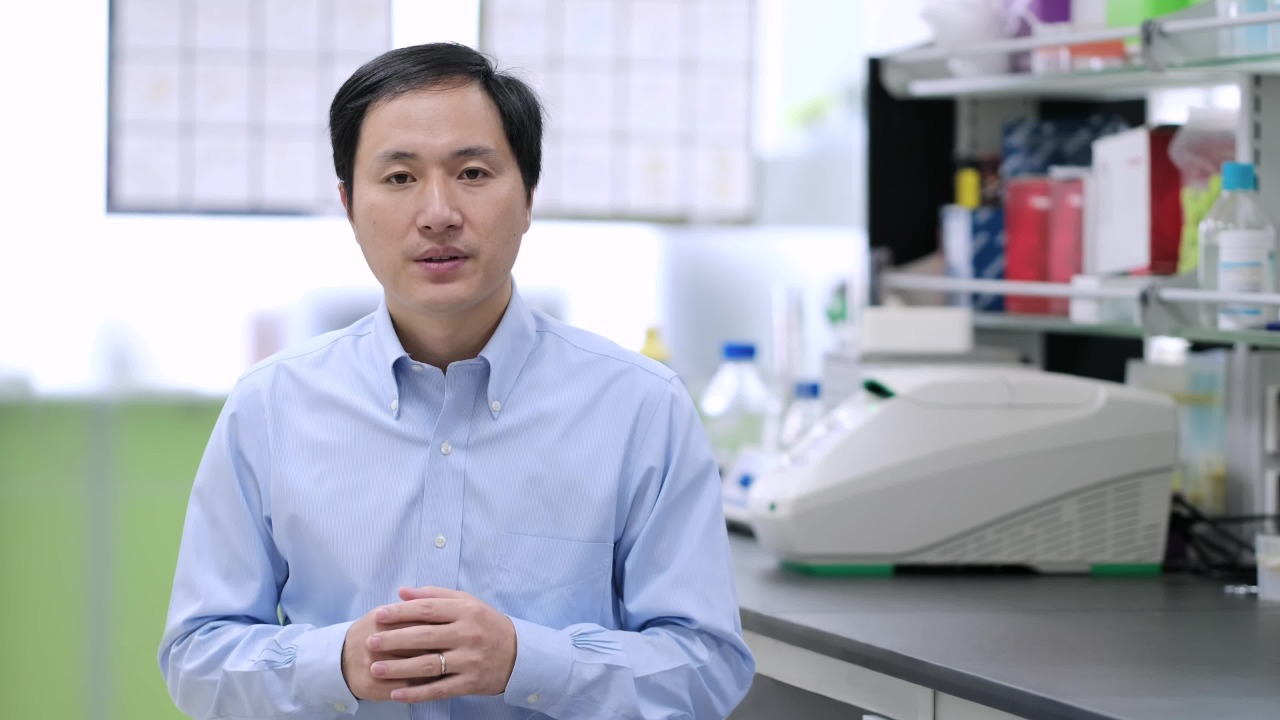

He Jiankui, the biophysicist who created the world’s first gene-edited babies and was branded China’s “Frankenstein,” has completed his prison term and is quietly rebuilding a scientific career. His release and return to the lab have reopened a fierce argument over how far society should go in forgiving a researcher whose work permanently altered the human germline.

As he steps back into public life, He is testing how much trust, funding and freedom a disgraced scientist can regain in a field where a single experiment can reshape generations. The answer will help define not only his future, but also the global rules of engagement for human genome editing.

The experiment that shocked the world

Long before the prison cell, He Jiankui was a rising star of Scientific genetics in China, trained abroad and recruited back as part of a national push into cutting edge biotechnology. He focused on CRISPR, the gene-editing tool that allows precise changes to DNA, and set his sights on modifying embryos to resist HIV infection. The project culminated in the birth of three babies whose CCR5 genes were altered, a step he initially framed as a bold public health intervention.

What he presented as a medical breakthrough was, in reality, a secretive clinical experiment that bypassed established safeguards. An investigation later found that His team raised money and operated outside normal university and government oversight, recruiting couples into a trial that had not passed rigorous ethical review. The Editing Scientist altered the genes of three babies, and critics warned that the changes could introduce new mutations or health risks that would be passed on to their descendants.

From celebrity scientist to criminal defendant

Once the births became public, Chinese authorities moved quickly to distance the state from the work and to reassert control. The People’s Court of Nanshan concluded that He and two collaborators had acted in the pursuit of “fame and profit,” violating regulations on medical research. He Jiankui was convicted of illegal medical practice and handed a three year sentence and a substantial fine, while his colleagues received lesser penalties.

State media underscored that a scientist in China who claimed to have created the world’s first gene-edited babies had broken both the law and basic research ethics. Reports stressed that He Jiankui had forged documents and misled hospital staff, and that the trial was meant to signal a clear boundary around human embryo editing. Internationally, coverage highlighted that He Jiankui, a Chinese researcher once showcased at a conference in Hong Kong, had become a cautionary tale for the entire field.

Release, remarriage and a carefully staged comeback

After serving his term, He Jiankui was released from prison in early 2022 and began the slow work of reentering public life. A Daily briefing described the CRISPR baby creator as out of jail but still facing informal professional sanctions, while His research activities remained suspended. The same period saw him take a short appointment at Wuchang University of Technology, a role that ended after a few months as public scrutiny intensified.

His personal life also became part of the story. According to a leaked WeChat post cited in one profile, his ex-wife divorced him in 2024 “because of a major fault on his side.” Since his release, he has cultivated a new public image that mixes family snapshots, golf games and glimpses of lab work, a curated feed that softens the edges of the man once portrayed as a rogue.

Back in the lab, with patients at the door

Despite the stigma, He Jiankui is again running experiments. Reports describe him as a He Jiankui who spent three years in prison and now sees a greater opening for research as China and other countries race to commercialize gene therapies. In interviews, he has said he wants to focus on rare diseases, telling one newspaper that he hopes to use genome editing in human embryos to develop treatments for conditions such as inherited muscle disorders, even as he acknowledges the legal and ethical constraints that still surround embryo work.

The demand for help is real. In one account, he described how, after his release, Then something unexpected happened: There were over 2,000 DMD patients who wrote, texted and called him, pleading for experimental treatments that mainstream medicine could not yet offer.

“China’s Frankenstein” and the ethics of a second chance

His reemergence has revived a debate that stretches far beyond one man. Commentators in Responding to the Comeback of He have framed him as CRISPR Baby Scientist whose case offers Lessons for Criminal Justice Theory: how should societies reintegrate offenders whose work, while unlawful, also sits at the frontier of innovation. Some ethicists argue that a completed sentence should open the door to supervised research, while others insist that the unique harm of germline editing justifies a permanent professional ban.

Public opinion is equally divided. A viral video on human genome editing asked whether man can play God, placing He’s experiment at the center of a broader anxiety about designer babies and genetic inequality. At the same time, online discussions note that a Chinese scientist who was imprisoned for his role in creating the first genetically edited babies now says he has returned to the lab and wants to respect ethical boundaries, a message shared widely in Futurology forums.

More from Morning Overview