Life on Earth may have started with a molecule that still runs our cells today. As researchers probe ribonucleic acid in the lab and in ancient rocks and space dust, RNA is yielding clues that are far stranger and more specific than the old textbook sketches of a “primordial soup.” Together, these findings are turning a once-speculative “RNA world” into a testable story about how chemistry became biology.

In that story, RNA is not just a passive messenger between DNA and proteins but a shape-shifting catalyst, a genetic archive, and a bridge between lifeless minerals and the first cells. I see a pattern emerging from new experiments, asteroid samples, and computer models: RNA keeps showing up at the scene of life’s origin, and each new result tightens the case that it was the first great organizer of living matter.

From bold idea to working model of an RNA world

The modern case for an RNA-centered origin began with The RNA World Hypothesis, which argued that before DNA and proteins, there was a period when RNA alone stored information and catalyzed reactions. Visionaries such as Salk Fellow Leslie Orgel helped frame that idea in the 1960s, and it has since evolved from a thought experiment into a framework that can be probed in the lab. The concept is simple but radical: a single type of molecule could have handled both genetic coding and basic metabolism in an early World.

Recent work has sharpened that picture. Because it is a simpler molecule than DNA, RNA is thought to have formed first, and thanks to its ability to carry genetic information and catalyze reactions, it could plausibly have copied itself before proteins existed. That dual role is now being explored in controlled experiments that test how RNA behaves under early Earth conditions, and in theoretical work that asks how such a molecule might have emerged from a chaotic mix of simpler chemicals described in a classic chapter on the RNA world.

Simulating a planet that could build RNA

To move beyond broad theory, scientists have started to reconstruct the physical settings that could have nurtured RNA. One influential line of work imagines a violent early Earth struck by a 500-kilometer-wide (310 miles) protoplanet, similar in size to the asteroid Vesta, which would have melted crustal rock and created long-lived pools of magma and water. Hirakawa and colleagues argue that such an impact could have concentrated the right elements and left behind mineral deposits, including zircon, that preserve a record of those extreme conditions on Hirakawa.

In parallel, other teams are asking whether the building blocks of RNA might have arrived from space. Samples returned from the asteroid Bennu to Earth contain organic molecules that match some of the ingredients needed for nucleic acids, bolstering the idea that impacts could have delivered key precursors. These findings have also been bolstered by new discoveries about the sample of material brought to Earth from the asteroid Bennu, which now sit alongside impact models to suggest that planetary collisions and meteorites may have worked together to seed the young planet with the raw material for RNA.

RNA that copies itself and starts to work

For the RNA world idea to hold, RNA must be able to replicate without the help of modern enzymes. Chemists at University College London have demonstrated how RNA might have reproduced for the first time, showing that strands can grow and copy information when supplied with activated building blocks and the right temperature cycles. In that work, Chemists showed that short templates could guide the assembly of complementary strands, hinting at a path from random polymers to a primitive genetic system, as described in a study from University College London.

