The James Webb Space Telescope is turning distant exoplanets from anonymous dots of light into worlds with weather, chemistry, and sometimes even hints of clouds. By dissecting the faint starlight that filters through alien skies, it is already reshaping what astronomers thought was possible to learn about planets orbiting other stars. I see the early results as a preview of a much more radical shift to come, in which atmospheric fingerprints could reveal how common habitable environments, and perhaps even life, really are in our galaxy.

From blurry dots to resolved alien skies

For most of the past three decades, exoplanets were statistics more than places, cataloged by their masses and orbits rather than their climates. Webb’s infrared vision is changing that by turning transit observations into detailed atmospheric spectra, letting researchers separate starlight from the subtle absorption features of molecules high above an exoplanet’s surface. Instead of asking only where planets are, astronomers can now ask what their skies are made of and how those atmospheres evolve under extreme conditions.

That shift is already visible in the way teams talk about “characterizing” exoplanets rather than simply detecting them, a change driven by Webb’s ability to pick out narrow spectral lines that older observatories could not reliably see. In practice, that means the telescope can distinguish between a hydrogen-rich envelope, a heavier mix of water and carbon dioxide, or a stripped, airless rock, all from tiny variations in the depth of a transit at different wavelengths. The result is a new kind of planetary census that treats atmospheres as primary data rather than an afterthought.

A lava world that should not have an atmosphere

One of the clearest examples of Webb’s disruptive power is its scrutiny of ultra-hot rocky planets that orbit so close to their stars that their surfaces are expected to be molten. A standout case is the lava planet TOI‑561 b, a world so intensely irradiated that many models predicted any primordial gases would have been blasted away long ago. Yet Webb’s measurements have revealed signs of an atmosphere clinging to this extreme environment, a finding that forces a rethink of how such planets form and how long their envelopes can survive under relentless stellar bombardment, as highlighted in reporting on the atmosphere on lava planet TOI‑561 b.

For a planet like TOI‑561 b, the presence of any detectable gases raises difficult questions about whether we are seeing a remnant of its original composition or a secondary atmosphere generated by volcanic outgassing from a magma ocean. Webb’s spectrum lets researchers test those scenarios by comparing the relative strengths of different molecular features, which in turn trace the balance between lighter elements and heavier volatiles. I see this as more than a curiosity about one exotic world; it is a stress test of atmospheric escape theories that also matter for understanding how Earth-like planets hold on to their air over billions of years.

TRAPPIST‑1 and the search for stripped or sheltered Earths

If lava planets probe the outer edge of survivable atmospheres, the TRAPPIST‑1 system sits at the center of the habitability conversation. Its seven Earth-sized planets, several in the temperate zone, are prime targets for Webb because they offer a rare chance to compare multiple rocky worlds around the same cool star. Early Webb observations of TRAPPIST‑1 d have already narrowed the range of possible atmospheres, showing what the planet does not have and hinting at how harsh the stellar environment may be for retaining thick envelopes, according to detailed results on how Webb narrows atmospheric possibilities for TRAPPIST‑1 d.

Those findings suggest that at least some TRAPPIST‑1 planets may lack the kind of puffy hydrogen-dominated atmospheres that would make them more like mini-Neptunes than true terrestrial worlds. Instead, the data are more consistent with either compact, heavier atmospheres or nearly bare rocks, outcomes shaped by the star’s intense flares and high-energy radiation. As Webb continues to observe the system, I expect the comparison between different TRAPPIST‑1 planets to become a laboratory for understanding how red dwarf stars sculpt the fates of potentially habitable planets, from those that keep dense, protective air to those that are stripped nearly clean.

Clouds, hazes, and a “never seen” atmospheric chemistry

Webb is not only confirming expectations; it is also uncovering atmospheric combinations that do not fit neatly into existing categories. One recent analysis describes a new exoplanet atmosphere that researchers characterize as “never seen” before, a mix of molecules and thermal structure that diverges from the standard templates used to interpret spectra. The observations reveal a complex interplay of gases and likely clouds or hazes that reshape the planet’s energy balance, as detailed in the report on a new JWST exoplanet atmosphere never seen.

What stands out to me is how quickly Webb is forcing modelers to expand their toolkits. Instead of tweaking a few parameters on familiar hot Jupiter or warm Neptune scenarios, teams are now building more flexible frameworks that can accommodate unexpected chemistry and layered aerosols. That shift matters because clouds and hazes can mute or mimic key molecular features, which in turn affects how confidently we can identify water, methane, or other potential biosignature gases on smaller, cooler planets. Every “weird” atmosphere Webb uncovers on a giant world becomes a training ground for interpreting subtler signals on Earth-sized targets.

