General Motors has spent years pitching plug-in hybrids as a practical bridge between gasoline and fully electric cars, but the company’s own chief executive is now acknowledging a problem that cuts to the heart of that strategy. When drivers do not actually plug these vehicles in, the promised climate benefits evaporate and the emissions picture starts to look uncomfortably close to a conventional car. For buyers who chose a plug-in to shrink their carbon footprint, the latest data is a jarring reminder that technology alone cannot deliver cleaner transport if human behavior does not cooperate.

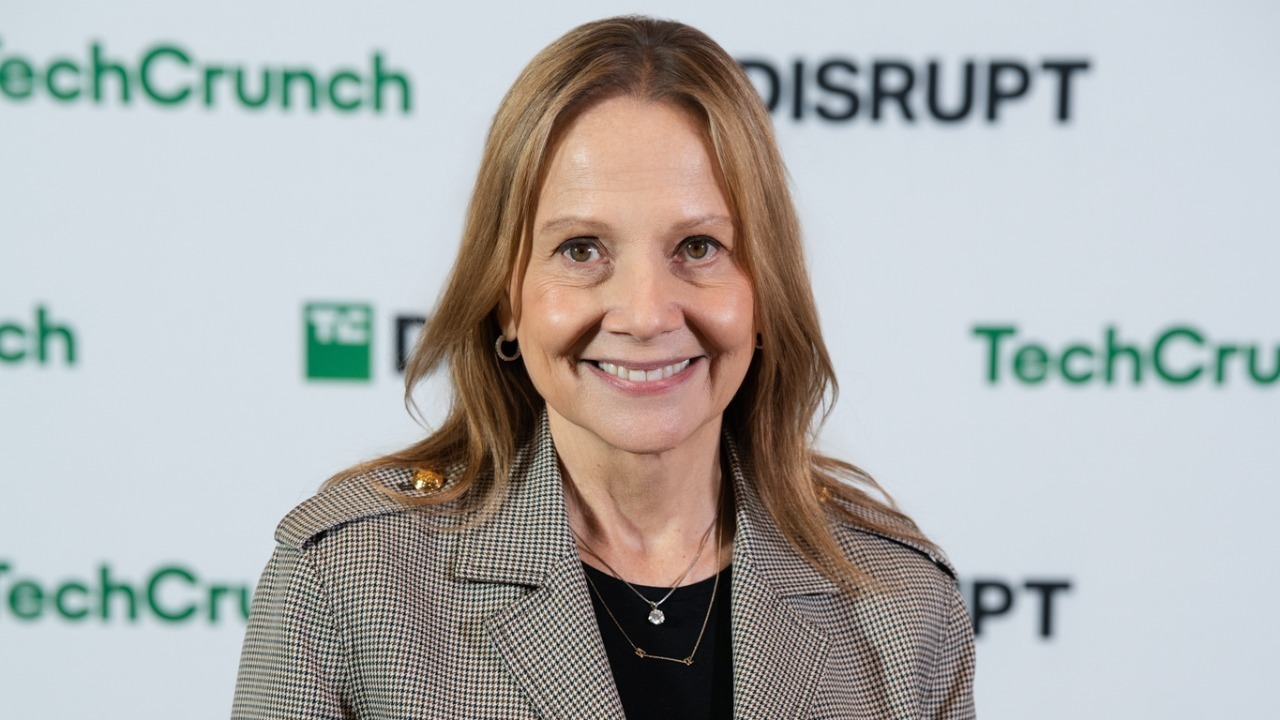

Mary Barra’s blunt assessment of how customers are using these cars has collided with new emissions research that tracks what happens when plug-in hybrids are treated like ordinary gas vehicles. The result is a rare moment of candor from a major automaker about the limits of a product it still sells, and a warning to regulators who have been counting plug-in hybrids as a low-risk way to hit climate targets. I see it as a turning point that forces a more honest conversation about how these vehicles are designed, marketed, and measured.

The “fatal flaw” Mary Barra just put on the record

At the center of the controversy is a simple admission from GM’s chief executive officer, Mary Barra, that many owners of plug-in hybrids are not actually charging them. In public remarks that have rippled across the industry, the CEO acknowledged that people are buying these vehicles for their flexibility but then skipping the one behavior that makes them cleaner, which is plugging them in regularly. When a plug-in hybrid is driven mostly on its gasoline engine, the electric hardware becomes extra weight and cost rather than a meaningful emissions solution.

