Plasma is usually introduced as the stuff of stars and fusion reactors, a searing soup of charged particles that has little in common with the ice in a household freezer. Yet new experiments show that when plasma meets ultracold water vapor, it can grow delicate, electrically active frost that behaves in ways classic plasma theory does not predict. Those fluffy charged ice grains are now opening a window on “icy hot” regimes that link laboratory physics to the hidden chemistry of comets, planetary rings, and interstellar clouds.

Instead of treating ice as a passive contaminant, researchers are turning it into a diagnostic tool, using its fractal growth and motion to reveal how charged grains and gas interact in extreme environments. I see this as a rare case where something that looks almost whimsical under the microscope, a lacy snowflake floating in a glow of ionized gas, is quietly rewriting how scientists think about the forces that shape matter across the galaxy.

Plasma meets frost: why “icy hot” matters

At first glance, combining a fiery plasma with frigid ice sounds like a recipe for instant evaporation, not a new branch of physics. Yet the latest work on fluffy, electrically charged ice grains shows that when cold gas is threaded by electric fields, it can host plasma that coexists with, and even nurtures, fragile frozen structures. In these experiments, the plasma does not simply melt the ice, it helps assemble it into intricate, fractal grains that carry charge and respond to electromagnetic forces in ways that challenge standard models of dusty plasmas.

The stakes go far beyond a clever laboratory trick. Many of the most intriguing regions in space, from the halos of comets to the rings of Saturn, are mixtures of cold gas, dust, and ionized particles that behave neither like a simple solid nor a conventional plasma. By watching how these fluffy grains grow and move inside controlled “icy hot” plasmas, researchers can probe how charged particles drag neutral gas, how grains exchange charge, and how they might help drive flows of gas and dust across astrophysical environments, as described in detailed reports on new plasma dynamics.

Inside the Caltech experiment: building a frosty plasma

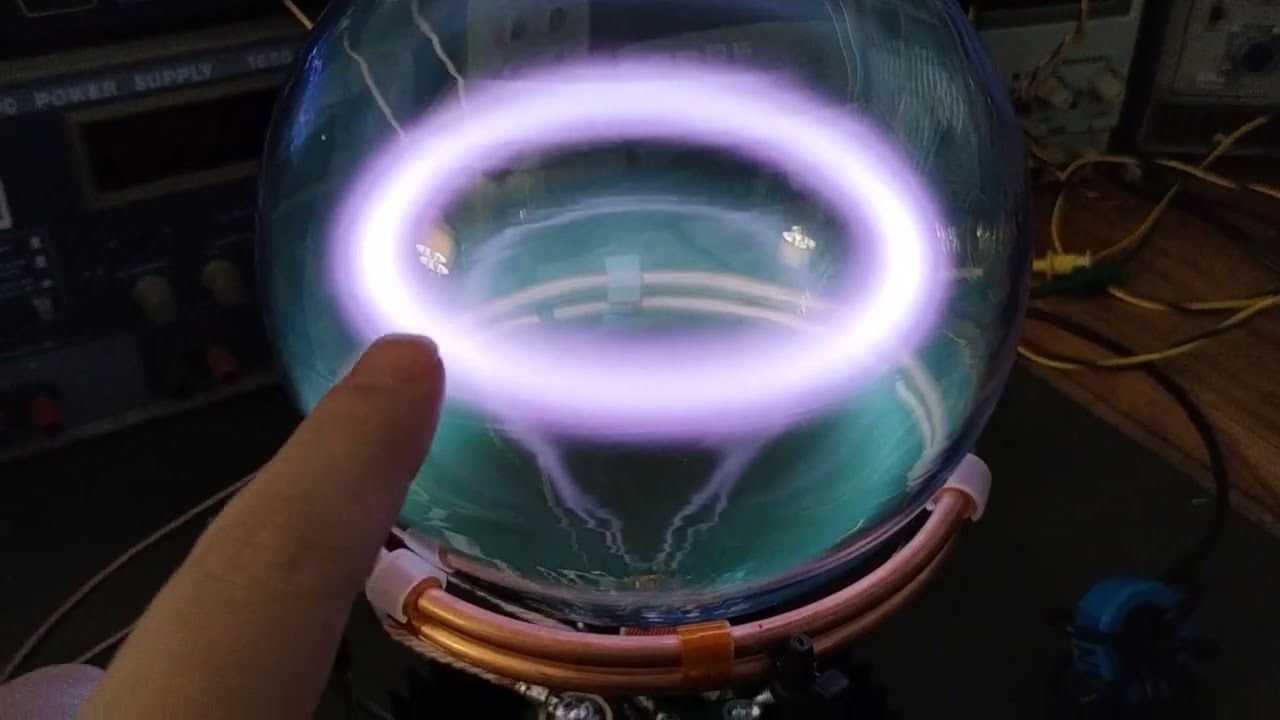

To get beyond theory, physicists needed a way to actually grow ice inside a plasma without destroying it. At Caltech, researchers created that unlikely combination by starting with a neutral gas chilled to the point where water vapor could freeze, then zapping it between frosty electrodes to ignite a glow of ionized particles. The key was to keep the overall environment cold enough that water molecules condensed into solid grains even as electrons and ions streamed through the gas, turning the chamber into a kind of electrified freezer where plasma and frost cohabited.

