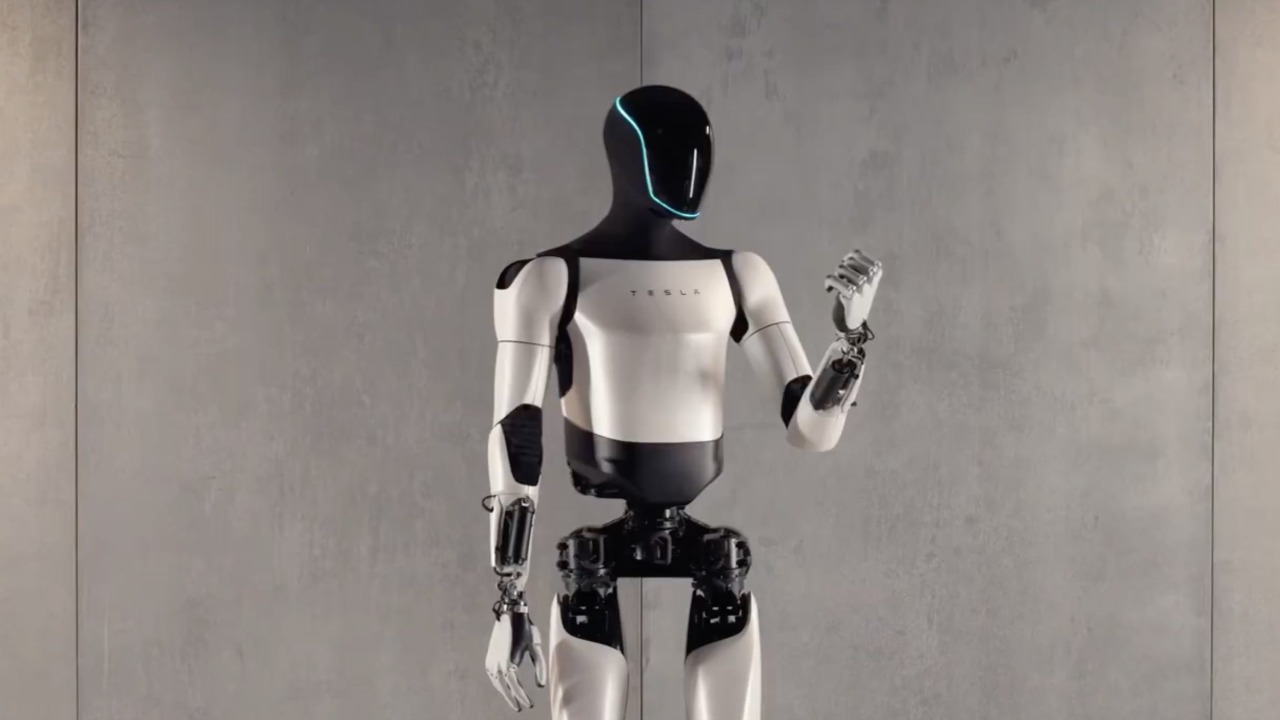

Elon Musk wants Optimus humanoid robots to be the next mass-market machine to roll out of Tesla’s factories, a kind of Model 3 for physical labor. Yet the closer Optimus gets to commercial reality, the clearer it becomes that the project is tethered to a supply chain that runs through China, not through the American industrial heartland Musk likes to invoke. The dream of a domestically built robot workforce is colliding with the hard math of components, export rules, and geopolitical leverage.

Instead of a clean break from global dependencies, Optimus is emerging as a case study in how deeply China’s manufacturing ecosystem is embedded in advanced hardware. I see a tension between Musk’s ambition to scale robots in places like Fremont, California, and the reality that key parts, from motors to sensors, are controlled by Chinese suppliers who now understand just how much power that gives them.

Optimus meets the ‘Optimus chain’

At the core of the story is a simple fact: Optimus is being built on top of a dense network of Chinese partners that analysts have started calling an “Optimus chain.” According to reporting that cites the South China Morning Post, Tesla has set up cooperative relationships with hundreds of Chinese companies to secure everything from actuators to precision gearboxes, driving down component prices to a level that makes a humanoid robot even vaguely affordable. Those suppliers form the backbone of the project, providing the “bodies” of the machines while Tesla focuses on software and integration.

Industry analysis frames this division of labor bluntly as “Chinese Suppliers Critical for Cost Efficiency as U.S. Leads in AI, China Dominates Hardware,” with the phrase “Chinese Suppliers Critical for Cost Efficiency” and “China Dominates Hardware” used to describe how the global split between algorithms and manufacturing plays out in practice. One report, credited “By Park Ji-min” and marked “Published 2026.02.02,” underscores that this 02.02 snapshot of the market shows hardware capacity clustered in China and software leadership in the United States, a gap that Optimus cannot bridge without leaning heavily on that existing base. In other words, the robot’s brain may be American, but its skeleton is firmly rooted in Chinese industrial parks.

