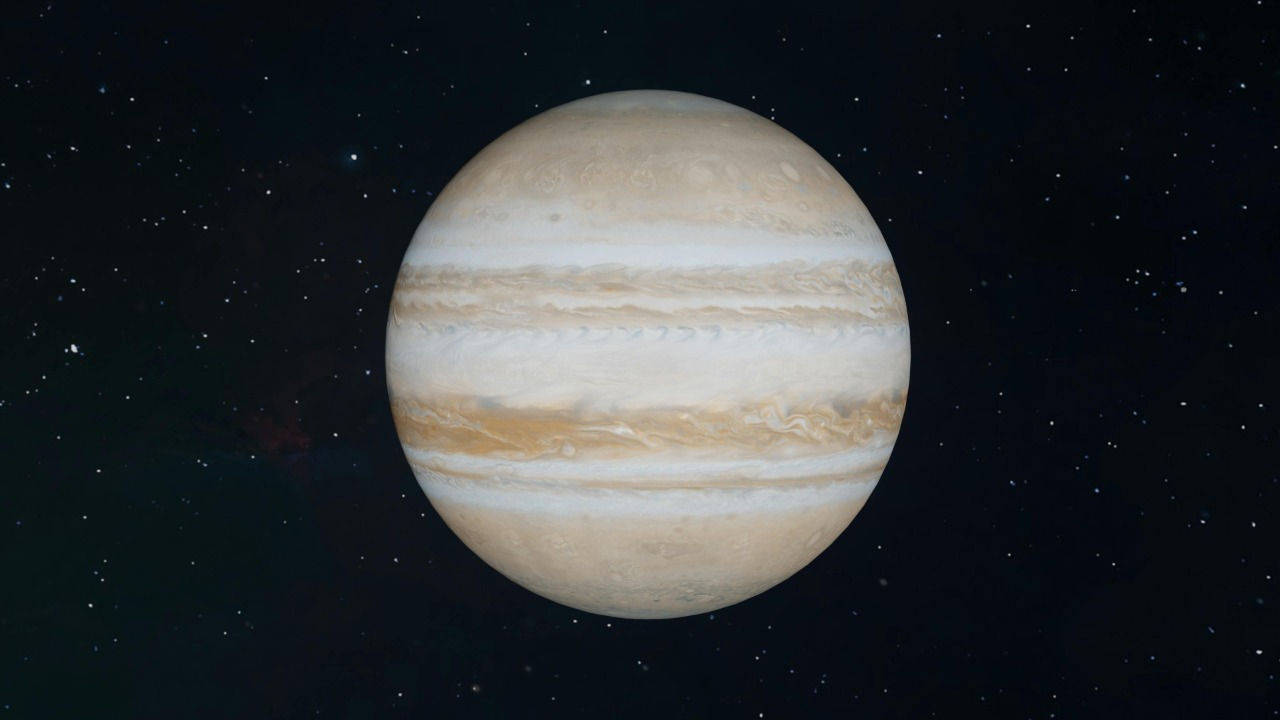

Jupiter has just been put on a cosmic diet. New measurements led by an Israeli team show that the giant planet’s diameter is about 8 kilometers smaller than long‑standing estimates and that its poles are more flattened than scientists realized. The result forces a subtle but important rethink of how I, and many planetary scientists, picture the structure and dynamics of the solar system’s heavyweight world.

Instead of a neat, almost spherical ball of gas, Jupiter now looks more like a rapidly spinning, squashed globe whose exact size depends on how precisely we define its “surface.” By tightening that definition and using sharper data than were available in the past, the researchers have trimmed Jupiter’s dimensions and opened a fresh window on the physics playing out deep inside its atmosphere.

How an Israeli-led team shrank the solar system’s giant

The new result comes from work led by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of, who set out to refine Jupiter’s basic dimensions rather than hunt for a dramatic new phenomenon. By combining spacecraft data with a stricter definition of the planet’s reference pressure level, they concluded that Jupiter, while still the largest planet in the solar system, is slightly smaller and more compressed at the poles than standard textbooks have long claimed. I see this as a classic example of precision science: the numbers shift only by a few kilometers, but the implications ripple through models of the planet’s interior and atmosphere.

