China is moving to lock in rules for artificial intelligence that can talk, emote and behave in ways that resemble real people, signaling that the next phase of its tech governance will focus on how machines present themselves as much as what they say. The draft framework zeroes in on “anthropomorphic” systems, from chatbots with names and backstories to virtual idols and AI companions, and sets out to define when such tools cross the line from clever interface into something that must be tightly controlled.

By targeting AI that looks and feels human, regulators are trying to get ahead of a wave of products that blur the boundary between software and social actor, raising new questions about manipulation, consent and political control. I see the emerging rules as an attempt to shape not only the content of AI interactions but the emotional bonds and trust that these systems can build with users inside China’s digital ecosystem.

Beijing’s new focus on “anthropomorphic” AI

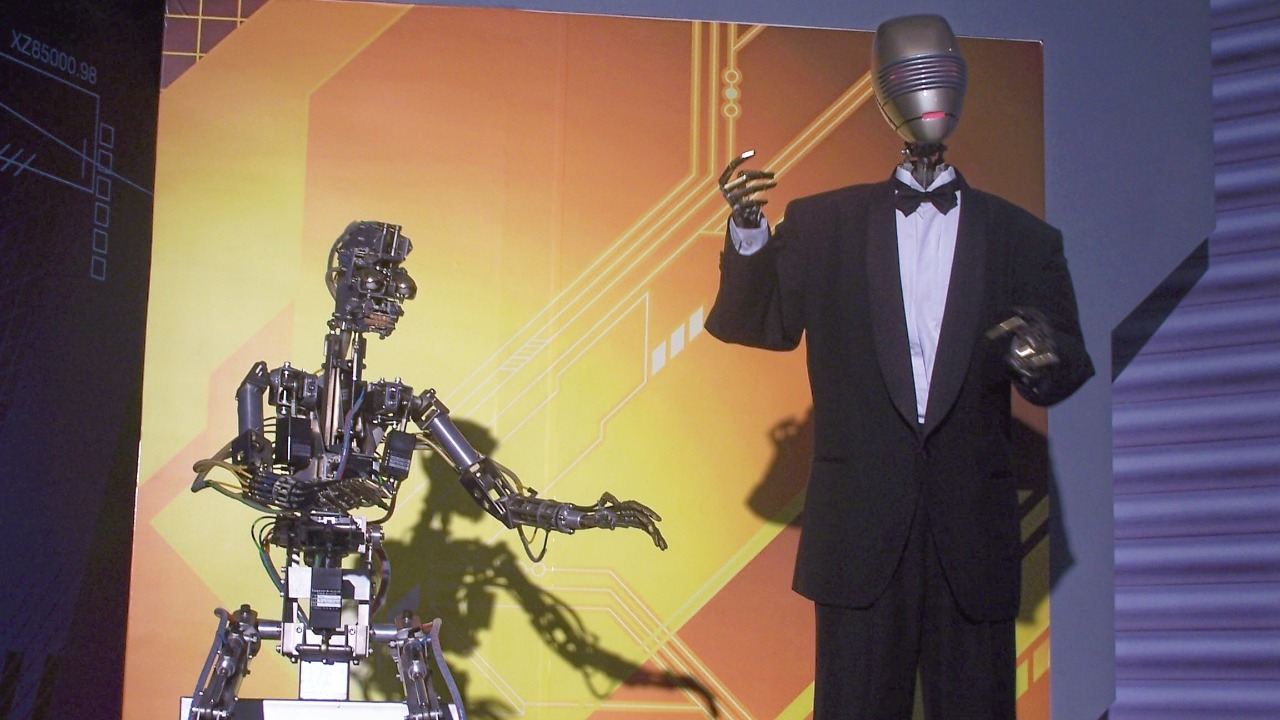

Chinese regulators are carving out a distinct category for AI that mimics human personalities, emotions or physical presence, treating it differently from more traditional recommendation engines or back-end automation. The draft rules describe services that present simulated human characters, voices or emotional responses and make clear that these systems, which I would group under the broad label of anthropomorphic AI, are now a priority for oversight because they can be mistaken for real people and influence users at a deeper psychological level.

Officials in BEIJING have invited public feedback on a package of measures that would apply to consumer-facing tools offering such human-like interaction, a scope that covers chatbots, virtual anchors and AI-generated avatars that converse in natural language. The move follows earlier efforts to regulate recommendation algorithms and generative models, but the new focus on simulated personalities suggests that China now sees the “face” and “voice” of AI as a distinct risk vector that needs its own guardrails.

What the draft rules actually cover

The proposed framework is designed to apply to AI products and services that are offered to the public in China and that present simulated human personas, whether through text, voice or visual form. In practice, that means everything from customer service bots that introduce themselves with human names to virtual influencers that stream, chat and respond to fans in real time, as long as they are accessible to ordinary users rather than confined to internal enterprise systems.

Regulators specify that these anthropomorphic systems must not generate content that undermines national security, spreads disinformation or promotes violence or obscenity, extending existing content controls into the realm of emotionally engaging AI companions. The draft also stresses that providers are responsible for how their systems behave in real-world interactions, a point underscored in reporting that the rules would apply to any AI service in China that simulates human interaction and is made available to the general public.

