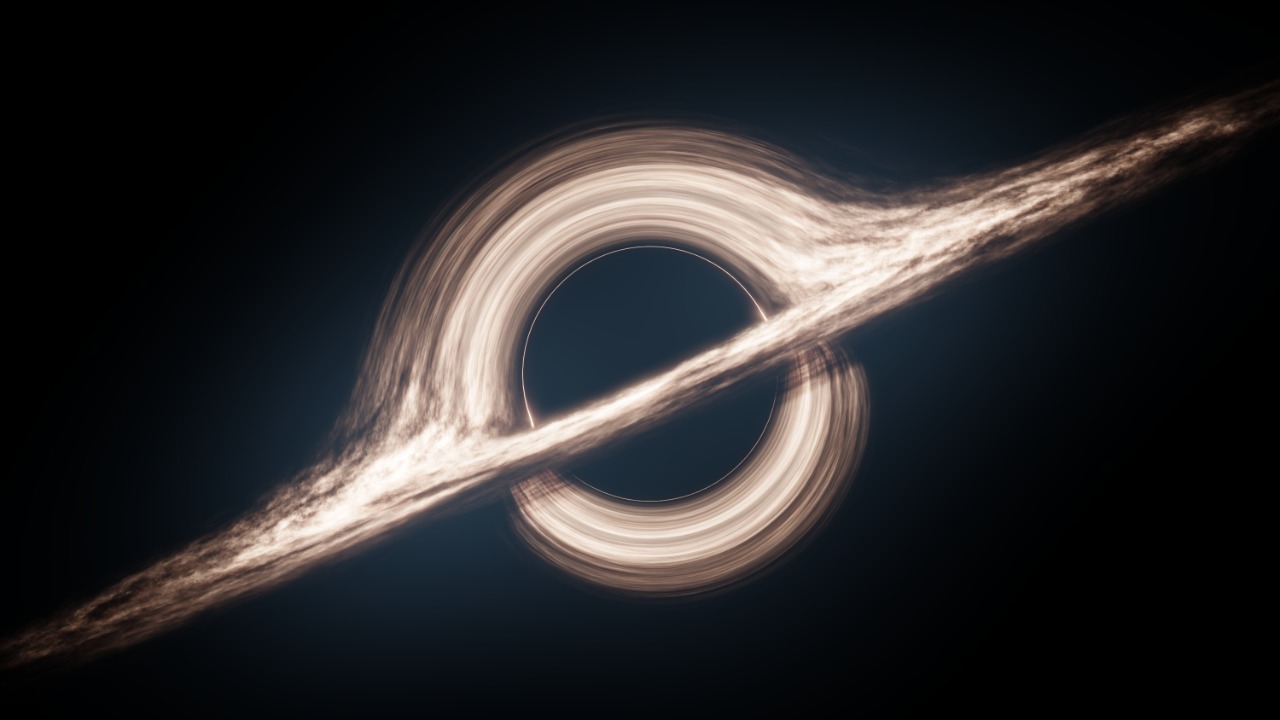

For decades, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way was an invisible monster, betrayed only by the way nearby stars whipped around an unseen mass. When astronomers finally unveiled its portrait, the blurry orange ring was more than a pretty picture, it was proof that humanity could turn an entire planet into a single, exquisitely tuned instrument. I see that image of Sagittarius A* as the culmination of a global bet that Einstein’s equations, radio engineering, and patient data wrangling could tame one of the universe’s most secretive objects.

The hidden giant at the heart of the Milky Way

Long before anyone tried to photograph it, astronomers knew there was something extraordinary lurking in the constellation Sagittarius. Precise measurements of stellar orbits pointed to a compact object with millions of times the Sun’s mass packed into a region smaller than our solar system, a textbook signature of a supermassive black hole. That object is now widely known as Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A*, and the observed radio and infrared energy around it comes from gas and dust heated to millions of degrees as it spirals inward toward the central black hole.

