In the strange corner of modern physics where spacetime itself becomes the engine, the old rule that nothing can outrun light starts to look negotiable. Inside carefully engineered “bubbles” of distorted geometry, motion can appear to beat light without shattering Einstein’s speed limit, because it is space that moves, not the object inside. I want to unpack how this bubble world works, why it does not actually break relativity, and how a mix of theory and laboratory experiments is slowly turning a science‑fiction fantasy into a constrained but very real research program.

How relativity leaves a loophole for faster-than-light motion

The starting point is brutally simple: in Einstein’s special relativity, nothing with mass can locally move faster than light through space. That limit is baked into the structure of spacetime itself, not just into the performance of rockets or engines. Yet general relativity, which lets spacetime curve and stretch, quietly introduces a loophole. The speed limit applies to motion through spacetime, but not to the way spacetime can expand, contract, or ripple, which is why cosmologists are comfortable saying that very distant galaxies recede faster than light as the universe expands.

Warp concepts exploit exactly this distinction. Instead of pushing a ship to superluminal speed, they imagine sculpting a region of spacetime so that the distance between departure and destination shrinks in front of the craft and stretches behind it. In that picture, the vehicle never exceeds light speed relative to its immediate surroundings, but the bubble of distorted geometry can carry it effectively faster than light relative to faraway stars. That is the bizarre bubble where speeds can beat light without violating Einstein.

