Fusion startups are racing to prove that they can bottle the power of the stars without the sprawling magnets or precision particle beams that defined earlier generations of reactors. Instead of copying giant tokamaks, a new wave of companies is betting on self-organizing plasmas, projectile-driven compression, and laser-triggered reactions that promise simpler machines and cheaper power plants. The claims are bold, and the physics is unforgiving, but the shift away from magnets and beams is already reshaping how investors and researchers think about commercial fusion.

At stake is whether fusion can move from billion‑dollar science projects to compact generators that slot into real power grids. If these alternative concepts work, they could sidestep some of the hardest engineering problems in magnetic confinement and inertial confinement, while opening the door to fuels that are cleaner and easier to handle than the deuterium‑tritium mix used in most government programs. I see a field that is still far from net electricity, yet increasingly confident that magnets and beams are no longer the only viable tools for taming fusion plasmas.

The startup pivot away from giant magnets

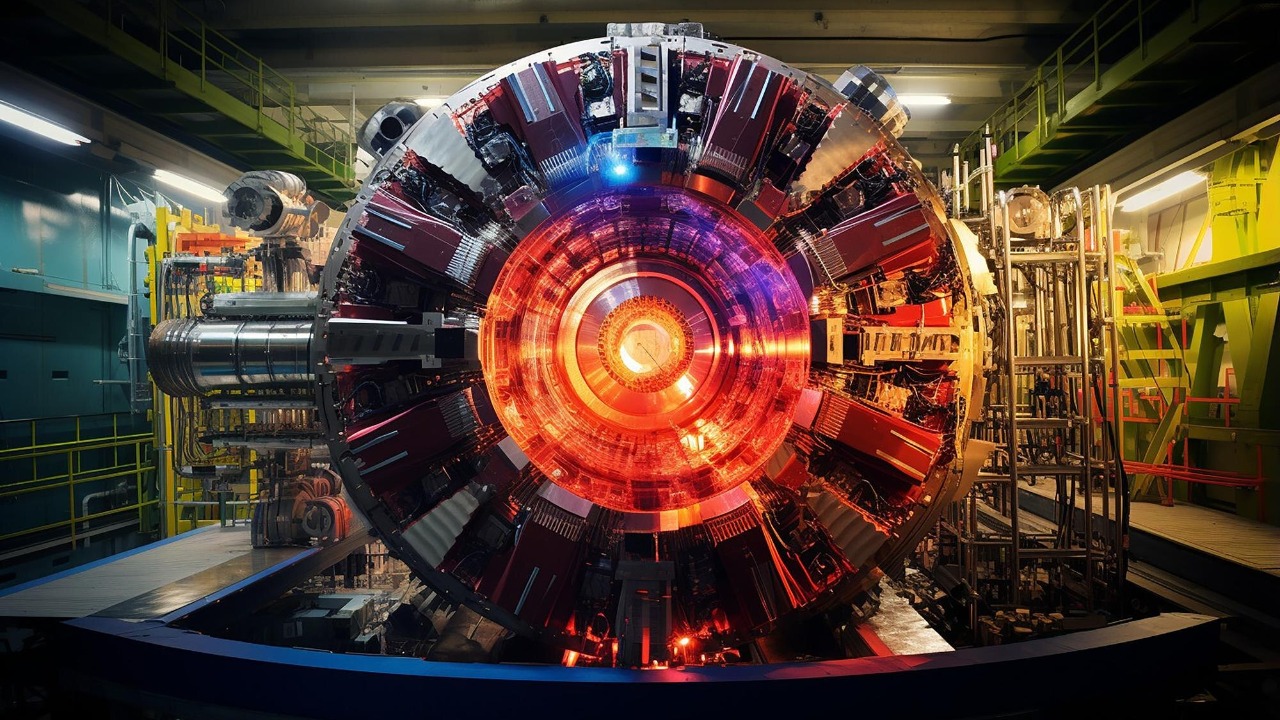

For decades, fusion research was dominated by tokamaks and stellarators, machines that rely on massive superconducting magnets to corral a doughnut of plasma. That approach produced impressive scientific milestones but also sprawling facilities and eye‑watering costs, which left plenty of room for smaller players to argue that a different path might reach the grid faster. A growing ecosystem of fusion startups is now pursuing compact devices that either use much smaller magnetic systems or try to avoid large external magnets altogether, a shift that has attracted private capital and fresh engineering talent into what was once a purely public‑sector domain, as documented in surveys of fusion startups.

These companies are not just shrinking existing designs, they are rethinking the core physics of confinement and energy capture. Some are exploring magnetized target fusion, where a modest magnetic field is combined with mechanical compression, while others are betting on aneutronic fuels that could allow direct conversion of charged particles into electricity. The common thread is a desire to simplify the hardware compared with the intricate coils and cryogenic systems that define traditional reactors, and to turn fusion from a bespoke experiment into something that looks more like a scalable energy product.