Scientists suspected that almost all galaxies host similar behemoths, but the one in our own backyard was a particularly tantalizing target. It sits roughly 26,000 light-years away, close enough that its event horizon appears on the sky about as large as a donut on the Moon would look from Earth. At the same time, it is relatively quiet, which makes it much fainter than some active galactic nuclei and therefore harder to see against the surrounding glow. Observatories studying the galactic center, including facilities coordinated through the MIT Haystack Observatory, helped pin down its behavior and location so that imagers would know exactly where to point.

From theory to target: why Sagittarius A* mattered

For much of the twentieth century, black holes lived mostly in equations and thought experiments. General relativity predicted that a sufficiently dense mass would curve spacetime so strongly that not even light could escape, but no one expected to see the edge of that region directly. As radio astronomy matured, however, the compact source at the Milky Way’s center emerged as a natural laboratory to test Einstein’s theory in the strongest gravitational fields accessible, turning Sagittarius A* into a prime target for a.

When the first direct image of a black hole’s shadow came, it was not from our galaxy but from a much larger object in the galaxy M87. That earlier success proved that the same approach could work closer to home, even though Sagittarius A* is smaller and its hot gas flickers more rapidly. Analyses of the Milky Way’s core showed that the physics of light bending and accretion should still produce a ring-like silhouette, just as predicted by general relativity. Researchers who later unveiled the Milky Way image emphasized that years of analysis were needed to tease that pattern out of the noisy, rapidly changing data.

Building a telescope the size of Earth

The core challenge in imaging any black hole is resolution. To see something as small on the sky as Sagittarius A*’s shadow, astronomers effectively needed a telescope as large as the planet. Instead of constructing a single impossible dish, they used a technique called very long baseline interferometry, linking radio observatories around the globe so they could act as one. The resulting Event Horizon Telescope network was designed specifically to capture the silhouette of supermassive black holes.

In place of that logistical impossibility of a literal Earth-sized mirror, the collaboration synchronized eight radio observatories in locations including Greenland, Chile, and the South Pole to watch their target from multiple angles. Earlier campaigns that focused on the black hole in M87 had already demonstrated that this global array could deliver the necessary sharpness. The telescopes they used stretched from Hawaii and Arizona to Mexico, Spain, Chile, and the South Pole, with data ultimately shipped to processing centers linked to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston.

Turning a planet’s worth of data into a single image

Capturing the raw signals was only the beginning. Each observatory recorded torrents of radio data on hard drives, all time-stamped with atomic clocks so they could later be combined. The volume of information collected was so enormous that, as EHT data scientist Lindy Blackburn noted, it was literally too large to send over the internet and had to be physically transported to central correlators. There, specialized algorithms stitched together the signals from each pair of telescopes, reconstructing how the black hole’s surroundings must have looked.

Because Sagittarius A* is smaller than the M87 black hole, the hot gas around it orbits in minutes instead of days, which meant the target changed while the array was observing. That variability blurred the picture and forced researchers to develop new imaging strategies that could average over many possible snapshots while still preserving the underlying ring. Teams tested independent pipelines, compared results, and only converged on a final image after they were confident that the bright ring and central shadow were robust features. The collaboration’s own EHT updates have described how years of method development and cross checks were essential to turn noisy radio traces into a scientifically trustworthy portrait.

From M87 to our “monster” black hole

The road to the Milky Way image ran through another galaxy. Earlier work had already shown that a decades-old interferometry technique, combined with a remarkable global collaboration, could reveal the shadow of the much larger black hole in M87. That first success confirmed that the Event Horizon Telescope, often shortened to EHT, could deliver on its promise. In a historic breakthrough, an international team of scientists announced that they had captured the first-ever image of a black hole and pointed interested readers to the Event Horizon Telescope for more technical details.

When the focus shifted to our own galaxy, the stakes felt different. The Milky Way’s central black hole is much closer but also much dimmer, meaning it is harder to distinguish from the surrounding clutter of stars and gas. Reports on the Milky Way’s monster emphasized that the object is far less luminous than some active galactic nuclei, which made the imaging challenge more subtle. Yet the same ring-like shape emerged, matching what general relativity predicts for light skimming the edge of a spinning black hole’s event horizon.

More from Morning Overview