Once the basic plasma was established, the team introduced controlled amounts of water vapor and watched as it condensed into tiny seeds that rapidly branched into complex, fractal structures. These grains did not resemble compact hailstones, they looked more like lacy snowflakes or tangled frost, with large surface areas and low densities that made them exceptionally responsive to electric fields. A social media summary of the work captured the essence of this setup, noting how Caltech physicists created plasma by zapping a chilly neutral gas between frosty electrodes and how adding water vapor caused “fractal frost” to grow while interacting with neutral gases, a description that matches the experimental approach highlighted in the Fractal Frost in Fiery Fields thread.

Fluffy, fractal grains that refuse to behave

What makes these ice grains so revealing is not just that they exist inside a plasma, but that they grow into fractal, highly porous shapes that defy the assumptions built into many plasma models. Traditional dusty plasma theory often treats grains as compact spheres with well-defined sizes and charges, a simplification that works reasonably well for solid particles like silicate dust. In the Caltech experiments, the grains instead developed branching, tree-like structures that increased their effective cross section and changed how they collected charge, making them “fluffy” in both geometry and dynamics.

Understanding the fractal growth and motion of these grains within plasma systems is not an aesthetic exercise, it could improve strategies for controlling or predicting how charged dust behaves in fusion devices, industrial reactors, and astrophysical settings. The experiments show that even as the grains grow to relatively large sizes, hundreds of times larger than the solid plasma dust typically studied, they remain strongly coupled to the surrounding electric fields and gas flows. That remained true even of ice grains that grew to relatively large sizes, hundreds of times larger than the solid plasma dust, a point emphasized in follow up analyses that connect this behavior to gas and dust streaming across the galaxy, as detailed in a focused section on fractal growth and motion.

Charging up the ice: how grains become tiny plasma antennas

For ice grains to matter in plasma physics, they have to do more than float, they must carry charge and interact with fields. In the “icy hot” experiments, electrons and ions from the plasma continually collided with the growing frost, leaving the grains with net electric charges that could be surprisingly large relative to their mass. Because the grains were so fluffy, with many protruding branches, they offered abundant surface area for charge collection, turning each one into a kind of miniature antenna that sensed and responded to the local plasma environment.

Once charged, the grains experienced forces from electric fields in the plasma that could accelerate them, align them, or even cause them to cluster in regions where fields and gas flows converged. This behavior is crucial for understanding how similarly charged fluffy grains interact in astrophysical environments, where they might repel each other at short range yet still move together under the influence of large scale fields. One analysis notes that Bellan, a key figure in the work, has argued that this behavior might help explain how similarly charged fluffy grains interact in astrophysical environments, highlighting the role of charge in mediating grain dynamics and pointing to broader implications captured in a summary of electrically charged ice grains.

From lab chamber to galaxy: why the grains matter in space

It is tempting to treat these experiments as a curiosity confined to a vacuum chamber, but the physics they reveal maps directly onto some of the most dynamic regions in space. In astrophysical environments, cold gas, dust, and plasma coexist in complex mixtures that are notoriously hard to model, from the tenuous clouds between stars to the dense comae of comets. The fluffy, charged ice grains grown in the lab are analogues for the icy dust that forms in these regions, and their behavior hints at how such grains might help move material around on cosmic scales.

One of the most striking claims emerging from the work is that the tiny fluffy grains might even be responsible for gas and dust streaming across the galaxy, by coupling neutral material to large scale electromagnetic fields and dragging it along. In this picture, the grains act as intermediaries, picking up charge from the plasma, feeling the electromagnetic forces, and then transferring momentum to the surrounding neutral gas through collisions. Reports on electrified ice grains emphasize that these tiny fluffy grains, therefore, might even be responsible for gas and dust streaming across the galaxy, underscoring the potential reach of the laboratory findings and their connection to gas and dust streaming.

Astrophysical echoes: comets, rings, and prebiotic cargo

Once you accept that fluffy, charged ice grains can steer gas and dust, a range of astrophysical puzzles start to look different. In cometary comae, for example, sunlight and solar wind particles ionize gas around the nucleus, while jets of water vapor and dust erupt from the surface. If that dust includes fractal, icy grains similar to those grown in the lab, then their charging and motion could help explain the complex tails and jets seen in missions like ESA’s Rosetta, where neutral gas and plasma appeared tightly coupled over large distances.

There is also a chemical dimension. Icy grains in comets and protoplanetary disks are thought to carry prebiotic material, including organic molecules that might seed young planets. If those grains are fluffy and highly charged, their trajectories through disks and planetary systems could determine where that material ends up, concentrating it in some regions and depleting it in others. A concise social media summary of the Caltech work notes that the “Icy Hot Plasmas, Fluffy, Electrically Charged Ice Grains Reveal New Plasma Dynamics” experiments connect directly to how such grains might carry prebiotic material in comets, a link that underscores the astrobiological stakes and is highlighted in the discussion of prebiotic material in comets.

