China is betting that a radical new way to move heat, using salt and pressure instead of traditional refrigerants, can cool the hottest data centers in a matter of seconds. The approach relies on a liquid that plunges from room temperature to far below 0°F almost instantly, soaking up heat from nearby electronics as it changes state. If it scales, this kind of supercooling could reshape how I think about building and powering the infrastructure behind artificial intelligence.

At a time when AI clusters are straining power grids and pushing conventional chillers to their limits, Chinese researchers are pitching this technology as both a performance upgrade and a strategic asset. By turning a basic chemical interaction into a controllable cooling cycle, they are trying to carve out an edge in the global race to run larger, denser compute farms without melting the hardware.

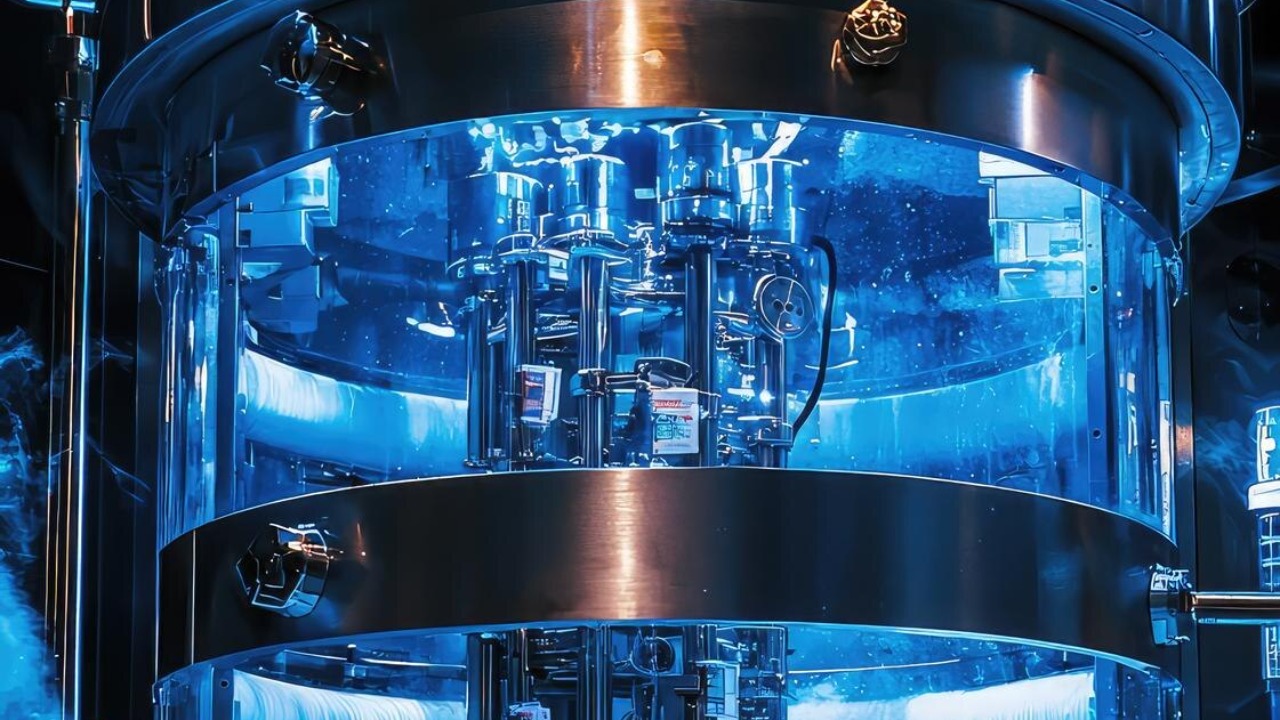

How ‘salt and pressure’ turns chemistry into instant cold

The core idea is deceptively simple: use pressure to keep a special liquid stable at room temperature, then release that pressure so the liquid rapidly cools and absorbs heat from its surroundings. Chinese teams describe a formulation that can drop from ambient conditions to well below 0°F in seconds, creating frost on contact surfaces almost immediately. In effect, the fluid becomes a tunable heat sponge, pulling energy out of chips and server racks as it races through this sudden temperature plunge.