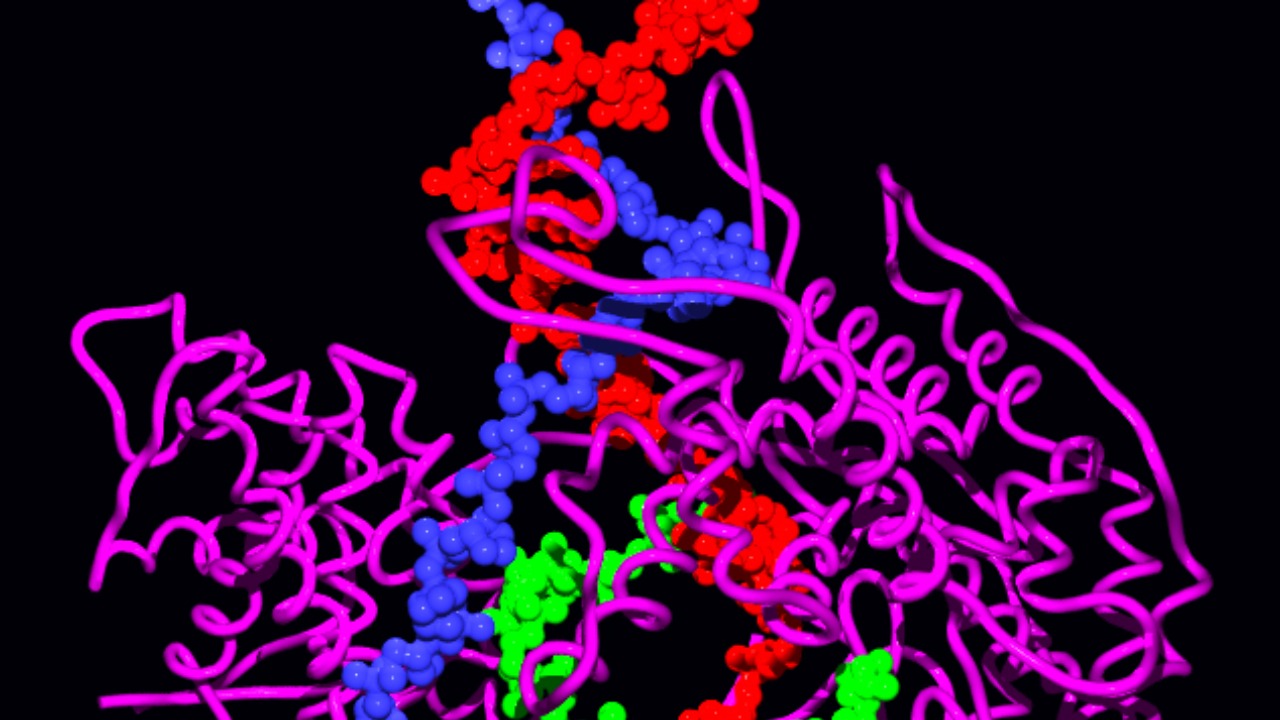

Other experiments have focused on how RNA could have taken on catalytic roles before proteins. The large and ever-increasing repertoire of RNA enzymatic function provides a priori support for the idea of RNA-based protein-less life, as cataloged in a detailed synthesis of RNA chemistry. In that view, ribozymes, RNA molecules that fold into active shapes, could have stitched together nucleotides, managed energy-rich bonds, and even helped assemble the first peptides long before modern enzymes evolved.

Linking RNA to the first proteins

One of the most striking advances has been the recreation of a plausible first step toward protein synthesis. Researchers have shown that amino acids can spontaneously attach to RNA under early Earth-like conditions using thioesters, producing short chains that resemble primitive peptides. In those experiments, Researchers demonstrated how amino acids could spontaneously attach to RNA, suggesting a route by which the earliest peptides may have formed on a young Earth.

That chemistry dovetails with a broader effort to understand how RNA might have started to make proteins on early Earth. An Origin Of Life Breakthrough project titled How RNA Might Have Started To Make Proteins On Early Earth has been described in a Press Release and follow up reporting By Keith Cowing, highlighting how specific RNA sequences can bind amino acids and promote bond formation. The same Origin Of Life Breakthrough, framed within Astrobiology and the Origin and Evolution of Life, has been used to argue that such RNA based systems could have been the missing link between a pure RNA world and the modern translation machinery, as detailed in work from Origin Of Life.

Recreating an RNA world in the lab

Beyond individual reactions, scientists are now trying to assemble whole networks of RNA-based processes that resemble a primitive cell. At the Salk Institute, New research has modeled how RNA strands could have formed, folded, and interacted in a dynamic environment, providing fresh insights on the origins of life and presenting compelling evidence supporting an RNA World hypothesis. In that work, Scientists used computer simulations and wet-lab experiments to show how simple RNA systems could evolve toward more complex, information-rich states, as described in a detailed report on Scientists.

Other teams have taken a more direct approach, trying to recreate the first thing that ever lived on Earth in miniature. In one widely discussed effort, Scientists have moved closer to recreating such an entity in the lab, using lab-created chemicals and controlled environments to coax RNA and related molecules into self-organizing structures. That work, covered by WKRC on a Sat morning segment, underscores how far experimentalists have come from abstract theory toward tangible protocells that blur the line between chemistry and life on Scientists.

More from Morning Overview