Cost targets that lock in dependence

Musk has set an aggressive price goal for Optimus, telling investors that Tesla is aiming to push the cost of each unit down to $20,000. For Tesla, which aims to reduce Optimus’s cost to $20,000, exiting the Chinese supply chain is not feasible. Analysis suggests that trying to replicate the same hardware ecosystem in another country would add layers of cost and delay that would blow up that price point and erode the business case for humanoid robots in warehouses and factories.

Other assessments go further, warning that excluding Chinese parts could almost triple the cost of the robot. One breakdown of the bill of materials argues that “Excluding Chinese” suppliers from Optimus would force Tesla to source motors, sensors, and structural components from higher cost regions, undermining the entire premise of a relatively cheap general-purpose robot. That is why multiple reports describe Tesla Optimus Robot Production Reliant on Chinese Suppliers Despite US Assembly Plans, with “Tesla Optimus Robot Production Reliant” and “Chinese Suppliers Despite US Assembly Plans” used to stress that even if final assembly happens in the United States, the value chain still runs through Asia.

Export curbs and rare earth leverage

The dependence is not just about price, it is also about control. Earlier, Apr reporting from Reuters quoted Tesla, TSLA, CEO Elon Musk acknowledging that production of Optimus humanoid robots had been affected by China’s export curbs on rare materials. He said China wants assurances that the robots will not be used for military applications before it signs off on key shipments, a reminder that the same country supplying critical parts can also slow or stop them for strategic reasons. A companion Apr dispatch from Reuters, again citing Tesla, TSLA, CEO Elon Musk, noted that he still hoped to build thousands of Optimus robots this year but could offer “no guarantees” while export rules were in flux.

Those curbs are part of a broader pattern. A separate analysis framed the situation as Tesla Optimus Robot Hit By China Rare Earths Crackdown, with the phrase “Tesla Optimus Robot Hit By China” and “Rare Earths Crackdown” used to describe how new licensing rules on specialized metals ripple through the supply chain. In that same context, Elon Musk Says Thousands May Be Ready By Year, End, But No Guarantees, a formulation that captures both his optimism and his lack of control over upstream constraints. When the Chinese government classifies certain robot technologies as sensitive and folds them into export review, as one report on “Additionally, the Chinese government classifies” notes, it effectively inserts a political checkpoint into every Optimus production plan.

Officials, licensing, and the security squeeze

Regulatory friction has already surfaced in concrete ways. One detailed account described how Officials seek assurances that bot will not be used for military applications, with Officials pressing Tesla on the end uses of Optimus before approving export licenses for certain components. The same report, written by Richard Speed and timestamped Wed 23 Apr 2025 // 16:32 UTC, highlighted how even a single restricted chip or actuator can become a chokepoint if it is classified as a dual use item. That “32” in the timestamp is a small detail, but it underscores how granular and bureaucratic the process can be.

From my perspective, this is where Musk’s rhetoric about an “all-American” robot runs into the reality of Chinese Supply Chain politics. According to one account that cites the South China Morning Post, Chinese Supply Chain experts have warned Tesla that trying to ditch the all-American Optimus dream and cut Chinese partners out of the loop would be self defeating. The same piece notes that According to the South China Morning Post, SCMP, Tesla is being reminded that its component supply chain is cost efficient precisely because it is anchored in China, and that any attempt to reconfigure it quickly would face both economic and regulatory headwinds.

China’s own humanoid push raises the stakes

While Tesla wrestles with these constraints, Chinese companies are not standing still. In Feb, robotics firm Unitree has been showcasing its G1 humanoid robot, which can walk on two legs, recover balance after impact, and perform complex motions like kickboxing, according to one detailed profile. The same report notes that Until now, the humanoid race has been framed as a contest between American AI and Chinese hardware, but Unitree’s progress suggests that Chinese players are moving up the value chain into software and autonomy as well. That raises the prospect that Optimus will not just be assembled from Chinese parts, it will also face direct competition from Chinese brands in global markets.

Another Feb analysis of China’s Ultra-Cheap Humanoid Robots Take On America’s AI framed the landscape as likely to split along familiar lines, with low cost Chinese machines undercutting Western rivals on price. In that context, “Cost and efficiency remain the Chinese supply chain’s key advantages,” as analyst Zhang Xin at brokerage Longbridge Dolphin put it, a quote that appears in a report on how Cost and efficiency remain the Chinese supply chain’s key advantages. When Zhang Xin and Longbridge Dolphin talk about a clear mass production timetable for Chinese humanoids, they are effectively describing the same industrial muscle that Tesla is tapping for Optimus, only now it is being used to build competitors too.

More from Morning Overview