Elon Musk’s humanoid robot project, Optimus, is being sold as the next general-purpose machine that will walk out of Tesla factories and into homes, warehouses and elder-care facilities. The pitch leans heavily on spectacle, from tap-dancing demos to slick factory footage, while sidestepping the harder conversation about what happens when a 100‑plus‑pound machine with networked sensors, opaque AI and humanlike reach goes wrong. The more Optimus is framed as inevitable progress, the more urgent it becomes to ask why the safety case is still a hazy afterthought rather than the core of the story.

What Musk is offering is not just another gadget but a new kind of infrastructure, a mobile robot that could share space with children, older adults and workers in already risky environments. That scale of ambition demands a level of transparency about failure modes, cybersecurity and human oversight that Tesla has not yet demonstrated in its vehicles, let alone in a bipedal robot. I see a widening gap between the hype cycle and the sober engineering and governance work that a technology like this actually requires.

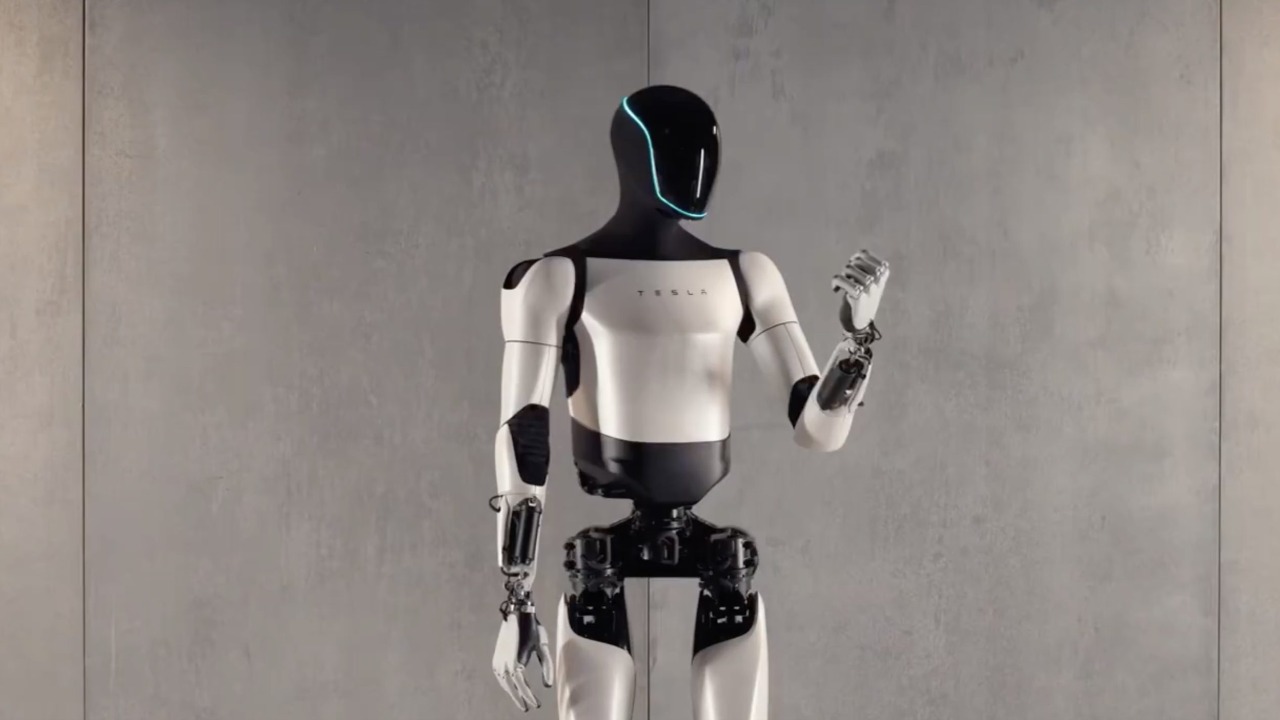

From Tesla Bot promise to Optimus reality

When Musk first introduced what he then called Tesla Bot, he framed it as a near-term extension of the company’s vehicle AI that could eventually replace human labor in repetitive or dangerous jobs. The concept was pitched as a kind of safety upgrade for society, a way to offload risk from people to machines that, in Musk’s telling, would be physically limited so a person could “most likely overpower it.” That reassurance sounds thinner now that Optimus is being positioned as a general-purpose worker that might roam factories and homes, where the line between “assistive” and “overpowering” is far less clear.

