Physicists have long chased two of the biggest prizes in science: a practical fusion power plant and a clear detection of dark matter. Now a new line of research argues those quests might intersect, with future fusion reactors potentially acting as factories for exotic particles that help explain the invisible mass shaping the cosmos. If that idea holds up, the same machines built to decarbonize the grid could double as precision tools for probing the deepest gaps in modern physics.

The proposal is not science fiction. It grows out of detailed calculations of how high energy neutrons from fusion fuel would slam into the heavy metal walls of a reactor, occasionally producing hypothetical particles that slip through ordinary matter almost unnoticed. I see this as a rare case where an engineering challenge, the harsh environment inside a fusion device, becomes an opportunity to test bold theories about what dark matter might be made of.

Why dark matter still haunts modern physics

Dark matter sits at the center of this story because it remains the most glaring hole in the otherwise successful picture of the universe. Astronomers infer that some unseen substance outweighs normal matter by roughly a factor of five, yet it does not shine, absorb, or scatter light in any detectable way, which is why Dark matter earned its name. Its presence is revealed instead through gravity, from the way galaxies rotate to how clusters of galaxies bend the paths of background light. Those gravitational fingerprints are so consistent that most cosmologists now treat dark matter as a given, even if its microscopic identity is still unknown.

For decades, the leading candidates have been new kinds of particles that barely interact with the familiar protons, neutrons, and electrons that make up stars and people. One popular idea, highlighted by the Department of Energy, is that dark matter could consist of so called weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs, with masses between 1 and 1,000 times that of a proton. Another class of candidates, known as axions, would be much lighter but similarly elusive. Despite extensive searches in underground detectors and at particle colliders, no unambiguous signal has emerged, which is why any new environment that might produce or reveal such particles is drawing intense interest.