From water vapor to detailed weather on giant exoplanets

While rocky planets capture the headlines, Webb’s most detailed atmospheric work so far has come from larger gas and ice giants, where thick envelopes produce strong spectral features. In one flagship observation, the telescope delivered a high-precision transmission spectrum that mapped out multiple molecular species, temperature gradients, and even hints of cloud layers in a single exoplanet’s sky. The level of detail in that dataset, described in a release on how Webb reveals an exoplanet atmosphere in striking detail, effectively turned a distant world into a case study in alien meteorology.

Those spectra do more than list ingredients; they let researchers infer circulation patterns, day–night temperature contrasts, and how efficiently heat is transported around the planet. When combined with time-resolved measurements, Webb can even watch how clouds form and dissipate as the planet orbits, offering a dynamic view that was out of reach for previous missions. I see these giant planets as the proving ground where techniques for extracting three-dimensional weather maps are being refined, techniques that will eventually be pushed toward smaller, cooler worlds where the stakes for habitability are higher.

How Webb actually reads an alien atmosphere

Behind every headline about a surprising atmosphere is a demanding chain of observations and analysis that turns tiny changes in starlight into chemical fingerprints. Webb typically uses transit spectroscopy, watching a planet pass in front of its star and measuring how the depth of the transit varies with wavelength as gases absorb specific colors of light. A detailed breakdown of this process, including how instruments separate planetary signals from stellar noise and instrumental systematics, is laid out in an explainer on JWST exoplanet atmosphere measurements.

In practice, the challenge is not just detecting a feature but proving it is real and not an artifact of stellar activity or data reduction choices. That is why teams cross-check results with multiple instruments and independent pipelines, and why they are cautious about claiming detections of molecules that could be interpreted as signs of life. From my perspective, the rigor of this process is a feature, not a bug, because it builds the credibility needed for the far more contentious claims that may come when Webb or its successors see patterns consistent with biological activity.

Hazy worlds and the hunt for biosignatures

The most tantalizing promise of Webb’s atmospheric work is the possibility of detecting biosignatures, combinations of gases that are hard to explain without some form of life. One emerging line of research argues that hazy exoplanets, which were once seen as frustratingly opaque, might actually be among the best places to look for such signals. Detailed modeling shows that certain photochemical hazes can coexist with detectable amounts of oxygen, methane, or other disequilibrium gases, making them promising targets for Webb’s infrared instruments, as explored in a technical discussion of how JWST could expose alien biosignatures on hazy exoplanets.

Another analysis extends that argument by outlining specific spectral combinations that would be especially hard to produce abiotically, even in exotic planetary environments. It emphasizes that robust biosignature claims will likely rest on multiple lines of evidence, including atmospheric composition, surface temperature, and stellar context, rather than a single “smoking gun” molecule. I find that perspective compelling, and it is echoed in broader discussions of how JWST alien biosignatures might be identified without over-interpreting ambiguous data.

Designing observing strategies for life-friendly atmospheres

Turning those theoretical biosignature frameworks into practical observing programs requires careful choices about which planets to prioritize and how to allocate Webb’s limited time. Researchers are increasingly focusing on temperate, Earth-sized or slightly larger planets around small, cool stars, where the transit signal is relatively strong and orbital periods are short enough to stack multiple observations. A detailed roadmap for this strategy, including how to balance the need for signal-to-noise with the desire to sample a diverse set of targets, is laid out in an analysis of how Webb could find signs of alien life in exoplanet atmospheres.

In my view, the key insight is that no single planet will settle the life question; instead, Webb will build a statistical picture of how often potentially habitable atmospheres occur and how varied they are. That means accepting that some targets will yield ambiguous or featureless spectra, especially if clouds or hazes are thick, while others may offer clearer windows into their chemistry. Over time, those results will inform the design of future missions that can directly image Earth-like planets and probe their atmospheres with even greater precision.

Public fascination and the culture around Webb’s discoveries

Webb’s exoplanet breakthroughs are not unfolding in a vacuum; they are being watched, debated, and celebrated by a global audience that follows each new spectrum almost in real time. Public talks and explainers, including widely viewed presentations such as a JWST exoplanet discussion that walks through early atmospheric results, have helped translate technical plots into narratives about alien weather and potential habitability. I see that communication as essential, because it shapes how taxpayers, students, and policymakers understand what is at stake in funding future observatories.

