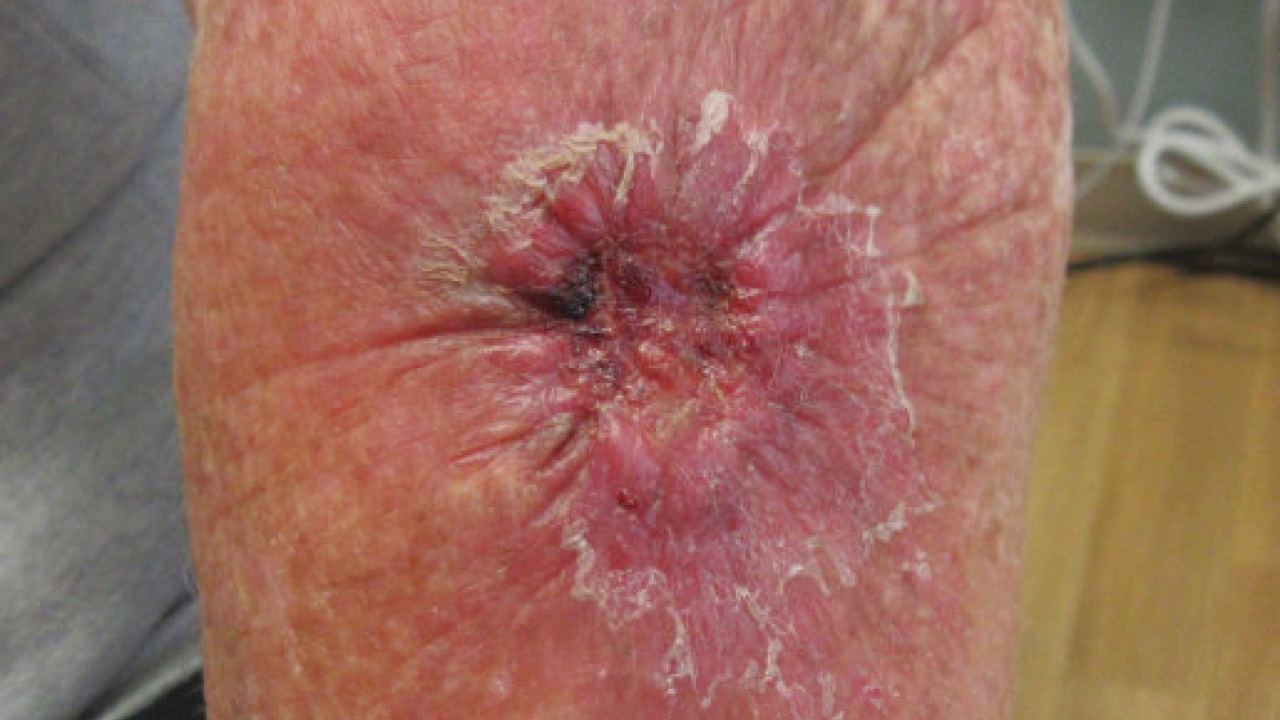

Melanoma has long been defined by rogue pigment cells and sun damage, but a new line of research points to a surprising accomplice hiding in plain sight on human skin. A common body fungus, usually dismissed as a harmless passenger, appears capable of rewiring melanoma cells into a more invasive, treatment‑resistant form. The finding suggests that the deadliest skin cancer may, in part, be turbocharged by microbes we carry every day.

Instead of acting alone, melanoma cells seem to sit inside a complex ecosystem of bacteria and fungi that can either restrain or accelerate disease. Early data now indicate that one fungal resident, Candida albicans, can push tumors toward a more aggressive, metastatic behavior, raising urgent questions about how dermatology, oncology and infectious disease medicine should intersect in the clinic.

The everyday fungus with a dark side

For most people, Candida albicans is an unremarkable part of daily life, quietly occupying the mouth, gut, skin and genital tract without causing symptoms. In healthy individuals it typically behaves as a commensal organism, living on the skin and mucosa while the immune system and other microbes keep it in check, as detailed in work on the human fungal pathogen Candida. Problems arise when that balance breaks, for example in people receiving chemotherapy or broad‑spectrum antibiotics, where the fungus can overgrow and invade tissue.

