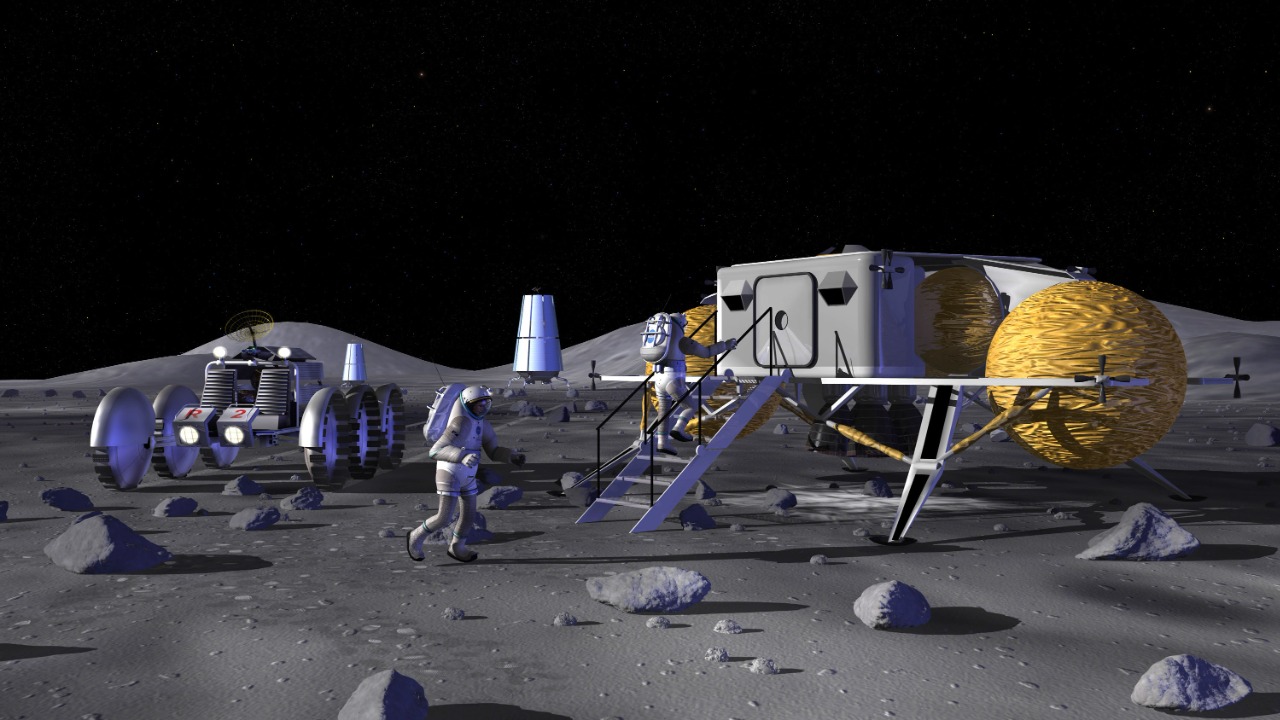

Nuclear power on the Moon has moved from science fiction to a concrete target on the United States space agenda. NASA and the Department of Energy now have a shared goal of operating a fission reactor on the lunar surface by 2030, treating reliable electricity as the backbone of any long term human presence. The question is no longer whether the idea is serious, but whether the technology, politics and timelines can line up in time.

If it works, a compact reactor could give astronauts continuous power through the two week lunar night, support heavy industry in low gravity and even help test systems for future missions to Mars. If it slips, the United States risks ceding both technological and strategic ground to rivals that are also eyeing nuclear systems in space. I see the current push as a test case for how quickly the country can turn ambitious space policy into hardware on another world.

NASA’s 2030 deadline and why it matters

NASA has publicly committed to putting a working nuclear reactor on the Moon by the end of this decade, framing the project as essential to its broader Artemis exploration plans. Agency leaders have described a fission surface power system that can operate independently of sunlight, providing tens of kilowatts of electricity for at least a decade without refueling, and they have tied that capability directly to permanent bases near the lunar south pole. In partnership with the US Department of Energy, NASA has set 2030 as the target year for having such a system operating on the surface, a goal that has been reiterated in multiple policy and technical briefings.

