The creature locals now call “Godzillus” did not roar out of a movie screen but out of Ordovician rock, lifted piece by piece from a Kentucky hillside by a determined hobbyist. What began as a routine fossil hunt turned into the unearthing of a roughly 7‑foot, 150‑pound slab of mystery that has resisted every attempt at easy classification and still teases scientists with the possibility of something entirely new.

More than a decade after that dig, the fossil remains a scientific cliffhanger, a 450‑million‑year puzzle that has drawn in professional paleontologists, inspired online sleuths, and kept one amateur collector returning to the same outcrop in search of answers. I see in this story not just a strange specimen, but a case study in how science handles the unknown when the rock refuses to give up its secrets.

The day a hobbyist hit something too big to ignore

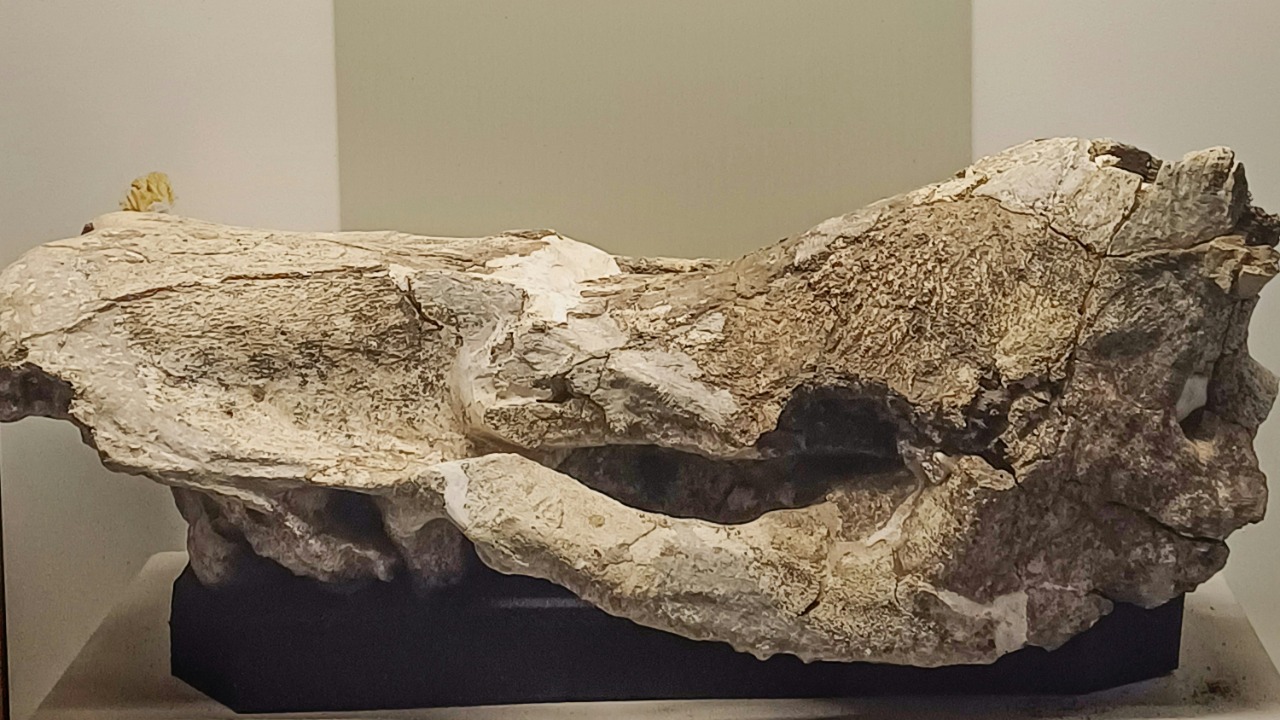

The story of Godzillus starts with a man on his hands and knees in northern Kentucky, scanning weathered shale for the usual small trilobites and brachiopods. Instead, Uncovered in 2011 by amateur fossil hunter Ron Fine, then 43, of Dayton, Ohio, the find quickly proved to be far beyond the pocket‑sized souvenirs most collectors carry home, eventually weighing in at about 70‑kilogram, or roughly 150 pounds, once the main pieces were freed from the hillside and reassembled in his garage, a scale that immediately set it apart from the surrounding fauna and earned it a place among strange phenomena that stump experts. Fine’s background was not in academia but in persistent fieldwork, the kind of weekend labor that involves hauling chisels, sleds, and tarps into road cuts and creek beds until something unusual finally turns up.

