China is turning to the wild to sharpen its next generation of battlefield machines, training artificial intelligence to stalk, surround, and strike in ways that echo hawks circling prey and coyotes hunting in packs. Instead of relying only on human tactics or computer simulations, its engineers are feeding combat algorithms with lessons drawn from animal behavior to make drones, robots, and other autonomous systems faster and more unpredictable in a fight.

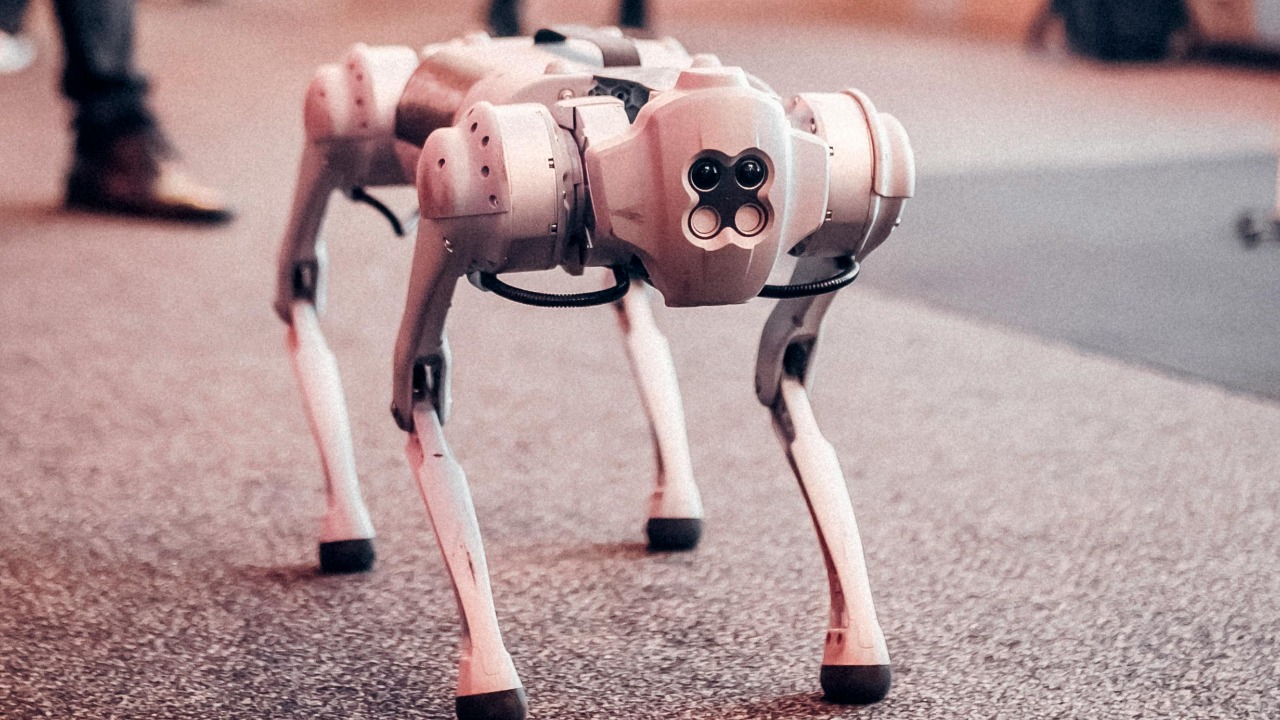

The result is a weapons program that blurs the line between biology and warfare, as swarming drones and robotic “dogs” learn to coordinate like flocks and herds while individual attack systems mimic the split‑second decisions of raptors. It is a vision of conflict where machines do not just follow orders, they adapt in real time, guided by instincts borrowed from nature’s most efficient killers.

From hawks and coyotes to battlefield code

Chinese military researchers are explicitly studying how predators select, track, and overwhelm targets, then translating those patterns into code that can guide autonomous weapons. Observing how hawks single out vulnerable prey and how coyotes cooperate to corner victims has become a template for training AI that can prioritize which enemy asset to hit first, when to break formation, and how to exploit gaps in defenses, according to observations of these programs. I see this as a deliberate attempt to give machines the kind of situational awareness that animals evolved over millions of years, but compressed into software that can be updated in weeks.

