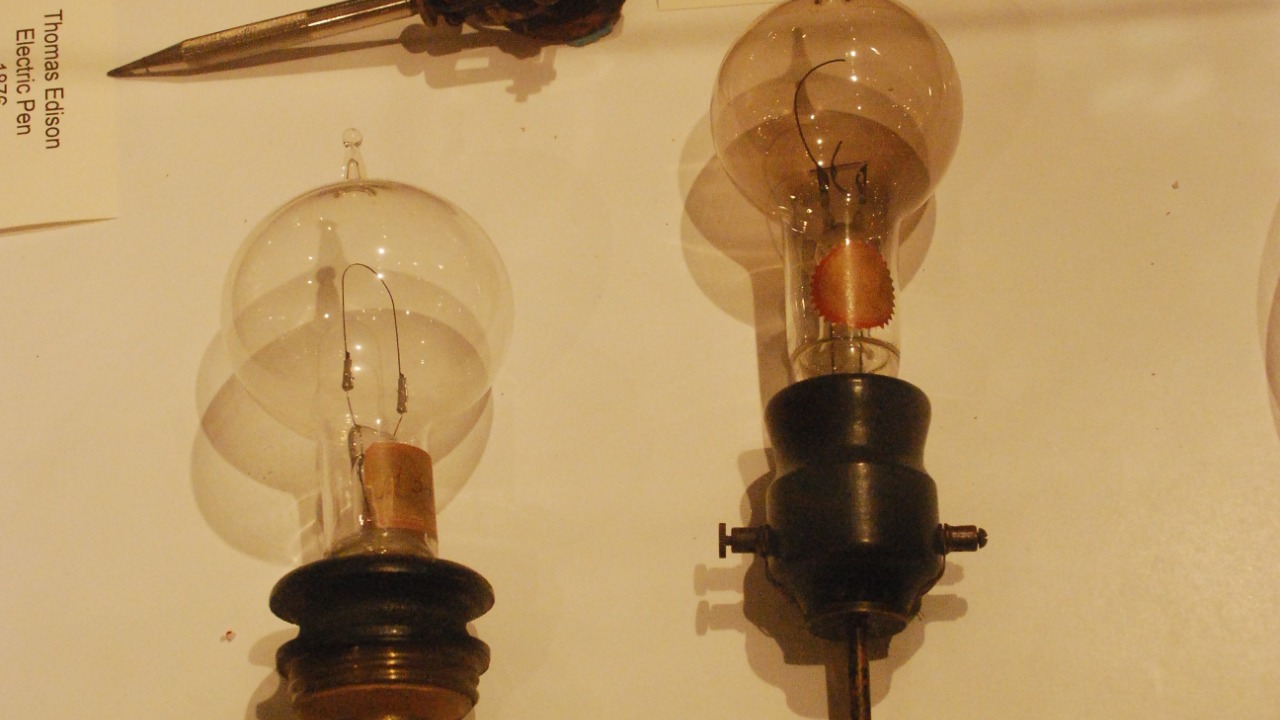

When Thomas Alva Edison was painstakingly testing carbonized filaments for his early light bulbs in 1879, he was chasing a practical, long‑lasting glow, not a new form of matter. Yet new laboratory work suggests those same experiments may have produced graphene, the atom‑thin carbon material that would not be formally identified for more than a century. If that interpretation holds, one of the most hyped “wonder materials” of modern physics may have been hiding in plain sight inside Edison’s glass bulbs.

The idea does not rewrite who discovered graphene as a concept, but it does reframe how far back its physical traces might go. By retracing Edison’s steps with modern instruments, chemists now argue that his carbon filaments likely contained microscopic patches of graphene that helped them survive the brutal conditions inside the lamp. In other words, the secret to Edison’s breakthrough in stable electric lighting may have rested on a material he could not possibly have named.

Recreating a 19th‑century lab with 21st‑century tools

The new work began with a simple question: what, exactly, was happening inside those early bulbs when Edison heated plant fibers until they glowed? To find out, a team of chemists at Rice University set out to replicate Thomas Edison’s seminal light bulb experiments as faithfully as possible, then probe the resulting filaments with techniques that did not exist in the nineteenth century. By rebuilding the old process in a modern lab, the researchers could watch how the carbon structure evolved instead of inferring it from brightness and lifetime alone.

