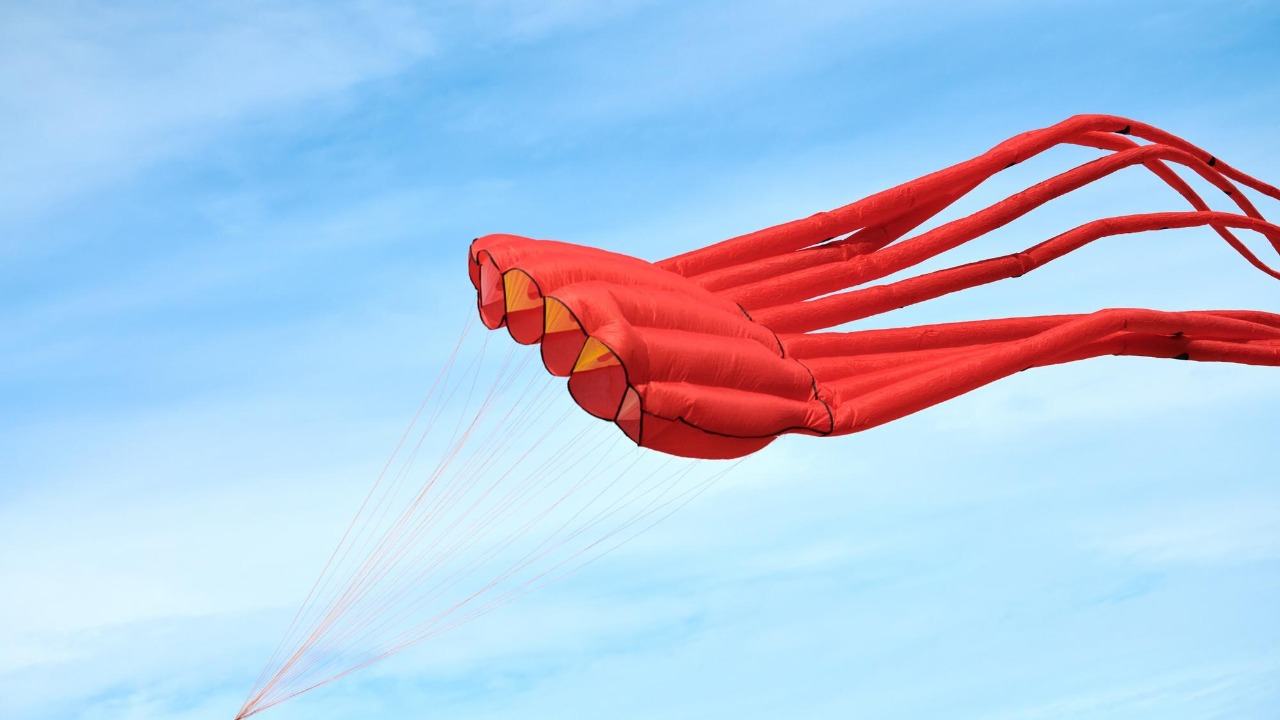

China has quietly turned a childhood toy into a piece of heavy infrastructure, unveiling a giant power-generating kite that behaves more like an airborne power station than a beach plaything. The experimental system, which spans an enormous 5,000 square metres of fabric, is designed to tap the stronger, steadier winds high above the ground and turn them into grid-ready electricity. If it scales as planned, it could give the country a new way to feed its vast energy appetite while cutting emissions.

Engineers behind the project describe a machine that does not just float in the sky but actively flies complex patterns to squeeze as much energy as possible from the upper atmosphere. The result is a super‑kite that can climb, dive and bank under algorithmic control, pulling on its tether with enough force to spin generators on the ground. It is a striking example of how China is trying to leapfrog conventional hardware in the race to dominate the next wave of clean power technology.

How a 5,000-square-meter kite became a flying power plant

The core of the project is a vast wing that, at full stretch, covers a 5,000-square-meter area in the sky, making it the largest high‑altitude wind energy kite yet reported. Built under a national program, the China‑made structure is engineered to deploy fully in mid‑air, then retract on command so it can survive gusts and be reeled back for maintenance. During recent trials, the system achieved complete in‑air deployment and recovery, a key proof that such a large flexible surface can be controlled reliably at altitude.

