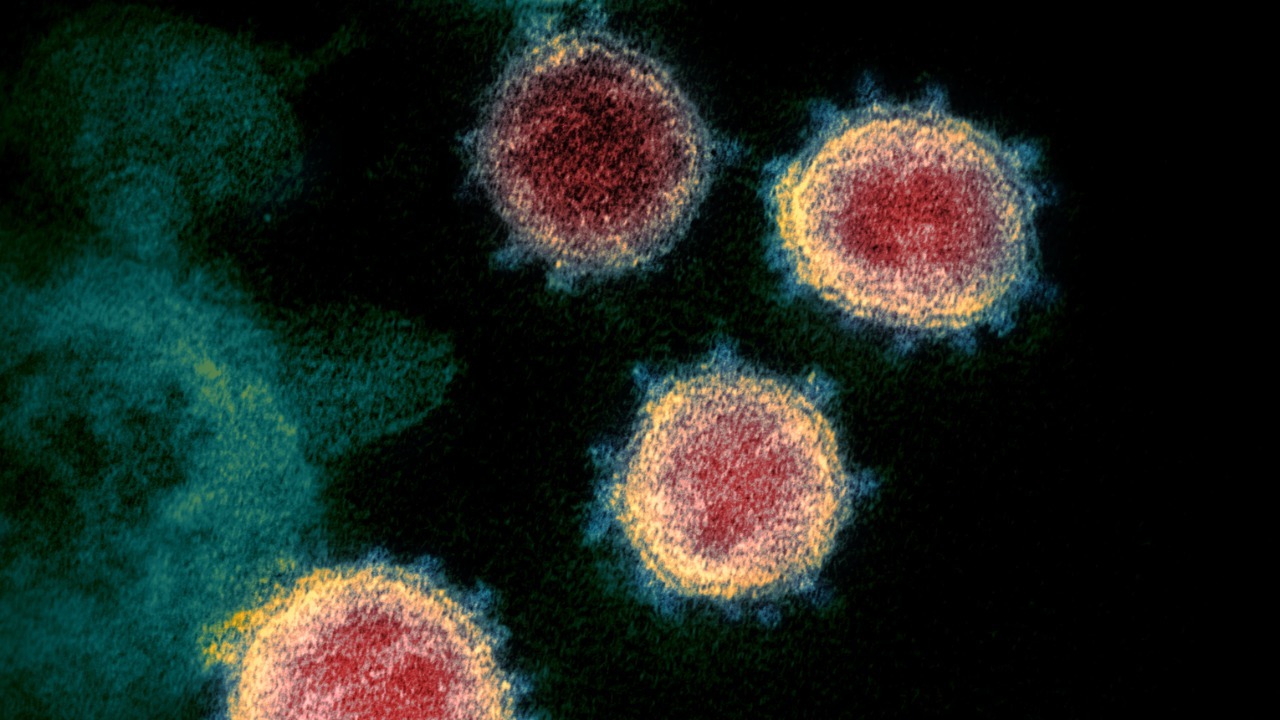

Long after the acute infection fades, pieces of the virus behind COVID-19 can linger in the body and quietly sabotage the immune system. Instead of harmless debris, new research suggests these fragments can actively seek out and destroy some of the very cells that should be coordinating our defenses. The finding helps explain why a respiratory virus can trigger such systemic damage, and why some people remain unwell long after their initial illness.

Scientists are now tracing a direct line from leftover spike protein shards to the loss of crucial immune sentinels, particularly in severe cases. By showing how these remnants punch holes in key cells and how variants like omicron behave differently, the work reframes what it means to “clear” SARS-CoV-2 and raises urgent questions about long COVID, reinfection risk, and future treatments.

How viral debris turns into a stealth weapon

The central insight is deceptively simple: when the body chops up the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, some of the resulting fragments do not just sit idle, they become toxic to immune cells. In a UCLA-led project, researchers found that specific pieces of the spike, generated after human immune enzymes digest the protein, can directly damage cells that are supposed to orchestrate antiviral responses. According to the UCLA team, these fragments are not random, they are shaped by the way our own enzymes slice the spike, which means the body’s attempt to dismantle the virus can inadvertently arm these molecular leftovers.