What makes this different from a standard refrigerant loop is the role of dissolved salts and the way they respond to mechanical stress. In the reported experiments, Chinese researchers use pressure to hold the solution in a metastable state, then trigger a rapid phase change that drags the temperature down while drawing in heat from nearby components. Because the process is driven by a reversible chemical transition rather than continuous compression of a gas, it promises faster response times and potentially lower energy overhead for each cooling cycle.

From frost in 20 seconds to AI-ready data halls

In early demonstrations, the most striking visual is speed: test rigs reportedly show frost forming on metal surfaces in about 20 seconds once the system is activated. That kind of response is not just a party trick. For dense AI servers that can spike from idle to full load in milliseconds, a cooling system that can swing quickly from standby to deep cold is a serious advantage. It means the infrastructure can chase the workload, rather than running flat out all day just in case the GPUs surge.

Reports on the prototype liquid cooling system describe it as a candidate for critical infrastructure, from hyperscale data centers to national AI platforms. The pitch is that by pairing this ultra-fast thermal response with direct-to-chip or immersion setups, operators could offset soaring energy consumption and cooling demand as they scale up large language models and other compute-heavy workloads. In that framing, frost in 20 seconds is less about spectacle and more about keeping multi-billion-parameter models online without overbuilding chillers and backup power.

Why China sees a strategic edge in sub-zero seconds

China’s interest in this technology is not happening in a vacuum. As AI training clusters grow, cooling has become a bottleneck that shapes where facilities are built and how much capacity they can realistically support. By pushing a homegrown solution that can hit sub-zero temperatures in seconds, China is trying to reduce dependence on imported cooling hardware and refrigerants while claiming a performance edge for its own AI infrastructure. The fact that the approach is framed explicitly around data centers signals that this is as much about industrial policy as it is about thermodynamics.

One detailed account of China’s ‘salt and stresses that the method is designed to absorb heat from racks of servers in a very short window, then reset for another cycle. That kind of rapid, repeatable operation is exactly what hyperscale operators need as they stack more accelerators into each rack. If the system can be engineered into modular units, it could give Chinese cloud providers a way to pack more compute into existing buildings without breaching thermal limits, a clear competitive advantage in the AI race.

The physics behind the magic: salts, crystals and nanostructures

Under the hood, the trick relies on how salts behave when they dissolve, crystallize and respond to pressure. When a salt dissolves in water, it can either release heat or absorb it, depending on the chemistry. By choosing salts and concentrations that favor strong endothermic transitions, and then using mechanical pressure to hold the mixture in a high-energy state, engineers can store a kind of “cooling potential” that is unleashed on demand. The result is a liquid that looks ordinary at rest but can, when triggered, yank heat out of its environment at remarkable speed.

Some of the most vivid illustrations of this behavior come from microscopy work that shows how salt crystals form and strain as water evaporates. In one such study, researchers track how perfectly spherical droplets dry and how the salt crystallises quickly from the outside, each crystal straining against its neighbors as the structure grows. That process, captured in As the droplets shrink, highlights the intense mechanical and thermal forces at play when salts move between dissolved and solid states. The new cooling systems essentially harness those same transitions, but in a controlled loop that can be cycled inside a data center rather than on a microscope slide.

From lab breakthrough to industrial-scale coolant

For now, the salt and pressure approach is still closer to a lab breakthrough than a standard feature in commercial server rooms, but the ambitions are clear. Chinese teams describe a liquid that can drop from room temperature to extreme cold in a tightly managed cycle, and they explicitly link that capability to the explosive growth in AI computing. In one account, Chinese researchers frame the technology as a way to keep up with that growth without letting energy use spiral out of control, since more efficient cooling can cut the overhead power needed to run each data hall.

The path from prototype to industrial deployment will hinge on reliability, cost and integration with existing infrastructure. Operators will want to know how many cycles the fluid can endure before its performance degrades, how the pressure vessels and pumps behave under continuous load, and whether the salts pose any corrosion or contamination risks to sensitive electronics. Yet the direction of travel is unmistakable. Earlier descriptions of the breakthrough, including a widely shared Feb announcement, present it not as a curiosity but as a candidate backbone for the next generation of AI-ready data centers. If those promises hold up under real-world conditions, the idea of chilling racks to sub-zero in seconds may soon move from viral video to standard operating procedure.

More from Morning Overview