Field-reversed configurations and “self-made” magnetic bottles

One of the most striking claims that magnets can be minimized comes from companies working with field‑reversed configurations, or FRCs, which confine plasma in a compact, linear geometry rather than a torus. In this approach, the plasma itself generates much of the magnetic field needed to hold it together, reducing the burden on external coils and power supplies. An FRC plasma self‑organizes and creates its own magnetic field inside the machine, a behavior that allows the device to operate with a simpler set of external magnets and potentially lower construction and operating costs, according to technical descriptions of An FRC.

Companies pursuing this route argue that a linear FRC machine can be much less complicated to construct than a toroidal reactor, with fewer components that must be aligned and cooled to extreme temperatures. One prominent developer describes its device as a simpler, linear fusion machine that is less costly to build and run and easier to maintain, in part because it avoids the complex and costly plasma formation systems associated with traditional designs, a point underscored in its explanation of how one way to cut costs is to let the plasma shoulder more of the confinement work. I see this as a hybrid vision rather than a total rejection of magnets, but it clearly shifts the balance from heavy external hardware to the plasma’s own self‑organization.

Hydrogen-boron fusion and the quest for aneutronic power

Alongside new confinement schemes, several startups are chasing hydrogen‑boron, or p‑B11, reactions that promise cleaner fusion with fewer neutrons and less radioactive waste. In this fuel cycle, protons fuse with boron‑11 to produce three alpha particles, which are charged and can in principle be converted directly into electricity without the intermediate step of boiling water. Advocates highlight that hydrogen‑boron reactions use fuels that are safe and abundant and do not create neutrons in the primary reaction, so they cause insignificant activation of reactor materials compared with deuterium‑tritium systems, a key selling point emphasized in reports on hydrogen‑boron experiments.

Hydrogen‑boron fusion is notoriously difficult to ignite, since it requires higher temperatures and more precise control than deuterium‑tritium, but recent experiments have started to chip away at that barrier. One program reported that its hydrogen‑boron work did not yet produce net energy, but it demonstrated the viability of aneutronic fusion and set the stage for future attempts to reach net energy from its technology, according to a detailed account of a milestone in this field. I read these results as early but important signals that cleaner fuels can be paired with alternative confinement schemes, including FRCs, to build reactors that are not only simpler on the outside but also gentler on the materials inside.

Lasers, projectiles, and fusion without beams

Another front in the move away from magnets and beams is laser‑driven fusion, where high‑power pulses compress and heat fuel pellets to fusion conditions. One company working on hydrogen‑boron has demonstrated fusion using high‑power lasers, positioning its approach as a path toward the so‑called holy grail of clean energy by combining aneutronic fuel with optical drivers instead of particle beams. In that setup, the lasers trigger the reaction in a small target, and the resulting alpha particles could in principle be harvested through direct conversion, a concept that underpins HB11’s proposed direct conversion scheme.

Beyond lasers, some startups are experimenting with projectile‑based inertial confinement, where a physical impactor slams into a target to compress it instead of relying on a bank of lasers or ion beams. First Light Fusion is a private company innovating in inertial confinement fusion that uses a unique projectile‑based approach to achieve the necessary compression, pitching this as a potentially more efficient and more affordable path to fusion energy than traditional beam‑driven schemes, as outlined in profiles of First Light Fusion. I see these efforts as part of a broader trend to replace complex driver systems with mechanical or optical tools that are easier to scale and maintain, even if they introduce their own engineering challenges in target fabrication and repetition rate.

From lab breakthroughs to grid-scale reality

Even as these alternative concepts gain momentum, the gap between experimental breakthroughs and commercial power plants remains wide. Many of the most ambitious claims about eliminating magnets or beams still rely on sophisticated control systems, high‑voltage pulsed power, or precision optics that are not trivial to industrialize. Established fusion researchers, including figures like Dennis Whyte, have argued that any credible path to fusion must grapple with materials, maintenance, and integration into real grids, not just headline‑grabbing confinement tricks, a perspective that runs through in‑depth reporting on Dennis Whyte’s work.

At the same time, the influx of private capital and the diversity of designs are forcing the field to confront practical questions earlier in the development cycle. Startups are under pressure to show not only that their plasmas can reach fusion conditions, but also that their machines can be manufactured, serviced, and financed at scale, a reality that is reshaping how fusion research is organized. I see the current wave of “no magnets, no beams” rhetoric as a useful provocation rather than a settled verdict: it pushes the community to simplify and innovate, while the hard work of proving net electricity and long‑term reliability still lies ahead.

More from Morning Overview