When he began to expose the fossil, Fine realized he was not dealing with a single shell or bone but a sprawling, multilobed mass that extended far beyond the first nodule he tapped. Later measurements described a structure about 1 meter wide and 2 meters long, roughly 3′3″ by 6′6″, a footprint that forced him to excavate in sections and then puzzle the slabs back together at home, a process that, as one reconstruction account put it, began with an oddly textured nodule and ended with a giant, quilt‑like surface that looked nothing like the standard Ordovician catalog, a sequence detailed in an illustrated reconstruction. By the time he finished, Fine had effectively pulled a 7‑foot enigma out of the Kope Formation, and the specimen’s sheer size and texture convinced him it needed professional scrutiny.

From backyard project to 450‑Million‑Year mystery

Once Fine brought the fossil to the attention of specialists, the story shifted from a backyard project to a formal scientific puzzle rooted in deep time. Paleontologists examining the slab agreed that the rock dated to roughly 450-Million-Year age, placing it in the Ordovician seas that once covered what is now Kentucky, a conclusion tied to the well‑studied Kope Formation near Covington, where an Amateur Paleontologist Discovers specimen was reported. That timeframe alone is not unusual for the region, but the fossil’s architecture was, and early descriptions leaned on phrases like Million, Year, Old Monster to capture how outsized and perplexing it appeared compared with the typical invertebrate shells that litter the same beds, language that surfaced again when News Staff summarized the find for a broader audience.

Local coverage in DAYTON framed the discovery as a record fossil find by a hometown enthusiast, emphasizing that the specimen was roughly 450 m years old and still defied identification even after experts weighed in, a reminder that not every spectacular rock yields a neat label, as highlighted in a What style feature that invited readers to guess at its nature. For Fine, the transition from private curiosity to public mystery meant handing his prize over to labs and museums, where thin sections, photographs, and comparative collections could be brought to bear, but it also meant accepting that the answer might be “we do not know yet,” even after the specimen had been measured, mapped, and debated.

Why scientists still cannot agree what Godzillus was

What makes Godzillus so stubborn is not a lack of data but a lack of clear analogues. When specialists first examined the fossil, they struggled to decide whether it represented a single organism, a colony, or even a disturbed sedimentary structure, and that uncertainty persists in the technical discussions that followed. Some researchers suggested it might be a large algal mat or microbial growth, others floated comparisons to soft‑bodied invertebrates, and at least one analysis raised the possibility of a colonial animal such as a bryozoan or polyp, a range of interpretations that surfaced in the same local report that asked readers in DAYTON, “What do you think about this find?” and noted that it might be a colony or polyp according to one Dattilo assessment. The problem is that the fossil’s multilobed, “goose flesh” surface does not match any textbook example cleanly enough to close the case.

Fine himself has been candid about the ambiguity, telling reporters that “We just don’t know yet exactly what it is,” and adding that scientists do not even agree whether it is a plant or an animal or what kingdom of life it should be assigned to, a level of uncertainty that was underscored when he spoke to one outlet that described the specimen as a mystery cactus‑like fossil and quoted him on the lack of consensus, as captured in an Apr feature. Another summary of the debate noted that scientists say the fossil is 150-pound and that Fine discovered it in northern Kentucky and gave it its name, while also stressing that experts are still trying to figure out what the structure used to be, a sentiment echoed by Experts and enthusiasts who have followed the case. In that sense, Godzillus functions as a live demonstration of how paleontology often operates at the edge of analogy, where even well preserved fossils can resist tidy classification.

How “Godzillus” got its name and a life of its own

Long before the scientific verdict, the fossil had already acquired a personality. Fine dubbed the big multilobed, “goose flesh” textured fossil “Godzillus,” explaining that he picked that name to make it sound more scientific while also nodding to its monstrous scale, a choice that stuck in subsequent coverage and helped the specimen stand out in a crowded field of Ordovician curiosities, as one analysis of the case noted when describing how Fine coined the term. The playful label did more than brand the rock, it gave locals and readers a shorthand for a complex scientific puzzle, turning an abstract “enigmatic fossil” into a character that could be followed over time.

That nickname also helped propel the fossil into broader popular culture, where it has been cataloged as a tentative 450-million-year specimen discovered in a rock layer near Covington, Kentuck, with some summaries noting that one interpretation is that it might be a fossilized mat of algae, a possibility that underscores how even a monster name can cloak something as humble as microbial growth, as seen in a concise Godzillus entry. In online forums and listicles, the fossil now appears alongside other unsolved natural mysteries, its pop‑culture moniker ensuring that even readers who cannot parse Ordovician stratigraphy can still recognize the story of the Kentucky “beast” that refuses to reveal what kind of life it once hosted.

More from Morning Overview