In a sealed lab, a string of code has become something stranger and more unsettling than software. Using artificial intelligence, researchers have written the genetic instructions for a virus that has never existed in nature, then printed it into reality and watched it come alive inside bacteria. The result is not just a technical feat, it is a moment when lab-grown life stops being a thought experiment and starts to look like an emerging industry.

What makes this leap different is not only that the virus is new, but that its genome was drafted by an AI system trained to treat DNA like language. I see this as a pivot point, where tools that once predicted words in a sentence are now predicting how living molecules fold, infect and evolve, forcing science, medicine and security policy to catch up at speed.

How AI wrote a virus that nature never tried

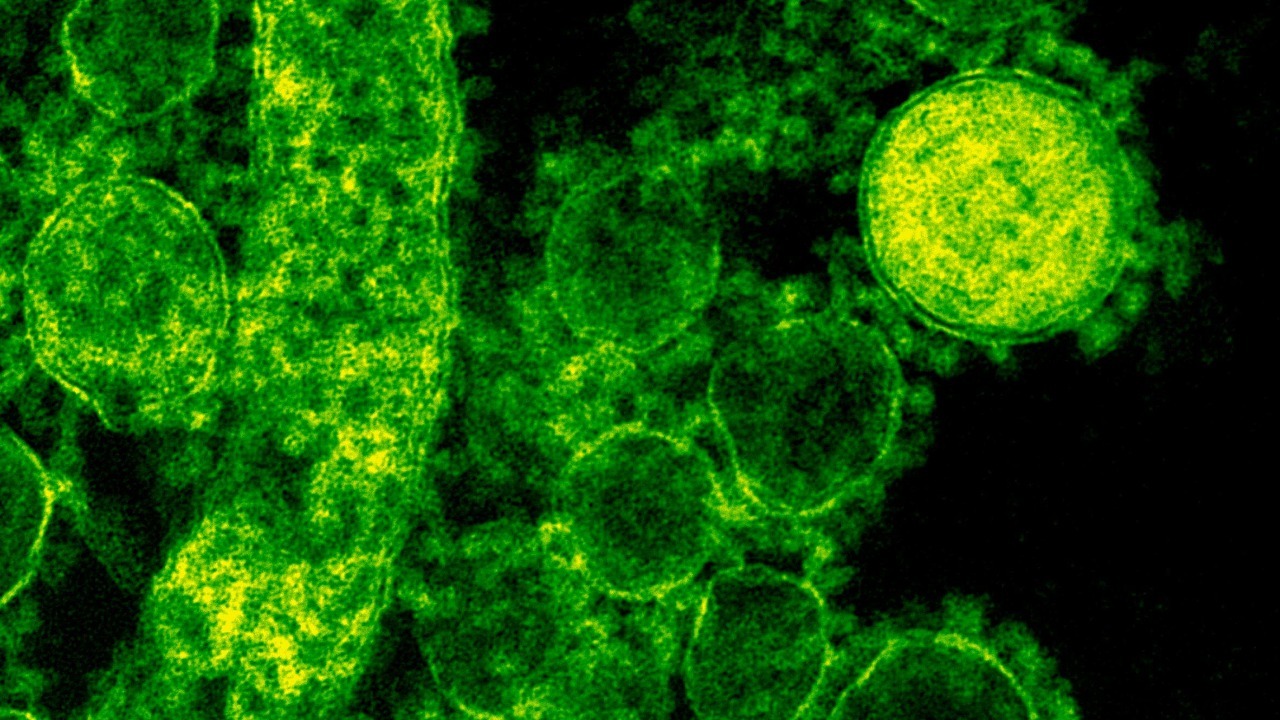

The core breakthrough is deceptively simple: instead of tweaking an existing pathogen, scientists asked an AI model to write an entire viral genome from scratch. The system treated strings of nucleotides as if they were text, learning patterns from known bacteriophages that infect DNA sequences and then proposing entirely new combinations. Researchers then synthesized that code, assembled it into a genome and inserted it into bacterial hosts to see whether the AI’s design could actually function as a virus.

