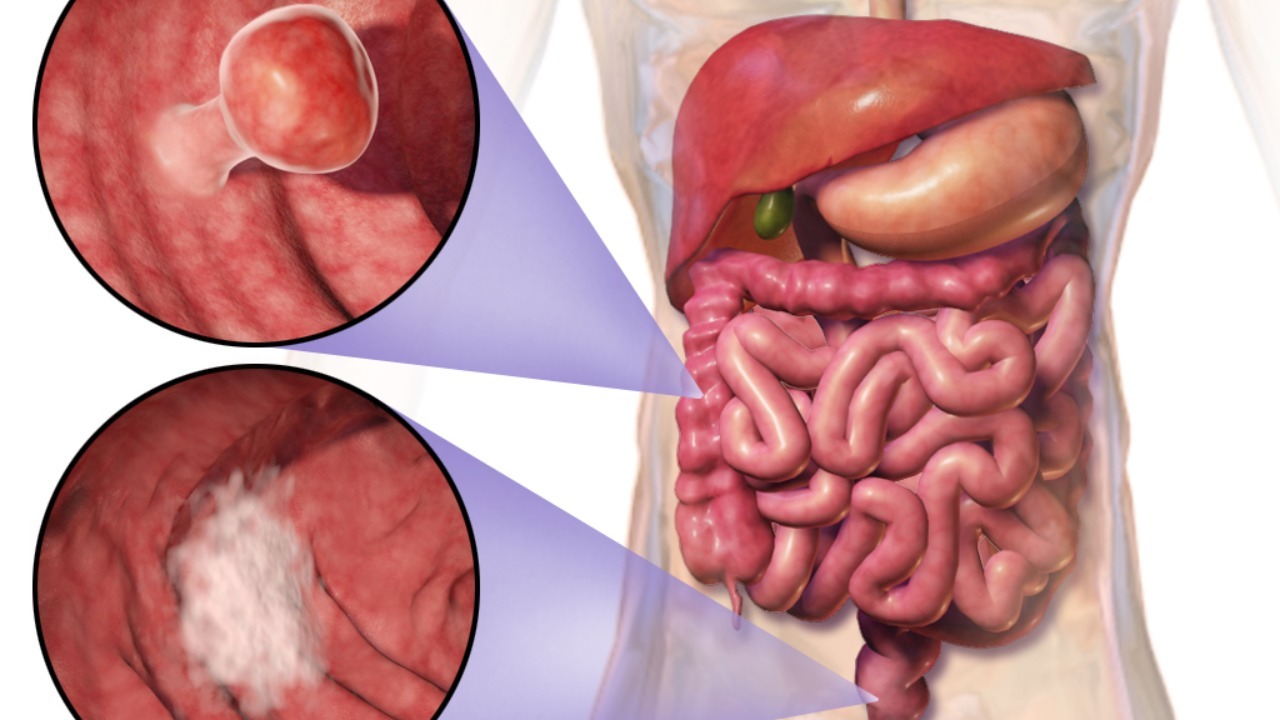

A lethal bacterium best known for causing cholera is now at the center of one of the most surprising cancer stories of the year. In laboratory models of colorectal cancer, a purified toxin from Vibrio cholerae has halted tumor growth and even shrunk established tumors while leaving surrounding tissue largely unscathed. The finding hints at a future in which a carefully engineered version of this toxin could turn one of medicine’s oldest foes into a precision weapon against one of its deadliest cancers.

Researchers in Umeå have focused on a single component of the cholera bacterium’s arsenal, a cytotoxin called MakA, and found that it not only attacks cancer cells directly but also appears to rally the immune system inside tumors. For a disease where standard chemotherapy can damage healthy tissue almost as much as the malignancy itself, the idea that a bacterial product might freeze tumor growth without collateral damage is as provocative as it is counterintuitive.

From waterborne killer to lab tool

The starting point for this work is the long studied pathogen Vibrio cholerae, whose toxins drive the severe diarrhea that defines cholera outbreaks. In Umeå, scientists isolated MakA, described as a purified cytotoxin secreted by this bacterium, and began testing its effects on colorectal cancer cells grown in controlled conditions. According to detailed reports on these experiments, the Ume team saw a clear cancer inhibiting effect that justified moving quickly into animal models. What began as a basic microbiology project has therefore evolved into a serious oncology program, with MakA now treated less as a curiosity and more as a candidate therapeutic scaffold.