The Alcubierre idea and its exotic energy problem

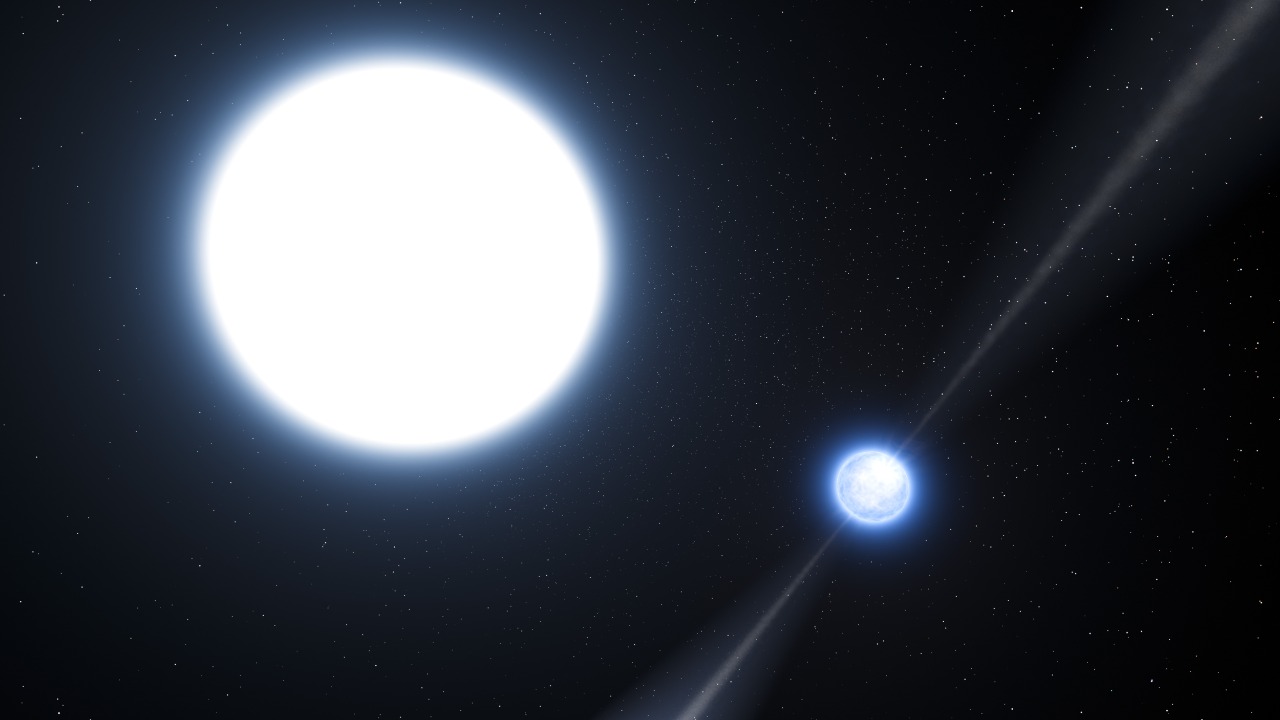

The most famous attempt to formalize this loophole is the metric proposed by Miguel Alcubierre, which describes a spacetime bubble that contracts space ahead of a ship and expands it behind. Mathematically, the construction is consistent with the Einstein field equations, so it sits inside accepted general relativity rather than outside it. In the Alcubierre picture, the craft rides in a central “flat” region where local physics looks normal, while the surrounding ring of warped geometry does the heavy lifting of apparent faster‑than‑light travel.

The catch is that the original Alcubierre solution demands negative energy densities, a kind of exotic matter that behaves the opposite way from ordinary mass. Analyses of the Alcubierre metric show that the required negative energy would be enormous, far beyond anything quantum effects like the Casimir vacuum can plausibly supply. Even simplified classroom treatments, such as the Alcubierre Warp Drive notes that describe a ring of negative energy around a ship, underline how far this is from engineering reality.

From science fiction to revised warp-drive models

Despite those obstacles, theorists have not abandoned the idea of bending spacetime as a propulsion trick. Over the past few years, several groups have tried to tame the energy requirements by tweaking the geometry of the bubble and the way it accelerates. A recent new warp‑drive model explicitly revises the Alcubierre idea to remove its biggest problem, the need for outright negative energy, while still allowing a bubble to move through space faster than light in principle. The mathematics is still idealized, but it shows that the original design was not the only way to imagine a warp bubble.

Other researchers have gone further and tried to connect these metrics to realistic propulsion concepts. A team of Researchers at UAH and the Applied Physics Lab, for example, argue that warp‑like motion is possible within known physics if spacetime distortion is treated as a propulsion concept rather than a magical shortcut. Their work sits alongside more popular explanations that describe how a warp drive would contract spacetime ahead of a spacecraft and expand it behind, creating a “warp bubble” that moves the craft without locally breaking the light barrier, as in one widely shared description of the concept.

Rochester’s microscopic bubbles where light seems to win the race

The most intriguing developments are not on paper but in the lab, where small experiments are starting to mimic the behavior of warp bubbles on microscopic scales. Physicists at the University of Rochester have been at the center of several such reports. In one widely discussed experiment, they created a real microscopic warp bubble that manipulated spacetime in a way that made light appear to travel faster than it normally would through the setup, even though no photon actually outran light in vacuum.

Accounts of this work describe a tiny region where advanced electromagnetic structures bend reality for passing light, a “tiny warp bubble” that makes signals arrive sooner than they would in an unmodified medium. One report on this tiny warp bubble emphasizes that the effect comes from manipulating spacetime using advanced electromagnetic structures, not from breaking relativity. Another summary of the same line of research notes that Physicists have created a microscopic spacetime bubble for faster information transfer, hinting at applications in quantum gravity tests and spacetime manipulation rather than starships.

Information transfer that outruns light without breaking it

Alongside the warp‑bubble experiments, the same Rochester community has reported clever ways to make information appear to beat light while still respecting relativity. In one groundbreaking experiment, physicists at the University of Rochester transmitted information in a way that seemed to cross the usual light‑speed barrier, yet the underlying signal structure kept causality intact. Another account of the same work describes how Physicists at the University of Rochester managed to make information appear to move faster than light by letting light effectively compete against itself.

These experiments rely on reshaping pulses, interference, and carefully engineered media so that the peak of a signal emerges earlier than a simple straight‑line path would allow. A separate discussion of how Physicists broke the speed of light barrier without breaking Einstein’s laws makes the same point: the trick is to manipulate the medium and the shape of the wave so that the information’s effective speed increases, while the fundamental light speed in vacuum remains untouched. In that sense, the Rochester work is less about cheating nature and more about learning how to choreograph light and spacetime so that our usual intuitions about speed no longer apply.

More from Morning Overview