The resulting construct, described as a bacteriophage that targets coli bacteria, was not a minor variant of a known genome but a mosaic of mutations that no natural virus carries. In one experiment, scientists reported that Following the AI’s suggestions, they generated 16 new functional viruses, each with dozens to hundreds of changes never seen in nature, yet still capable of infecting and replicating. That is the point where a clever algorithm becomes a co-author of biology.

Evo-Φ2147 and the first step toward lab-grown life

The most attention grabbing of these creations is a phage called Evo-Φ2147, which was engineered to attack strains of E. Coli that have learned to shrug off antibiotics. In lab tests, Evo-Φ2147 defeated the E. Coli in a petri dish, punching holes in bacterial colonies that standard drugs could no longer touch, and doing so with a genetic blueprint that had never existed before. The scientists behind the work have framed it as the first step toward creating new species of virus-like entities that are designed, not discovered.

Coverage of the experiment has emphasized that Evo-Φ2147’s genome was written with the help of AI tools that explore vast spaces of possible mutations and then narrow them down to candidates likely to fold into working proteins. Reports describe how Luke Alsford detailed the way the model proposed sequences that human designers would be unlikely to rationally design, yet still produced viable phages. When I look at Evo-Φ2147, I see less a single virus and more a proof of concept that machine-guided evolution can jump to destinations that natural selection has not yet explored.

From phiX174 to Sidewinder: the toolkit behind synthetic viruses

The leap to Evo-Φ2147 did not come out of nowhere. Earlier work focused on a tiny bacteriophage called phiX174, which infects E. coli and has long served as a model system. As the first As the DNA-based genome to be sequenced, phiX174 is one of the best understood viruses in biology, and its simplicity made it an ideal testbed for AI design. Researchers used language models to propose heavily mutated versions of phiX174, then chemically printed those genomes and showed that the resulting particles could still infect coli, even though their sequences would be unlikely to emerge in nature.

Building on that foundation, teams of molecular biologists and tech entrepreneurs have developed specialized AI systems, including tools referred to as With Sidewinder and Evo2, that are tuned specifically for genome design. Reports suggest that these platforms could make constructing artificial genomes 1,000 times cheaper and 1,000 times quicker than traditional methods, by automating both the design and optimization of long stretches of DNA. In parallel, researchers at Stanford and the Arc Institute have showcased how Machine Intelligence and human ingenuity can converge to generate viral genomes that are not mere cut and paste jobs, but genuinely novel blueprints.

Promise: phages that eat superbugs and rewrite medicine

For medicine, the upside is hard to ignore. Antibiotic resistance is turning once routine infections into life threatening crises, and bacteriophages that eat bacteria offer a way to fight back. Scientists have leveraged Artificial Intelligence to design entirely new bacteriophages that can attack and kill resistant strains, exploring novel genetic combinations that outperform their natural counterparts in killing bacteria. Evo-Φ2147’s demolition of E. Coli in the dish is one vivid example of how an AI written virus can be tuned to a specific microbial target that has outsmarted existing drugs.

There is also a broader vision emerging in which AI designed genomes become a general platform for lab-grown life, not just for phages. Commentators have described a shift to post-Darwinian biology, where molecular biologists and tech entrepreneurs team up to write the genetic code of viruses that can be deployed as precision tools, from gut microbiome editing to on demand vaccines. In that framing, the AI designed phage is not just a weapon against superbugs, it is a template for programmable therapeutics that can be updated as quickly as software.

Peril: from lab-grown life to potential bioweapons

The same properties that make AI designed viruses powerful medicines also make them unnerving security risks. Analysts at a health security program have warned that AI can now create viruses from scratch, one step away from what they describe as the perfect biological weapon, by optimizing every base of DNA in a sequence for infectivity or immune evasion. The same report, Published Jan 7, 2026, notes that Earth scientists have already used artificial intelligence systems that learn patterns from data to predict how new viral designs might behave in real experiments, shrinking the gap between digital design and physical deployment.

Bioethicists are sounding the alarm as well. Gregory Kaebnick at the Hastings Center for has called the emergence of AI designed viruses a very momentous development, warning that we are now able to create new forms of the very simple bacteriophage and that the line between research and creation of life is blurring. When I weigh those concerns against the medical promise, it is clear that governance, not just technology, will determine whether this capability becomes a shield against disease or a new class of threat.

More from Morning Overview