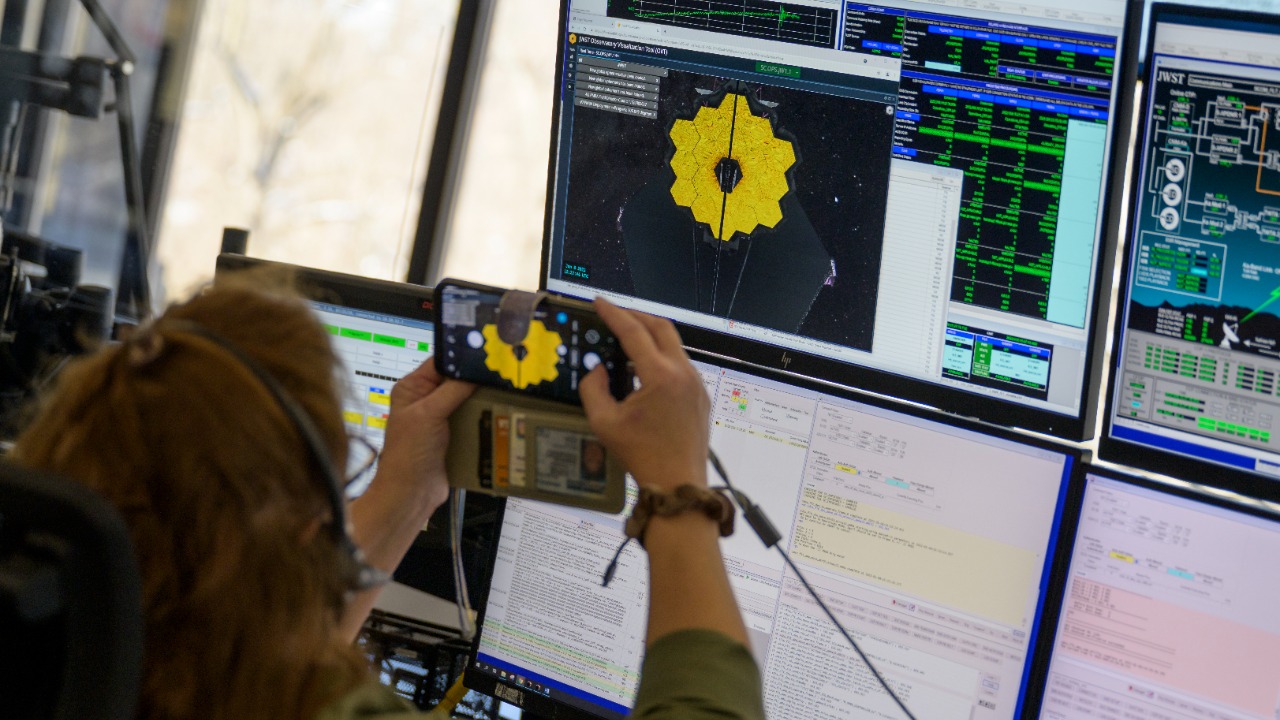

At the same time, informal communities have become hubs for sharing images, preprints, and spirited interpretations of Webb data, from cautious analyses to more speculative takes on what certain features might mean. One example is a dedicated James Webb Space Telescope group where enthusiasts dissect each new release and often surface questions that echo those being asked inside research teams. That feedback loop between professional science and public curiosity is part of what makes Webb’s exoplanet work feel like a shared exploration, even as the underlying measurements demand patience and restraint.

What the early results really tell us about life beyond Earth

With every new atmospheric spectrum, it becomes clearer that Webb is not a magic life detector but a powerful context machine, revealing how diverse planetary environments can be. The telescope is already showing that some close-in rocky worlds can retain unexpected atmospheres, that others around cool stars may be stripped or compact, and that giant planets host chemistry and clouds that defy simple classification. Those patterns are the groundwork for any future claim about habitability, because they tell us which combinations of star, planet, and orbit are most likely to support stable, temperate skies.

For now, the most responsible stance is to treat Webb’s exoplanet results as a map of possibilities rather than a catalog of inhabited worlds. I expect that the most profound impact will come not from a single dramatic announcement but from the cumulative weight of dozens of carefully vetted spectra, each one sharpening our sense of how rare or common life-friendly atmospheres might be. In that sense, the telescope is already delivering on its promise: it is turning the question “Are we alone?” into a set of testable hypotheses written in the light of alien skies.

More from MorningOverview