Once it escapes its usual niches, Candida albicans can cause systemic candidiasis, a life‑threatening infection that often originates in the gastrointestinal tract. The evidence is described as overwhelming that C. albicans in the gastrointestinal tract is a major source of bloodstream infection, with the organism able to translocate through the intestinal barrier into circulation, according to analyses of systemic candidiasis. That capacity to shift from benign colonizer to invasive pathogen is central to why oncologists are now paying closer attention to the fungus in the context of cancer.

How Candida albicans supercharges melanoma cells

In new experimental work, researchers exposed melanoma cells to Candida albicans and watched the cancer adopt a more dangerous profile. The fungus appeared to enhance melanoma aggressiveness through signaling pathways that included p38‑MAPK and HIF‑1α, molecular switches linked to stress responses and low‑oxygen survival, according to a detailed study of melanoma aggressiveness. When those pathways were activated, melanoma cells showed traits associated with invasion, survival under stress and potential resistance to therapy.

Laboratory models suggested that direct interaction between tumor cells and the fungus was enough to shift the cancer toward a more metastatic phenotype. In an overview of the work shared on social media, the team reported that Candida albicans exposure drove melanoma toward a more aggressive phenotype and higher metastatic potential, a summary that aligns with the mechanistic data on higher metastatic potential. Taken together, the findings suggest that a fungus long viewed as a background player can directly tune the behavior of malignant cells.

From skin microbiome to full‑blown cancer ecosystem

The idea that microbes influence melanoma is not entirely new, but the focus has largely been on bacteria rather than fungi. There is growing recognition that the skin microbiome, which includes bacteria, viruses and fungi, is closely linked to melanoma onset, progression and responses to immunotherapy, according to a broad review of the skin microbiome. There is particular interest in how local microbes shape immune surveillance in the skin, which is critical for catching and destroying early malignant cells.

Within that ecosystem, Candida albicans stands out because it can colonize the skin as well as cause systemic infections. Therefore, given that C. albicans can occupy the same cutaneous environment as melanoma cells, it has the potential to interact directly with tumors and the surrounding immune cells, a possibility highlighted in mechanistic work on C. albicans. I see this as a shift from thinking about melanoma as a purely genetic disease to viewing it as a product of constant crosstalk between tumor cells, immune defenses and resident microbes.

Fungi as co‑conspirators in cancer development

The melanoma findings fit into a broader pattern in which fungi appear to act as co‑conspirators in several cancers. Reviews of fungal infections in carcinogenesis describe how species such as Candida albicans and Blastomyces spp. are implicated in cancer initiation and progression, with ample evidence that C. albicans is able to initiate and develop cancerous events more efficiently than other species of Candida, as summarized in work on fungal carcinogenesis. Among these fungi, the capacity of C. albicans to adhere to tissue, form biofilms and secrete damaging enzymes appears to give it particular leverage over host cells.

Mechanistically, fungi can promote cancer through several routes. Detailed analyses describe at least four processes: induction of inflammatory pathways that support proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis, molecular mimicry that interferes with cell signaling, direct production of carcinogenic metabolites and a Th17‑skewed immune response that antagonizes IL‑12 and interferon, as outlined in a comprehensive review of fungal mechanisms. I read the melanoma data as another example of this pattern, with Candida albicans using its inflammatory and signaling toolkit to tilt the tumor microenvironment in its favor.

What this means for screening, treatment and everyday care

If a common fungus can accelerate melanoma, the implications for screening and treatment are significant. One immediate question is whether dermatologists should pay closer attention to fungal colonization on or around suspicious pigmented lesions, particularly in patients who are immunosuppressed or receiving targeted therapies. The majority of opportunistic oral mucosal fungal infections are already known to be due to Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus species, according to a review of opportunistic infections, which suggests that similar overgrowth on the skin could be clinically relevant in high‑risk patients.

At the same time, any move toward antifungal strategies in melanoma will need to be grounded in a nuanced understanding of the skin microbiome. There is growing interest in how manipulating local microbes might improve responses to immunotherapy and bacteriotherapy, as highlighted in work on microbiome‑linked treatment responses. I expect future trials to test whether carefully targeted antifungal approaches, perhaps combined with immune‑modulating therapies, can blunt the pro‑tumor influence of Candida albicans without destabilizing the broader microbial community that helps protect the skin.

More from Morning Overview