Challenging textbook plasma physics

For decades, plasma physics textbooks have leaned on idealized pictures of ionized gases, often treating dust and grains as small perturbations that can be folded into existing equations. The behavior of fluffy, fractal ice grains in “icy hot” plasmas suggests that this hierarchy may need to be inverted in some regimes, with the grains taking center stage as active players that shape fields and flows. When grains grow to hundreds of times the size of typical solid plasma dust yet remain tightly coupled to the plasma, they can dominate momentum exchange and energy dissipation, forcing theorists to rethink how they model dusty plasmas in both labs and space.

That shift is not purely conceptual, it has practical consequences for how scientists interpret observations and design experiments. If grain geometry and fluffiness strongly influence charging and motion, then models that assume compact spheres may misestimate how quickly dust settles in fusion devices, how efficiently it is transported in industrial reactors, or how it migrates in protoplanetary disks. Detailed write ups of the Caltech work stress that understanding the fractal growth and motion of grains within plasma systems could improve strategies for controlling or predicting these behaviors, and they highlight that this remained true even of ice grains that grew to relatively large sizes, hundreds of times larger than the solid plasma dust, a point reiterated in a broader overview of icy hot plasma behavior.

From fusion labs to semiconductor fabs

Although the imagery of frosty grains in glowing plasma naturally evokes space, the same physics could matter in some of the most terrestrial technologies. In magnetic confinement fusion devices, for instance, dust and flakes from reactor walls can enter the plasma, affecting performance and potentially damaging components. If those particles pick up volatile coatings or form porous structures under certain conditions, their charging and motion might resemble the fluffy grains in the Caltech experiments more than the compact spheres assumed in many models, with implications for how engineers design dust mitigation systems.

Industrial plasma reactors used in semiconductor fabrication and materials processing also operate in regimes where neutral gases, condensable vapors, and ionized particles mix. In extreme ultraviolet lithography tools, for example, tin droplets are vaporized and ionized to produce light, while residual gases and contaminants can condense on surfaces. If future processes involve colder plasmas or intentional introduction of condensable species, understanding how fractal grains grow and move could help prevent unwanted particle contamination or, conversely, enable new self-assembled nanostructures. The broader reporting on these experiments notes that understanding the fractal growth and motion of grains within plasma systems could improve strategies for controlling or predicting behavior in such applied settings, a theme that aligns with the emphasis on controlling grain behavior in complex plasmas.

Decoding the “Dec” details and the road ahead

One of the quirks of following this story through its various reports and summaries is the repeated appearance of the shorthand “Dec” alongside key phrases like “Icy” and “Fluffy,” a reminder of how quickly the work has propagated across technical write ups and popular coverage. That repetition reflects how central those descriptors have become to the narrative, with “Icy” capturing the cold, condensable component, “Fluffy” evoking the fractal, low density structure of the grains, and “Dec” marking the period when the findings crystallized into a coherent picture of new plasma dynamics. The combination has turned what might have been a niche dusty plasma study into a recognizable reference point in discussions of how cold and hot phases of matter interact.

Looking ahead, the most interesting questions are less about whether the grains exist, that is now well established, and more about how far their influence extends. Do similar fluffy, charged structures form naturally in the upper atmospheres of icy moons, in the plumes of Enceladus, or in the dense rings of Saturn where plasma and ice coexist? Can controlled “icy hot” plasmas be engineered to assemble custom fractal materials on Earth, with tunable electrical and optical properties? The early coverage of these experiments, including summaries that highlight “Dec, Icy, Fluffy, Credit, California Institute of” as key identifiers, hints at a growing recognition that the physics of fluffy, electrically charged ice grains is not a curiosity but a new lens on plasma behavior, a point underscored in overviews of icy hot plasmas.

Why I think “fluffy ice” will stick in the plasma lexicon

As a reporter who has watched plasma physics stories come and go, I am struck by how quickly the language of “fluffy, electrically charged ice grains” has taken hold among researchers and communicators. Part of the appeal is visual, the idea of frost growing inside a glow discharge is inherently memorable, but there is also a conceptual clarity to it. The grains are fluffy, not in a casual sense, but in a precise, fractal way that affects how they interact with fields and gas, and they are icy and charged in a way that bridges the gap between cold astrophysical environments and hot laboratory plasmas.

That combination of vivid imagery and hard physics is likely to keep this work in circulation as more groups test and extend it. I expect to see “fluffy ice” used as a shorthand in conference talks and review papers for a class of grains that are neither compact dust nor simple ice crystals, but something in between that can steer gas and dust on scales from vacuum chambers to galaxies. The detailed institutional summaries that first framed these experiments as “Icy Hot Plasmas, Fluffy, Electrically Charged Ice Grains Reveal New Plasma Dynamics” have already seeded that vocabulary, and as more data accumulate, the phrase will probably become a standard reference point for this emerging corner of plasma physics, as reflected in the comprehensive overview of fluffy ice grain dynamics.

More from MorningOverview