The Strait of Hormuz is one of the most intensely monitored waterways on earth, yet beneath its shallow, noisy surface Iran has built a submarine threat that is deliberately hard to hear and even harder to track. By pairing heavy “black hole” diesel boats with swarms of tiny coastal subs, Tehran is trying to turn this chokepoint into a sonar nightmare for any carrier group that enters.

Instead of matching the United States ship for ship, Iran has invested in platforms that thrive in cluttered coastal waters and can disappear into the Gulf’s acoustic haze. Its Russian built Kilo class fleet, backed by midget Ghadir and newer Fateh designs, is optimized to exploit the geography and physics of the Strait, forcing U.S. and allied navies to fight in an environment where their technological edge is sharply blunted.

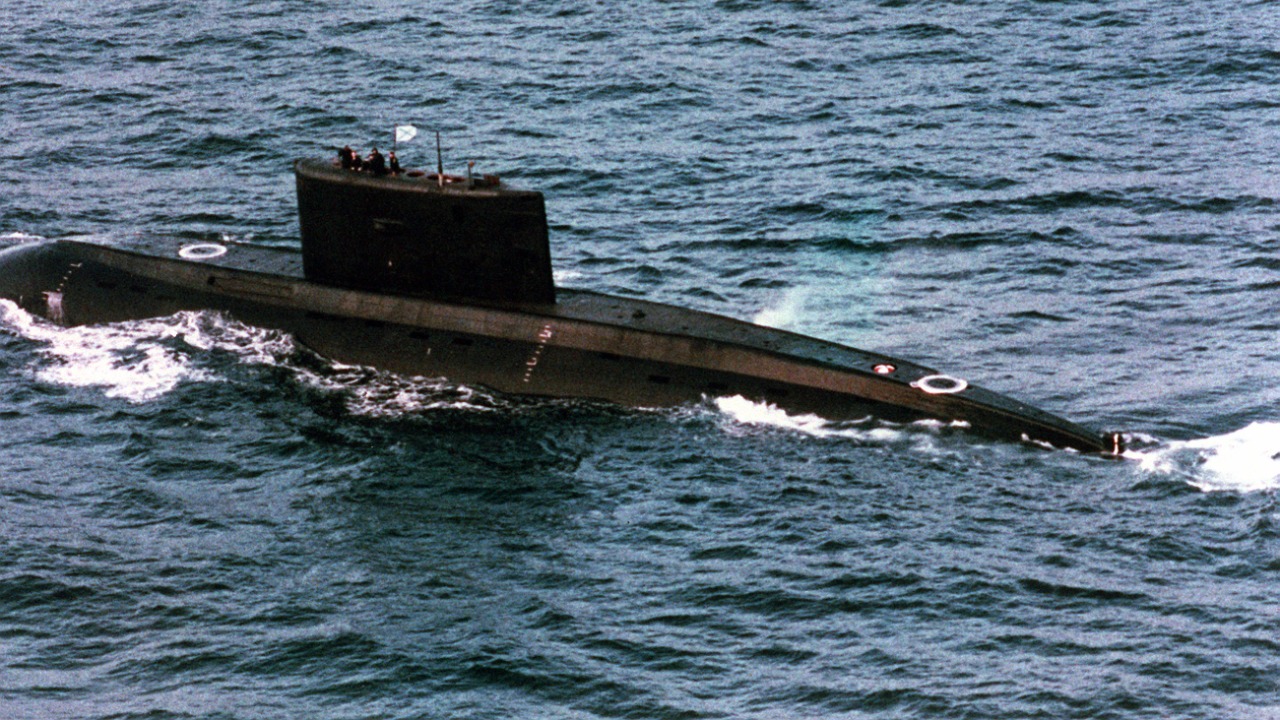

How Russia’s “black hole” boats ended up in Iranian hands

Iran’s undersea strategy starts with three heavy diesel electric submarines acquired from Russia in the 1990s, part of the export line of the Project 877 family that NATO labels the Kilo class. These boats, known in the Iranian navy as the Tareq class, were originally designed for the Russian Navy as coastal hunters that could lurk quietly near busy sea lanes for extended periods. Export variants of this Kilo class line were marketed specifically to states without nuclear submarines, and Both China and bought into the concept.

What makes these boats so feared is their acoustic profile. Western navies nicknamed them “black holes” because a well handled Kilo can be extremely hard to detect on sonar, especially when it is running slowly on batteries and coated in modern anechoic tiles. Later variants such as Project 636.3 added long range Kalibr cruise missiles, but even the older 877 series that Iran operates remains a serious threat in confined waters. Analysts describe the black hole label as more than a nickname, arguing that in the right conditions these subs can close to torpedo range before a surface commander realizes they are there.