How fusion reactors work, and why their walls matter

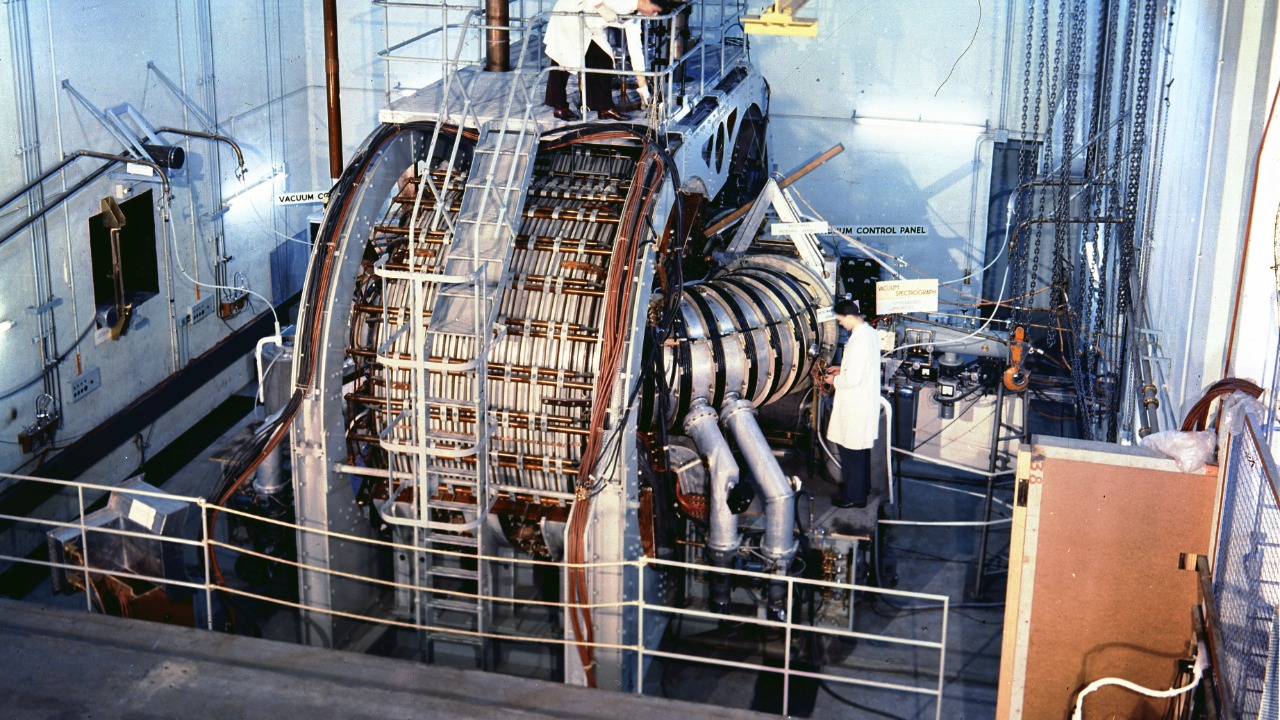

To understand why fusion devices are suddenly part of the dark matter conversation, it helps to look at how these reactors are designed. The most mature concepts rely on fusing deuterium and tritium, two heavy forms of hydrogen, inside a hot plasma that reaches temperatures hotter than the Sun. In the scenario analyzed by Zupan and his collaborators, that plasma sits inside a doughnut shaped chamber surrounded by a thick shell of materials like lead and tungsten. This shell, often called a breeding blanket, is engineered so that the high energy neutrons produced by fusion reactions strike lithium and generate fresh tritium fuel, allowing the reactor to sustain its own fuel cycle.

Those neutrons do not just make more fuel, they also batter the surrounding structure, creating a harsh radiation environment that engineers usually treat as a problem to be minimized. The new work flips that perspective, arguing that the same neutron rich conditions inside the blanket and walls could be fertile ground for producing exotic particles that resemble dark matter. In particular, the calculations suggest that when neutrons collide with heavy nuclei in the wall, they could occasionally emit hypothetical scalar particles that slip out of the reactor almost unnoticed, a possibility that earlier Dec analyses had only sketched in broad terms.

The new theory: exotic scalars born in the blanket

The heart of the proposal is a specific model of new physics that introduces what theorists call exotic scalar particles, a technical way of saying new fields that, like the Higgs boson, have no spin. In the study summarized in a recent Journal release, the team examined how such scalars could couple to both neutrons and the heavy elements in a fusion blanket. They showed that when a fast neutron from a deuterium tritium reaction hits a nucleus of lead or tungsten, there is a small but calculable chance that the interaction will radiate one of these scalars, which then streams out of the wall instead of depositing its energy locally. Because the scalars interact only feebly with ordinary matter, they behave much like dark matter candidates, passing through detectors and shielding with ease.

What makes this more than a mathematical curiosity is that the same interactions that would let the scalars escape a reactor also allow them to influence the early universe. The authors connected their reactor calculations to cosmological models, arguing that the same parameters that govern scalar production in a breeding blanket could also set the relic abundance of such particles after the Big Bang. That link is encoded in a detailed equation that, as one of the researchers joked in a Researchers summary, has many layers to the jokes but also many layers of physical insight. If future experiments can measure or constrain scalar production in reactors, they could therefore feed directly into our understanding of how much of the universe might be made of such particles.

From “Big Bang Theory” to Big Bang physics

The theoretical work did not emerge in a vacuum. It is part of a broader push to use creative analogies and pop culture hooks to communicate dense ideas in particle physics. In a playful twist highlighted in the Journal of High Energy Physics coverage, the authors titled their paper “Searching for exotic scalar particles in fusion reactors,” a nod that let them riff on sitcom references while still delivering a serious calculation. The formal citation, with DOI 10.1007 and article number 215, anchors the work in the peer reviewed literature, but the underlying message is straightforward: fusion machines are not just engineering projects, they are laboratories for fundamental physics.

That dual identity matters because it can attract different communities to the same hardware. Plasma physicists and engineers focus on keeping the reactor stable and efficient, while particle theorists look at the same neutron flux and see a potential beamline for new particles. In their technical write up, the team showed that the parameter space where these exotic scalars could be produced in detectable numbers is not yet ruled out by collider data or astrophysical observations, which is why they argue that fusion devices offer a fresh testing ground. By embedding their proposal in a rigorous 10.1007 style analysis, they aim to make sure the idea is taken seriously by both communities.

Why the walls are the new frontier for dark matter searches

Most dark matter experiments try to shield themselves from radiation, burying detectors deep underground to avoid stray cosmic rays and natural radioactivity. The fusion based proposal turns that logic on its head by embracing a noisy, high radiation environment and then looking for subtle deviations from what standard physics predicts. According to a detailed breakdown of how Fusion reactors may create dark matter particles in their walls, the key is that the breeding blanket and surrounding structures are thick enough to absorb almost all conventional radiation. If any energy appears to leak out in ways that cannot be explained by neutrons, gamma rays, or heat, it could hint at exotic particles carrying energy away.

In practice, that means instrumenting the reactor environment with sensitive monitors that track neutron fluxes, gamma emissions, and temperature gradients with high precision. The theory predicts that exotic scalar production would slightly alter the expected balance of these signals, especially in regions where neutrons are most likely to hit heavy nuclei. Researchers suggest that by comparing detailed simulations of neutron transport with real world measurements, they could infer whether additional invisible channels are at work. This strategy, outlined in a Dec focused analysis, would not require building entirely new machines, only adding targeted diagnostics to reactors that are already planned for energy research.