In parallel, other investigators have mapped how a broader cholera derived toxin reshapes the tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer. These Researchers at Umeå University have documented how exposure to the toxin suppresses colorectal tumor growth while avoiding the significant side effects that often accompany conventional chemotherapy. By focusing on the precise molecular components of Vibrio cholerae, including MakA, the Umeå group has turned a classic infectious disease threat into a finely tuned probe of cancer biology, and potentially into a future drug platform.

MakA’s double hit on tumors and immunity

What makes MakA stand out is not just that it slows colorectal cancer growth, but that it appears to do so through a two step mechanism. On one level, MakA behaves like a classic cytotoxin, directly damaging cancer cells and limiting their ability to divide. On another level, detailed analyses of treated tumors show that the toxin also stimulates immune activity inside the malignancy, effectively turning a “cold” tumor into a “hotter” one that is easier for the body to recognize. Reports on toxin secreted by describe both tumor shrinkage and an enhanced immune response in colorectal cancer models, a combination that is particularly attractive in the era of immunotherapy.

In animal studies, the Umeå research team has shown that MakA can slow the growth of colorectal tumors without causing measurable damage to the rest of the body. One summary of their work notes that the toxin’s effect appears local and specifically targeted at tumors, with further analyses confirming that MakA stimulates immune cells in the tumor microenvironment rather than only killing cancer cells directly. That local, dual action profile is highlighted in coverage of how Further experiments linked MakA exposure to increased immune cell infiltration, suggesting that the toxin may act as both a direct anticancer agent and an in situ vaccine that flags tumor cells for destruction.

Healthy tissue spared in early models

For any toxin based therapy, the central question is whether the same destructive power that harms cancer cells will also injure healthy organs. In the MakA studies, that concern has been front and center, and the early data are striking. Researchers report that a toxin secreted by cholera bacteria can inhibit the growth of colorectal cancer without causing any measurable damage to the body, a claim backed by careful monitoring of treated animals for systemic toxicity. One detailed account notes that bacterial toxin treatment did not produce the weight loss, organ damage, or blood abnormalities that typically accompany high dose chemotherapy.

That safety signal is echoed in descriptions of how MakA’s effect is confined to the tumor site. The Umeå team emphasizes that the purified substance was studied specifically to limit damage to surrounding tissue, and early results suggest that this design goal is being met. Reports on how the researchers in Umeå approached dosing and delivery describe a careful balance between achieving tumor control and preserving normal physiology. In an oncology landscape where patients often trade quality of life for marginal survival gains, the prospect of a therapy that spares healthy tissue while freezing tumor growth is a powerful draw.

Inside the tumor: reshaping immunity from within

Beyond direct toxicity, the most intriguing aspect of the cholera derived approach is how it appears to reprogram the immune landscape inside colorectal tumors. Detailed immunology work from Umeå University shows that exposure to the toxin changes the balance of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, tipping it away from suppression and toward active attack. Coverage of this work notes that Ume scientists documented a reshaped tumor immunity profile that correlated with slower colorectal cancer growth, all without the significant side effects that often accompany systemic immune stimulants.

MakA appears to be central to this immune remodeling. In analyses of treated tumors, investigators found signs that the cytotoxin was not only damaging cancer cells but also releasing tumor antigens in a way that made them more visible to T cells and other immune effectors. Reports on how the Umeå research team examined MakA, described as a cytotoxin secreted by the cholera bacterium Vibrio cholerae, emphasize that this dual role could make it a valuable tool for future combination therapies. One summary of this work notes that Studying this cholera derived cytotoxin has already provided new tools for understanding how to turn immunologically silent colorectal tumors into responsive ones.

From lab bench to potential therapy

As promising as the MakA data look, they remain preclinical, and the path from mouse models to human treatment is rarely straightforward. The Umeå group is clear that MakA is a starting point rather than a finished drug, and that extensive engineering will be needed to fine tune its potency, stability, and delivery. Still, the fact that a cholera derived toxin can stop colon cancer growth without harming healthy tissue in early models has energized efforts to translate the work. Reports on how the toxin stops colorectal tumor growth describe a clear next step: designing delivery systems that keep MakA’s action tightly localized while allowing for repeat dosing.

For clinicians and patients, the most immediate impact of this research may be conceptual rather than practical. It reinforces the idea that some of the most effective cancer tools may come from unexpected corners of biology, including pathogens that have plagued humanity for centuries. Detailed coverage of how a bacterial toxin only kills cancer cells directly, while sparing healthy tissue, underscores how far the field has come from blunt chemotherapies toward targeted, mechanism based interventions. As researchers continue to refine MakA and related molecules, the notion that a deadly toxin could one day be part of a standard colorectal cancer regimen no longer feels like science fiction.

More from Morning Overview