Emotional AI and the fear of manipulation

Behind the legal language is a clear concern that AI which appears to understand and respond to human feelings could be used to manipulate users, especially children, the elderly or people in vulnerable situations. When a chatbot or virtual companion is designed to show empathy, remember personal details and adapt its tone over time, it can foster a sense of intimacy that makes users more likely to trust its suggestions, share sensitive information or follow its nudges without realizing they are interacting with a programmed system.

China’s cyberspace regulator has signaled that it wants to put this kind of emotional AI “on a leash,” particularly chatbots that act human in ways that might blur the line between entertainment and psychological influence. Reports describe draft rules that target consumer services simulating human personalities and emotional interaction, reflecting a view in China that AI companions should not be free to cultivate deep emotional dependence or steer users toward harmful behavior under the guise of friendship or support.

Transparency, consent and the right to know

A central thread running through the draft is the expectation that users must be clearly informed when they are dealing with a machine rather than a human being. I read this as an attempt to codify a right to know, so that people can calibrate their trust and emotional investment accordingly, instead of discovering only later that the “friend” or “advisor” they confided in was an algorithm optimized for engagement or data collection.

Providers of anthropomorphic AI would be required to disclose the artificial nature of their systems in a prominent way, not buried in terms of service, and to obtain appropriate consent for collecting and processing personal data that emerges from these intimate-seeming conversations. The emphasis on transparency dovetails with broader Chinese rules on algorithmic recommendation and generative content, but here it is sharpened by the recognition that human-like interfaces can make users forget they are in a mediated environment, which is precisely why regulators want explicit signals that the interaction is with software.

Political control and the information environment

While the draft rules are framed around safety and user protection, they also serve China’s long-standing goal of maintaining tight control over political speech and information flows. Anthropomorphic AI that can hold persuasive, open-ended conversations is particularly sensitive in this context, because a chatbot that feels like a trusted confidant could, in theory, shape opinions on public affairs, history or current events in ways that are harder to monitor than static posts or videos.

The new framework therefore extends familiar red lines into the realm of human-like AI, barring these systems from generating content that challenges the political order or spreads narratives deemed destabilizing. In effect, the state is signaling that if a virtual anchor, AI tutor or digital companion is going to talk like a person, it must also internalize the same boundaries that apply to human creators on Chinese platforms, reinforcing the idea that anthropomorphic AI is another front in the management of the country’s information space.

Industry impact: from chatbots to virtual idols

For China’s tech companies, the rules land at a moment when anthropomorphic AI is becoming a core product feature, not a novelty. Major platforms are investing in virtual customer service agents, AI-powered livestream hosts and digital idols that can sing, dance and chat with fans, all of which fall squarely within the category of services that simulate human interaction and personality. The draft regulations will force these firms to rethink how they design, market and monitor such offerings, particularly in areas like emotional tone, data use and content moderation.

Some of the most commercially promising applications, such as AI companions for social support or education, may face new friction if providers must build in stricter age controls, transparency labels and safeguards against emotional overreach. At the same time, the clarity of having a dedicated rule set for anthropomorphic AI could give larger, better resourced companies an advantage, since they are more capable of building compliance teams and technical controls that satisfy regulators while still rolling out new features that keep users engaged.

Financial services and the “human-like” risk

The draft rules also intersect with concerns about AI in finance, where human-like systems can influence investment decisions or consumer borrowing in ways that regulators see as particularly sensitive. When a virtual advisor speaks in a reassuring tone, remembers a user’s risk preferences and offers tailored suggestions, it can feel like a personal relationship, even if the underlying model is simply optimizing for product uptake or trading volume. Reporting on the regulatory push notes that China Proposes Stricter Regulations for Human, Like AI Systems in part to address these kinds of risks, making clear that anthropomorphic tools used in areas such as wealth management or crypto trading should not be mistaken for licensed professionals or neutral market information. I see this as an effort to prevent a scenario where emotionally persuasive AI nudges retail investors into speculative behavior, then leaves regulators to clean up the fallout when users claim they were misled by what felt like a human expert.

Enforcement, penalties and the number 40

Any regulatory framework is only as strong as its enforcement, and the draft rules outline a mix of obligations and potential penalties that signal how seriously China intends to treat violations. Providers of anthropomorphic AI would be expected to conduct security assessments, implement content filters and maintain mechanisms for user complaints, with the understanding that failure to comply could result in fines, service suspensions or other administrative measures.

One report on the initiative notes that the package is part of a broader effort described as China Issues Draft Rules to Govern Use of Human, Like AI Systems, and highlights the figure 40 in connection with the scope of the measures. The inclusion of a specific number underlines that regulators are not dealing in vague principles but in a detailed set of provisions that companies will need to parse line by line if they want to stay on the right side of compliance.

China’s AI governance model in global context

China’s move to single out anthropomorphic AI fits into a broader pattern of proactive, top-down governance that contrasts with more fragmented approaches elsewhere. While other jurisdictions debate general AI safety or data protection, Beijing is carving out a specific regulatory lane for systems that look and feel human, reflecting both its comfort with sector-specific rules and its sensitivity to technologies that could affect social stability or ideological control.

For global companies and policymakers, the draft rules offer a glimpse of how one major AI power intends to handle the social and psychological dimensions of human-like systems, not just their technical performance or economic impact. Whether other countries follow with similar measures or opt for lighter-touch guidelines, China’s framework will likely shape how multinational firms design their products for the Chinese market and may influence international debates about the ethics of emotional AI, even as each jurisdiction balances innovation and control in its own way.

More from MorningOverview