The program is led by China Energy Engineering, which has been tasked with turning the concept into a practical generator rather than a one‑off stunt. The kite is tethered to ground equipment that converts the mechanical pull of the line into electrical power as the wing traces looping paths through the sky. By flying crosswind, the kite multiplies the apparent wind speed across its surface, which in turn increases the force on the tether and the energy that can be harvested in each cycle.

Inner Mongolia test flights and the rise of airborne wind

The first large‑scale tests took place in the wide open spaces of Inner Mongolia, where strong, consistent winds and sparse population make it an ideal proving ground. There, China successfully deployed what it describes as the world’s largest power‑generating kite, designed specifically to exploit energy‑dense high‑altitude winds. Engineers report that the system completed full flight cycles, including launch, power‑generating flight and controlled retrieval, which are all essential steps before any commercial deployment.

Those Inner Mongolia trials are part of a broader push to capture wind resources that conventional turbines cannot reach. At several hundred metres and above, the atmosphere offers stronger and more stable flows than those available to even the tallest onshore towers, and the kite is built to operate in exactly those layers. By flying in Northern China, where a high-altitude wind energy has already taken off as a demonstration of this approach, the project taps into some of the country’s best wind corridors while avoiding the land‑use conflicts that can dog large turbine farms.

Inside the “wild” capabilities: automation, altitude and energy density

What makes this super‑kite feel so radical is not only its size but the way it flies. Rather than hovering passively, the wing is guided through precise patterns by onboard controls and ground‑based software that constantly adjust its angle and trajectory. Reports on the power-generating kite describe a system that can climb to high altitudes, harvest energy in crosswind flight, then pivot into a low‑drag configuration while it is reeled back in, reducing the energy cost of each reset cycle. This pumping motion, repeated over and over, is what turns the kite into a continuous generator rather than a one‑off burst of power.

The altitude is central to its promise. By operating in upper atmospheric layers, the kite taps winds that are both stronger and more predictable than those near the surface, a point underlined in technical descriptions of high-altitude power systems. The result is a higher capacity factor, in theory, than many ground‑based turbines, which must contend with lulls and turbulence. If the control algorithms can keep the kite stable in changing weather, the platform could deliver a steadier stream of electricity than its whimsical appearance suggests.

Strategic stakes for China’s clean energy race

For Beijing, the giant kite is not a curiosity but a strategic asset in a crowded clean‑tech race. The project sits within a national effort to expand renewable capacity while reducing dependence on imported fuels, and it showcases how China is willing to back unconventional hardware when it promises a leap in performance. By pairing the kite with existing grid infrastructure in windy regions, planners hope to add flexible capacity that can be scaled up or down more easily than fixed turbine arrays.

The institutional backing is significant. The national program led by The China Energy Engineering Corp gives the technology a pathway from prototype to potential commercial rollout, including integration with large‑scale transmission projects. Analysts who track China’s energy strategy see the kite as one piece of a broader portfolio that includes ultra‑high‑voltage lines, offshore wind and massive solar bases in desert regions, all aimed at securing long‑term energy security while meeting climate commitments.

From experimental flights to future grids

The technology is still in its experimental phase, but the trajectory is clear. Earlier test campaigns confirmed that China could complete full flight cycles with the world’s largest power‑generating kite, including safe deployment and retrieval. Subsequent reports on the World’s largest high‑altitude wind energy kite taking flight in China suggest that engineers are now focused on refining control systems, improving durability and validating long‑term performance in real weather. Each successful campaign reduces the technical risk that has long kept airborne wind on the fringes of the energy sector.

If those hurdles are cleared, the implications for future grids are substantial. A mature fleet of such kites could complement conventional turbines by operating at different heights and in different wind regimes, smoothing overall output. Deployed in clusters over remote regions like Inner Mongolia and Northern China, they could feed power into long‑distance lines that move electricity to coastal cities. With China already positioning itself as a leader in high‑altitude wind power, the giant super‑kite now circling its skies offers an early glimpse of how future energy systems might look very different from the forests of steel towers that define wind power today.

More from Morning Overview