According to reporting on the project, the Rice University chemists carefully reproduced the carbonization of natural fibers and the vacuum conditions Edison’s team used, then examined the filaments with high‑resolution imaging and spectroscopy. Their analysis pointed to the formation of thin, ordered carbon layers that match the hallmarks of graphene, suggesting that Edison’s push for a durable filament inadvertently created this advanced material as a byproduct. The researchers argue that the key to his success in stable electric lighting may lie in these hidden graphene regions, a conclusion detailed in coverage of the Rice University experiments.

Evidence that graphene really formed in Edison’s filaments

Claims about rediscovering graphene in century‑old technology demand more than a suggestive microscope image, so the Rice team backed their historical narrative with formal materials analysis. In a peer‑reviewed study titled “Evidence for Graphene Formation in Thomas Edison’s 1879 …,” the authors describe how they compared the carbonized filaments to known graphene samples and to other forms of carbon such as amorphous soot and graphite. The goal was to show that the filaments did not just contain generic carbon, but specific atomic arrangements consistent with graphene’s single‑layer hexagonal lattice.

The study’s abstract, which credits Thomas Alva Edison as an American inventor famous for his breakthroughs in stable electric lighting, reports spectroscopic signatures and structural patterns that align with graphene rather than bulk graphite. The researchers interpret these measurements as direct evidence that thin graphene domains formed within the carbonized plant fibers under Edison’s operating conditions, even though no one at the time had the language or tools to recognize them. That conclusion is laid out in the Abstract, which frames the work as a bridge between historical invention and modern nanoscience.

How Rice researchers say graphene emerged as a byproduct

To understand how graphene could appear in a nineteenth‑century bulb, it helps to look at the messy chemistry of Edison’s process. He and his assistants heated organic materials such as bamboo and cotton in low‑oxygen environments, driving off hydrogen and other elements until mostly carbon remained. Under the intense heat and electrical stress inside the bulb, parts of that carbon could reorganize into more ordered structures, especially along the surface of the filament where current density and temperature peaked.

The Rice team argues that under these conditions, thin layers of carbon atoms naturally settled into graphene‑like sheets, effectively coating or threading through the bulk filament. In their reconstruction, these sheets were not the goal but an unintentional byproduct that nonetheless improved performance by enhancing electrical conductivity and mechanical strength. Reporting on the project notes that Rice researchers replicating Edison’s 1879 light bulb experiments concluded that graphene may have been such an unintentional byproduct, a finding summarized in a Rice release that highlights how closely the modern setup followed Edison’s original methods.

What this means for the story of graphene

If Edison’s filaments did contain graphene, that does not erase the achievements of the scientists who isolated and named the material in the twenty‑first century. Instead, it suggests that graphene’s physical presence predates its conceptual discovery, much as X‑rays existed in every lightning storm long before Wilhelm Röntgen described them. The Rice work reframes graphene not as a sudden invention but as a recurring outcome of certain high‑temperature carbon processes, some of which were already central to industrial technology in the late 1800s.

For historians of science, this adds a new layer to the story of Thomas Alva Edison as an American inventor. His reputation has long rested on practical breakthroughs in stable electric lighting and the system that surrounded it, from generators to distribution networks. The possibility that his 1879 experiments also generated graphene, even unknowingly, underscores how much advanced physics can lie buried in historical experiments. It also hints that other nineteenth‑century devices that relied on carbon, from early microphones to arc lamps, may have harbored similar nanostructures that only modern tools can fully reveal.

Why revisiting old experiments still matters

Beyond the historical curiosity, I see a practical lesson in the Rice team’s decision to revisit Edison’s work with fresh eyes. Modern laboratories often chase entirely new materials or exotic fabrication methods, yet this project shows the value of interrogating classic experiments with updated instrumentation. By doing so, the chemists did not just confirm a textbook story about carbon filaments, they uncovered a plausible link between a Victorian workshop and one of today’s most studied nanomaterials.

That mindset could inspire similar re‑examinations of other foundational technologies, from the alloys in early railroad tracks to the chemistry of photographic plates. If graphene can emerge from a bamboo filament in an 1879 bulb, there may be other advanced structures hiding in the artifacts of industrial history, waiting for someone to look closely enough. Revisiting those systems with the rigor applied by the Rice University chemists, who retraced Edison’s steps in detail, offers a way to connect the ingenuity of past inventors with the analytical power of contemporary science.

More from Morning Overview