The scale of that commitment is clear in the way NASA and the DOE have formalized their cooperation. A joint agreement described how NASA, DOE aim to deliver a lunar fission system by 2030, and a separate explainer underscored that NASA plans to put a nuclear reactor on the Moon on roughly that same schedule. In Jan, additional reporting stressed that NASA is serious about having a fission power plant on the lunar surface by that year, treating the deadline as a central organizing principle rather than a vague aspiration.

Inside the NASA–DOE pact to build a lunar reactor

To turn that deadline into hardware, NASA has leaned heavily on the Department of Energy’s nuclear expertise, formalizing a collaboration that goes beyond a typical interagency memo. In Jan, the agency announced that “Achieving this future requires harnessing nuclear power,” and that a new agreement with the Departm of Energy would enable closer work on both fission surface power and related technologies. The statement framed nuclear energy as a bridge between civil space exploration and terrestrial power innovation, with NASA explicitly calling out the need to integrate reactor design, fuel development and launch safety into a single program.

Follow up reporting described how Achieving this future would rely on the Departm of Energy’s long experience with reactors and fuel cycles, while NASA brings launch, landing and surface operations to the table. Another Jan analysis noted that NASA’s and the ambitions for a lunar fission surface power (FSP) system have faced delays and uncertainty, but that the new pact is meant to lock in responsibilities and funding. A separate briefing on research and development emphasized that in Jan the DOE And Nasa 2030, describing an Agreement that includes a system designed to run for years without the need to refuel.

Why nuclear beats solar on the Moon

The case for nuclear power on the Moon starts with a simple constraint: sunlight is unreliable and intermittent on much of the surface. Near the equator, the lunar night lasts roughly fourteen Earth days, which would force solar powered bases to rely on enormous battery banks or fuel cells to survive. Even at the south pole, where some ridges see near constant light, dust, shadowed craters and terrain make it difficult to guarantee steady solar input for habitats, mining equipment and communications gear. A compact fission reactor, by contrast, can deliver continuous output regardless of local lighting, temperature swings or dust storms.

NASA officials have been explicit that they see nuclear systems as the only realistic way to support industrial scale activity and human life through the long lunar night. One Jan briefing stressed that Establishing a power source on the Moon that can provide continuous, always on electricity is a key enabling technology, with plans for units that deliver around 40 kW each of electricity for extended periods, a point highlighted in Establishing a power. Another technical overview explained that NASA wants a plant that can operate for years without constant fuel resupply from Earth, describing a fission system that avoids the logistics burden of shipping propellant or batteries every mission, as outlined in a report that noted constant fuel resupply would be unsustainable for long term bases.

Strategic stakes: from Artemis to geopolitics

Beyond engineering, the lunar reactor push is wrapped up in national strategy and competition. NASA has tied the project directly to Artemis, arguing that a robust power plant is necessary to support astronauts on the surface and to test technologies that could later be used on Mars. Officials have also acknowledged that other countries, including Russia, are pursuing their own nuclear space capabilities, raising concerns that the first nation to master reliable off world reactors could gain both scientific and military advantages. In that context, a functioning fission plant on the Moon becomes a symbol of technological leadership as much as a practical asset.

One detailed account of NASA’s planning explained that the agency wants to build a nuclear power plant on the Moon in the next decade to support Artemis astronauts and future missions to Mars, while also noting that similar ambitions in Russia are raising national security concerns, a point captured in a report that stated NASA plans to build a plant while watching Russia. Another Jan policy watch noted that NASA and DOE are planning a nuclear reactor on the Moon in roughly four years, and that the same agreement also covers nuclear propulsion technologies for space exploration, linking surface power to future deep space missions. A separate analysis argued that Sustainable nuclear power, and an internet connection from the Moon to Earth, are vital precursor components to a permanent lunar presence, describing how Sustainable energy and communications will shape who sets the rules in cislunar space.

How realistic is “soon” for a lunar reactor?

Whether NASA can actually switch on a reactor on the Moon by 2030 depends on how it navigates technical risk, funding cycles and public perception. The agency’s own history with nuclear systems in space is mixed, with successful radioisotope generators on missions like Voyager and Curiosity but no prior attempt to land and operate a full fission plant on another world. Engineers must design a system that can survive launch, landing shocks, lunar dust and extreme temperature swings, all while meeting strict safety standards for handling enriched fuel. Political support will also have to hold through multiple administrations, since the project spans most of a decade.

More from Morning Overview