How this fits into the wider dark matter landscape

Even if fusion reactors can produce exotic scalars or similar particles, that does not automatically prove they make up the dark matter in the cosmos. The broader landscape of theories still includes WIMPs, axions, and other candidates that might never show up in a fusion environment. A recent overview from the University of Cincinnati emphasized that Dark matter is called dark precisely because it does not absorb or reflect light, and that, nevertheless, physicists have built a web of indirect evidence for its existence from galaxy rotation curves, gravitational lensing, and the cosmic microwave background. Fusion based searches would add one more thread to that web, probing a different combination of energies and interaction strengths than underground detectors or colliders.

Other reports, including a synthesis that began From The University of Cincinnati, stress that dark matter and dark energy together account for most of the mass energy content of the universe, while ordinary matter makes up only a small fraction. From The perspective of cosmology, any laboratory hint of new weakly interacting particles is therefore precious, even if it turns out that only a subset of them contribute to the cosmic budget. I see fusion reactors as complementary to, not replacements for, existing searches: they probe how new particles behave in dense, hot, neutron rich matter, a regime that is hard to reproduce elsewhere and that might mirror conditions in stellar interiors or supernovae where dark sector physics could also play a role.

Axions, WIMPs, and the competition for attention

The fusion scalar proposal arrives in a crowded field of dark matter ideas, each with its own experimental strategies. Axions, for example, are a leading hypothesis for very light dark matter that could be detected by converting them into photons in strong magnetic fields. A recent explainer noted that Axions and other light particles interact so weakly with ordinary matter that both have long been candidates for new physics beyond the Standard Model. WIMPs, by contrast, are heavier and are typically hunted through nuclear recoils in large underground tanks of xenon or argon, or through missing energy signatures at colliders like the Large Hadron Collider. Each class of candidate occupies a different region of mass and interaction strength, and no single experiment can cover them all.

Fusion reactors naturally favor scenarios where new particles couple to neutrons and heavy nuclei at energies comparable to those in deuterium tritium reactions. That makes them less sensitive to ultralight axions and more attuned to intermediate mass scalars or similar states. In that sense, the proposal carves out a niche in parameter space that has not been thoroughly explored by other methods. It also underscores a broader lesson: the hunt for dark matter is increasingly multi pronged, with experiments ranging from tabletop setups to astrophysical surveys and now, potentially, power plant scale fusion devices. If any of these efforts finds a convincing signal, the others will quickly pivot to test and refine the emerging picture.

What it would take to turn reactors into detectors

Turning a fusion power plant into a dark matter observatory is not as simple as flipping a switch. It would require careful coordination between reactor designers, nuclear engineers, and particle physicists to ensure that the necessary diagnostics are built in from the start. The study by Dec collaborators outlines a few concrete steps: placing neutron and gamma detectors at strategic locations around the blanket, designing segments of the wall with well characterized compositions to reduce uncertainties, and running detailed simulations of neutron transport that can be compared with measurements. They also emphasize the importance of long, stable runs, since the predicted signals are small and require good statistics to tease out.

There are practical challenges. Fusion reactors are already complex machines, with tight budgets and strict safety requirements, and adding experimental hardware could complicate operations. Yet there is precedent for dual use facilities: particle accelerators routinely host both applied and fundamental experiments, and even commercial nuclear reactors have been used to study neutrinos. Advocates of the fusion dark matter program argue that the incremental cost of adding a few specialized detectors is small compared with the potential scientific payoff. If the machines that power cities can also help answer what the universe is made of, the case for investing in them becomes even stronger.

Why this matters for the future of fusion and cosmology

For fusion research, the dark matter angle offers more than just a public relations boost. It reframes reactors as platforms for discovery, not just tools for energy production, which can attract talent and funding from communities that might otherwise stay focused on colliders or space missions. The idea that Dec researchers say fusion reactors might create particles linked to dark matter in their walls hints at a future where every major fusion facility has a parallel program in fundamental physics. That could accelerate innovation on both fronts, as improvements in diagnostics and modeling feed back into better reactor performance and sharper tests of new theories.

For cosmology and particle physics, the proposal is a reminder that nature often reveals itself in unexpected places. The same neutrons that engineers worry will damage reactor components might also be the key to producing and studying particles that have shaped the universe since its earliest moments. I find that prospect compelling: it suggests that solving our most practical energy challenges and our most abstract scientific puzzles are not separate projects, but intertwined chapters of the same story. If fusion reactors do end up forging dark sector particles, they will not just light our cities, they will illuminate the dark corners of the cosmos that have puzzled scientists for generations.

More from MorningOverview