A shallow chokepoint that punishes sonar

The Strait of Hormuz itself does much of the work for Iran. The narrow passage is deep enough for large tankers, but studies note that its typical depth of 82 to 131 feet is relatively shallow for submarines, forcing them to operate close to the surface where sound bounces unpredictably between the seabed and the air water boundary. High salinity and complex currents in the Gulf further distort acoustic propagation, creating layers and eddies that can scatter or trap sonar energy.

Those same environmental quirks limit Iran’s own heavy boats. Analysts point out that The Kilos require a depth of at least 164 feet to sail safely, which makes nearly two thirds of the Gulf effectively off limits to them. Yet that same constraint channels traffic into predictable deep water corridors, and within those lanes the combination of shallow depth, salinity and background shipping noise can make anti submarine warfare a frustrating exercise. Research on acoustic conditions in the region underscores how cluttered the sonar picture becomes, especially for towed arrays trying to distinguish a slow diesel boat from merchant traffic.

From Tareq to Ghadir and Fateh: a layered undersea force

Because the big Kilos cannot roam freely across the shallows, Iran has filled the gaps with a growing fleet of small submarines designed specifically for coastal ambush. Open source assessments describe at least a dozen Ghadir class midget boats, which are optimized for short range patrols, mine laying and torpedo attacks in the narrowest parts of the Strait. Analysts warn that Ghadir hulls are hard to detect and can lie in wait along shipping routes, complementing the presence of the larger Introducing the Kilo boats that signal a heavier Iranian presence in the critical waterway.

Tehran has also tried to bridge the gap between tiny midget subs and heavy Tareq hulls with an indigenous medium design. Reporting on Iran’s naval modernization notes that Iran has attempted to bridge its midget boats and heavy Kilos with the Fateh class, a diesel electric platform sized for the Gulf’s depth and tailored to operate in narrow spaces that favor ambush. According to detailed tallies of Iran’s three Tareq heavy submarines and their smaller cousins, this layered mix gives Tehran options ranging from covert minefields to torpedo salvos launched from multiple directions.

Turning a carrier transit into a “sonar horror zone”

For a U.S. carrier strike group entering the Strait of Hormuz, the result is an environment where threats can come from any depth and any direction, often masked by the very tankers the group is there to protect. Analysts argue that Iran’s three Kilo class Black Hole Submarines are its most capable undersea assets, able to fire heavyweight torpedoes and potentially anti ship missiles at high value targets. At the same time, the Some reports that Iran has experimented with weapons like a reverse engineered Russian Shkval style supercavitating torpedo only add to the uncertainty facing U.S. planners.

Iranian commanders have signaled their intent by publicizing deployments of submarines in and around the chokepoint, with regional reporting noting that Iran deploys submarines in the Strait of Hormuz as part of routine patrols and exercises. Strategic assessments of the Strait of Hormuz emphasize that even a small number of quiet boats, if positioned well, could threaten the world’s most important oil transit chokepoint and force the United States to commit disproportionate resources to anti submarine sweeps. In that sense, Iran does not need to guarantee a kill on a carrier to succeed; it only needs to make the undersea picture so uncertain that every transit feels like moving through a sonar horror zone.

Why the U.S. cannot ignore Iran’s undersea gamble

U.S. officials and analysts have sometimes dismissed Iran’s conventional navy as outdated, but the undersea piece of the puzzle is harder to wave away. Detailed assessments argue that Iran’s submarine threat deserves more attention precisely because it exploits American vulnerabilities in shallow, noisy littorals. Studies of Iran’s Russian built Kilo class boats stress that the Gulf’s high salt environment creates complex underwater currents that complicate acoustic detection, while the geography of the Strait of Hormuz limits maneuver room for large surface combatants.

At the same time, Iran is not relying on submarines alone. Reporting on its broader maritime posture notes that Tehran has boosted its fleet of mini submarines and fast missile craft, creating a combined arms threat in which small boats, shore based missiles and These submarines can exploit the region’s natural noise and clutter while drones engage targets from above. In that context, the Kilo class Stealth Submarines Were to Iran as prestige assets, but they now sit at the center of a wider strategy that aims to turn the Gulf into a place where even the most advanced navy must move slowly, listen carefully and accept that some threats will remain hidden.

More from Morning Overview