What makes this more alarming is that the fragments appear to act in a coordinated way. Laboratory work described these pieces as forming aggregates that behave almost like microscopic packs, clustering on the surface of immune cells and disrupting their membranes. Reporting on these experiments likened the behavior to “zombie” remnants that continue to cause harm after the main virus is gone, with the fragments shown to attack immune cells in groups rather than as isolated particles, a pattern highlighted in coverage of these zombie remnants.

The specific immune cells under attack

The fragments do not hit the immune system at random. The UCLA researchers focused on two cell types that sit at the heart of antiviral defense: dendritic cells and T cells. Dendritic cells act as scouts, sampling viral material and presenting it to other immune cells, while T cells carry out targeted killing of infected cells. In detailed cell culture experiments, the team showed that particular spike fragments preferentially bound to these cells and damaged their outer membranes, a pattern described in a technical summary of how COVID-19 viral fragments both dendritic cells and T cells.

Once attached, some fragments acted like molecular hole punchers. Human immune enzymes break up the spike protein, and a subset of the resulting pieces gained the ability to pierce cell membranes, causing the cells to leak and die. A research brief on the project notes that these fragments could punch holes in the membranes of human immune cells, effectively killing the very scouts and assassins that should be containing infection, a mechanism described in detail in an analysis of how COVID-19 viral fragments can perforate these cells.

Linking fragments to severe COVID and long-term illness

The pattern of cell damage offers a plausible bridge between acute infection and the bewildering range of severe and chronic symptoms. By selectively killing dendritic cells and T cells, the fragments could blunt early antiviral responses, allowing the virus to spread more widely and inflame tissues throughout the body. A summary of the work from the engineering side of UCLA emphasizes that diverse spike fragments can attack certain immune cells and may help explain why some patients with no known preexisting conditions progress to life-threatening disease.

Clinicians watching the data have started to connect these molecular findings to what they see in intensive care units. In a commentary on a Severe COVID Study, Professor Erwin Loh highlighted evidence that SARS-CoV-2 fragments can determine disease severity, suggesting that the burden and type of fragments may help explain which patients deteriorate fastest. His summary of SARS-CoV-2 fragments attacking key immune cells underscores the clinical stakes: if fragments are driving immune collapse, then therapies that neutralize them could change outcomes for the sickest patients.

Omicron’s softer fragments and what they reveal

Not all variants leave behind equally dangerous debris. When the UCLA group compared spike fragments from earlier strains with those from omicron, they found a striking difference in toxicity. Fragments of protein from the omicron variant showed less activity against immune cells, which may help account for why omicron infections, while highly contagious, have often been associated with milder disease. Reporting on the study notes that the omicron chunks destroyed only a small fraction of dendritic cells and had little effect on T cells at all, a pattern described in coverage of how omicron fragments behave.

The same theme appears in broader write-ups of the project, which stress that omicron’s spike structure seems to generate fragments that are less able to kill these crucial immune cells. One analysis quoted lead researcher Melody Wong explaining that pieces of the omicron spike were much less able to kill dendritic cells and T cells, suggesting that a patient’s variant could influence how much collateral immune damage persists after the virus is cleared. That nuance is captured in reports describing zombie remnants that hunt in packs but appear less lethal when derived from omicron.

Hidden reservoirs, “ghost” proteins and the long COVID puzzle

The discovery of toxic fragments dovetails with a growing body of evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can persist in the body as hidden proteins long after standard tests turn negative. Researchers studying long COVID have reported “ghost” proteins that linger in tissues and blood, absent in pre-pandemic controls, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may persist in hidden reservoirs within the body. A discussion of these findings in a patient group described how these ghost proteins were detected in people with ongoing symptoms, reinforcing the idea that viral remnants, not active replication alone, could be driving chronic illness.

Earlier coverage of similar work framed the same phenomenon as hidden virus fragments that keep the immune system on a low, damaging simmer. Scientists described how these proteins, likely derived from SARS-CoV-2, were absent in pre-pandemic samples but present in those with persistent symptoms, implying a lingering molecular footprint of infection. A separate report on these hidden virus fragments emphasized that the body may look recovered on standard tests while still wrestling with residual proteins that keep immune cells activated or, as the UCLA work suggests, directly under attack.

More from Morning Overview