There is another nuclear story unfolding in parallel that, in my view, is just as important for Mars as the rockets themselves. Earlier this month, the Department of Energy and NASA renewed a partnership to put a nuclear reactor on the Moon, with officials describing a plan to deploy a lunar surface reactor by 2030 that could provide continuous power through the two week long lunar night and support everything from habitats to resource extraction Department of Energy. The agreement, reported by Taylor Mitchell in Jan and described in local coverage as a major boost for Huntsville area space work, underscores how seriously NASA is taking nuclear power as a backbone for its long term exploration plans, not just as a propulsion gimmick.

More from Morning Overview