Patent filings and government tenders reviewed by outside analysts show that Patent documents are not theoretical exercises but blueprints for real systems that the People’s Liberation Army intends to field. Procurement records posted on PLA‑controlled platforms indicate that Procurement officers are already shopping for AI‑driven drone swarms that can leave the lab and operate in contested airspace, with an eye on both offense and air defense. In my view, that combination of basic research and concrete buying plans is what turns an experimental idea into a strategic shift.

Swarming drones that think like flocks and packs

Beijing’s military is concentrating on swarms of small drones that can behave like coordinated packs, picking off individual targets or saturating defenses through sheer numbers. Reporting on these programs describes how Beijing is investing in formations that can autonomously distribute roles, with some drones scouting, others jamming, and others carrying explosives. I read that as an attempt to recreate the division of labor seen in wolf packs or coyote groups, but at machine speed and scale.

In one test, attacking drones were reportedly trained to maneuver and dodge like doves as they closed in on a target, using motion patterns inspired by flocks to confuse defenses and survive incoming fire. That experiment, described in detail in accounts of Attacking formations, shows how engineers are not just copying predators but also prey, borrowing evasive maneuvers that make it harder for human operators or automated defenses to lock on. When I look at that blend of offensive and defensive mimicry, it suggests a future in which airspace is crowded with machines constantly adjusting their paths in ways that feel organic rather than mechanical.

Beyond birds and coyotes: a full menagerie of military AI

China’s animal‑inspired arsenal is not limited to raptors and canines, it extends to a broader catalog of species whose group dynamics and navigation skills can be turned into algorithms. Research linked to China’s National Defense University has examined how ants coordinate, how sheep move as a herd, how whales communicate, how eagles dive, and even how fruit flies respond to stimuli, all with the goal of improving Drones and other autonomous platforms. I see that as a systematic attempt to turn the entire animal kingdom into a reference library for swarm intelligence and target selection.

Reports on these projects note that Inside China, engineers are teaching drones to operate as kamikaze weapons in suicide attacks or as reusable strike assets that can loiter and then dive like eagles. Parallel coverage of the same research highlights that China’s research is explicitly framed as a way to refine both offensive strikes and coordinated defense, which tells me the goal is a flexible ecosystem of machines that can switch roles as fluidly as animals do in a changing environment.

Robot dogs, gun‑toting wolves and the PLA’s ground game

While the airborne swarms grab headlines, China is also fielding ground robots that borrow from canine and wolf behavior, including quadruped platforms that can carry rifles and move across rough terrain. Video investigations describe how China has rolled out an army of robots so advanced that commentators compare them to, and sometimes above, the capabilities of Boston Dynamics machines. In my reading, that comparison is less about showmanship and more about signaling that these platforms are agile enough to keep up with infantry and operate in urban environments.

Separate footage focuses on gun‑toting “robot wolves” that look like something out of science fiction but are being tested as real tools for patrols and assaults. Analysts who dissect these clips of China’s robotic wolves argue that the design is meant to evoke pack hunters, with multiple units coordinating fields of fire and flanking routes. A related breakdown of Nov demonstrations underscores how quickly these concepts are moving from test ranges into operational units, which, in my view, raises the stakes for any military that might face them in close quarters.

Strategic stakes and the race for swarm dominance

Behind the animal metaphors is a clear strategic bet: that whoever masters swarm intelligence and autonomous coordination will gain a decisive edge in future conflicts. Analysts who have reviewed Chinese documents say that China is placing significant emphasis on using AI to deploy swarms of drones, robotic dogs, and other autonomous systems, with particular focus on applications related to swarm intelligence. Additional summaries of these plans stress that China sees these technologies as central to both offensive breakthroughs and resilient defense, which I interpret as a sign that swarms are being woven into doctrine, not treated as side projects.

At the same time, there is a growing recognition that this approach carries serious risks, from accidental escalation to the temptation to hide human responsibility behind opaque algorithms. Commentators warning about these programs argue that Not only might autonomous systems make deadly mistakes, their black‑box decision making could provide cover for bad human decisions that are never fully uncovered. When I weigh those warnings against the pace of development described in Updated accounts of Beijing’s focus on swarming, it is clear to me that the world is entering a phase where the logic of the battlefield is being rewritten by code that thinks a little more like a hawk and a little less like a human.

More from Morning Overview