Robotics experts have warned that this leap from concept art to universal helper glosses over how brittle current AI systems remain in unstructured environments. In one detailed critique, specialists pointed out that the humanoid form factor itself introduces complex balance, perception and control challenges that Tesla has not solved in its cars, let alone in a walking machine, and they questioned whether the company’s data-driven approach can safely scale to a robot that shares space with people in close quarters. That skepticism, laid out in an analysis of Optimus, undercuts the idea that vehicle autonomy can simply be repackaged into a biped and dropped into workplaces without a fundamentally different safety regime.

Viral demos, suspicious tumbles and the illusion of competence

The public face of Optimus so far has been a series of tightly edited videos that showcase agility and charm rather than robustness. In one widely shared clip, the robot is seen Pulling off tap-dancing moves that most humans would struggle to match, a performance that Musk’s fans hailed as proof of rapid progress. Critics, however, noted how little the video revealed about what was preprogrammed, how many takes were discarded or how the system would behave outside a choreographed routine, and some observers described the display as a “creepy” glimpse of a dangerous invention dressed up as entertainment.

Other footage has been less flattering, including a recent demonstration in Miami where an Optimus unit took what looked like a suspiciously hard tumble in front of onlookers. A separate video posted in Dec showed the robot collapsing in a way that underscored how far it still is from the kind of precision and stability that industrial users expect from mature automation. These moments matter because they reveal a system that can fail abruptly and dramatically, yet the company’s messaging continues to emphasize showmanship over a clear accounting of how often Optimus falls, what damage those failures could cause and how the design mitigates harm when gravity wins.

Cybersecurity, sensors and the risk of hijacked bodies

Beyond mechanical stumbles, the most unsettling questions around Optimus involve what happens if its networked brain is compromised. Security researchers examining the robot’s architecture have warned that its reliance on cameras and other sensor inputs makes it vulnerable to adversarial attacks that subtly alter what it “sees.” In Tesla’s own Optimus environment, they note that an attacker could tweak a visual marker or feed a manipulated sensor readout so the robot misidentifies a person as an object, or ignores a crucial safety warning, all without tripping conventional alarms. That is not a theoretical nuisance when the machine in question can lift heavy loads or operate near fragile human bodies.

Another analysis of remote threats highlights Optimus as a contemporary humanoid robot developed by Tesla for dangerous and monotonous work, and then asks what happens if that same connectivity is turned against it. The authors describe One scenario in which a remote hijacker could seize control of an Optimus unit and repurpose it as a physical attack tool or a surveillance device, exploiting the same network pathways that enable over-the-air updates and fleet learning. The idea that a robot built by Tesla Robots could be turned into a weapon by a distant adversary is not science fiction, it is a foreseeable misuse that should be front and center in any responsible rollout plan, yet Musk’s public comments tend to skate past these possibilities in favor of grand promises about productivity.

Opaque AI, Muskworld and the problem of accountability

Underneath the glossy videos and cybersecurity warnings lies a deeper issue: how little anyone outside Tesla knows about how Optimus makes decisions or how those decisions can be audited when something goes wrong. One seasoned technologist described the broader pattern as a retreat into “Muskworld,” a space where systems are trained on vast amounts of data until they appear to work, but when they fail, it is hard to understand why or to fix the underlying problem. In that critique, the author notes that But when these opaque models fail, engineers often cannot easily trace what went wrong, which is a direct hit to safety in any system that interacts with the physical world.

The same discussion points out that sensors and microphones used for driver assistance can also be repurposed as listening devices, raising questions about how much ambient data a company like Tesla quietly collects and how it might be used. If Optimus inherits that philosophy, it will not just be a worker in a factory or a helper in a home, it will be a rolling node in a surveillance network whose behavior is governed by code that outsiders cannot inspect. That combination of opacity and reach is why I see the current hype as so troubling: it normalizes the idea that a private company can deploy legions of semi-autonomous machines into public and private spaces without first submitting their AI and data practices to meaningful external scrutiny.

Public skepticism, aging users and the missing safety conversation

Outside the fan communities, there is already a visible backlash against what some see as Musk’s habit of overpromising on autonomy. In a Cybertruck owners group, one discussion about self-driving features for older drivers framed the technology as “HOPE” for people who grew up with a Chevy from 56, only to be met with a sharp reminder that this is “More Elon Mus” hype used to prop up the stock price. That tension between hope and distrust will only intensify if Optimus is marketed as a solution for elder care or disability support, where the margin for error is even smaller than in a pickup truck.

More from Morning Overview