That is the “fatal flaw” Mary Barra has now attached to plug-in hybrids, a phrase that captures how a technology designed to cut fuel use can backfire when real-world habits diverge from lab assumptions. The company’s own internal analysis, reflected in outside reporting on emissions data, shows that when drivers fail to charge, tailpipe pollution climbs far above the optimistic figures printed on window stickers. In other words, the hardware works, but the system fails because it depends on a daily routine that many owners are not willing or able to maintain.

Emissions data that shocks drivers who thought they were “green”

The numbers behind Barra’s warning are particularly sobering for drivers who chose a plug-in hybrid believing it would dramatically cut their climate impact. Laboratory tests assume a high share of electric driving, yet usage studies are finding that a large portion of miles in these vehicles are still powered by gasoline. When the battery is rarely charged, the car’s real-world fuel consumption can approach that of a standard internal combustion model, even though the official rating suggests something much cleaner.

Reporting on the “Mary Barra Admits” and “Fatal Flaw” narrative has highlighted how this gap between test cycles and daily use is not a marginal issue but a structural one for plug-in hybrids. The same sources that describe the “Plug” and “In Hybrids” problem also point to how the “Emissions Data Proves It” by documenting higher-than-expected fuel burn in mixed driving. For people interested in efficient cars, the revelation that their plug-in may be emitting far more than they assumed is not just a technical footnote, it is a direct challenge to the green identity that often accompanies these purchases, as detailed in the analysis of people interested in efficient cars.

Behavior, not batteries, is defeating plug-in hybrids

What Barra is really surfacing is a human-factors problem that engineers alone cannot solve. Plug-in hybrids were designed around the idea that owners would treat them like smartphones, topping up the battery at home or work so that most daily trips could be electric. Instead, many drivers are treating them like traditional cars with a bonus feature, relying on the gas tank and ignoring the charge port except on road trips or special occasions. That mismatch between design intent and user behavior is where the climate math breaks down.

Earlier this year, GM’s CEO Mary Barra put it bluntly by saying that people are not plugging in their plug-in hybrids and that this defeats their whole purpose. Her comments, captured in coverage that also references the figure “202” in the context of the broader plug-in debate, underline how the company has watched real-world charging habits fall short of expectations. In that reporting, Mary Barra is quoted warning that if owners do not plug them in, the vehicles cannot deliver the promised efficiency. I read that as a rare acknowledgment from a major automaker that consumer habits, not just battery chemistry or charging infrastructure, can make or break a climate technology.

Why regulators and automakers leaned so hard on plug-in hybrids

To understand why Barra’s comments land with such force, it helps to remember how central plug-in hybrids have been to both corporate and government climate plans. For regulators, these vehicles offered a politically palatable compromise, allowing drivers to keep a gasoline safety net while still counting a large share of their miles as “electric” on paper. For automakers like GM, they were a way to meet tightening emissions rules without fully abandoning internal combustion platforms, since plug-in variants could be built on existing architectures.

That strategy depended on optimistic assumptions about how often owners would charge and how regulators would credit those electric miles. The “Mary Barra Admits” and “Fatal Flaw” framing now circulating in industry circles reflects a growing recognition that those assumptions were too generous. Emissions data showing that plug-in hybrids can pollute far more than expected when undercharged is forcing a rethink of how these vehicles are counted in fleet averages and how they are marketed to consumers. I see Barra’s remarks as a signal that even legacy manufacturers are preparing for a faster shift toward fully electric models, because the halfway solution is proving harder to defend.

What this means for drivers choosing their next car

For shoppers standing in a dealership lot, the debate over plug-in hybrids can feel abstract until it hits their own fuel bills and conscience. If a buyer has reliable access to home or workplace charging and is disciplined about plugging in, a plug-in hybrid can still deliver meaningful emissions cuts and lower running costs. The problem Barra is flagging is that many owners do not live that way, whether because they lack a driveway, share chargers in an apartment garage, or simply do not want another device to remember to charge every night.

That is why I see her “fatal flaw” comment as a consumer warning as much as an industry confession. Drivers who cannot realistically commit to frequent charging may be better served by either a highly efficient conventional hybrid or a fully electric vehicle that forces the charging habit by design. The reporting that ties together “Mary Barra Admits,” “Plug,” “In Hybrids,” and “Emissions Data Proves It” makes clear that the climate case for plug-in hybrids is conditional, not automatic, and that the burden of making them work falls heavily on the owner. For anyone weighing their next purchase, the lesson is straightforward: the badge on the trunk matters less than how, and how often, the car is actually plugged in.

More from Morning Overview