Earlier estimates of Jupiter’s size relied heavily on radio measurements from NASA missions that flew past the planet decades ago. Those flybys were pathbreaking, but they left room for uncertainty in exactly where to draw the line that counts as Jupiter’s “surface,” especially in a world made almost entirely of gas. The Israeli-led team tightened that definition and folded in more recent data, which allowed them to argue that Jupiter is not only a bit smaller than we thought but also more distinctly oblate, with a noticeable difference between its equatorial and polar diameters.

Juno’s radio trick: taking Jupiter’s measure without a surface

Getting a precise size for a gas giant is not as simple as pointing a camera and measuring pixels. Instead, scientists define Jupiter’s effective surface at a standard pressure of 1 bar, the same pressure as Earth’s sea level, then work out where that level sits inside the swirling atmosphere. To do that, they use a technique called radio occultation, in which a spacecraft sends radio signals through the planet’s atmosphere to Earth and researchers track how those signals bend and slow as they pass through different layers. The latest work builds on this approach, using it to pin down the altitude of the 1‑bar level with unprecedented accuracy.

The most recent and precise occultation data come from The Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016 and has carried out 13 separate radio occultation experiments. Each experiment sends a radio beam skimming through the atmosphere, then analysts reconstruct the density and temperature profile from the way the signal is distorted. Earlier missions, including Voyager and Pioneer, managed only a combined total of 6 such measurements over roughly 40 years, which left larger error bars on Jupiter’s dimensions. With Juno’s richer dataset, the Israeli team could refine the planet’s shape with far greater confidence.

A planet more squashed than the textbooks say

What emerges from the new analysis is a Jupiter that is not just marginally smaller, but also more clearly flattened at the poles than earlier models suggested. The team finds an equatorial diameter of 142,976 kilometers and a polar diameter of 133,684 kilometers, a difference that highlights how strongly the planet’s rapid rotation stretches it outward around the middle. In practical terms, Jupiter is less like a perfect sphere and more like a spinning water balloon, with its equator bulging and its poles pressed inward.

That extra flattening, sometimes called oblateness, matters because it encodes information about how mass is distributed inside the planet. A more squashed shape implies that Jupiter’s outer layers respond in a particular way to rotation and gravity, which in turn constrains how dense its deeper interior can be. The new measurements, which show a greater degree of oblateness than previously recorded, will feed directly into models that try to infer whether Jupiter has a compact core, a diffuse one, or something in between. For planetary scientists, that is not a cosmetic detail, it is a clue to how the planet formed and evolved.

Why a few kilometers matter for planetary science

At first glance, trimming about 8 kilometers off a world that spans more than 140,000 kilometers across the equator might sound trivial, like sanding a fraction of a millimeter off a basketball. Yet in precision astronomy, those small differences can have outsized consequences. Gravity fields, atmospheric circulation patterns, and even the orbits of nearby moons all depend subtly on the exact size and shape of the planet they encircle. When I look at the new Jupiter numbers, I see a quiet but important tightening of the screws on many of the models that underpin our understanding of the Jovian system.

The updated dimensions also help reconcile spacecraft data with ground‑based observations that have hinted at complex dynamics in Jupiter’s deep atmosphere. By anchoring the 1‑bar level more firmly, the Israeli team gives theorists a sharper reference point for comparing cloud‑top winds, thermal emission, and gravity measurements. The refined shape, supported by the radio occultation data, effectively locks down the outer boundary condition for simulations of Jupiter’s interior. That, in turn, can influence estimates of how heat flows from the core to space and how the planet’s powerful magnetic field is generated.

From Jupiter to exoplanets: a new benchmark for gas giants

There is also a wider payoff to getting Jupiter’s size and shape right. Astronomers routinely use our own gas giants as benchmarks when they interpret data from exoplanets that transit distant stars. If Jupiter’s radius or oblateness is off, even by a little, that error can propagate into the way we calibrate models of alien worlds that are “Jupiter‑like” in mass or composition. The new measurements, which show Jupiter to be slightly smaller and more compressed at the poles, sharpen that benchmark and give exoplanet researchers a more reliable template for what a mature gas giant should look like.

For the Israeli team at the Weizmann Institute of, the work underscores how much information still hides in data from missions that are already in flight. By revisiting Juno’s occultation experiments with fresh questions and more sophisticated analysis, they have managed to “deflate” Jupiter slightly and reveal a more nuanced picture of its structure. For me, the lesson is clear: even in a solar system we have been studying for centuries, there is still room for surprises when we look with enough precision at the worlds we thought we knew best.

More from Morning Overview