SpaceX is carrying out one of the most dramatic reshuffles in the short history of commercial spaceflight, pulling more than 4,000 Starlink satellites down to roughly 300 miles above Earth after a near miss with a Chinese spacecraft. The maneuver turns a single close call into a wholesale redesign of the broadband constellation’s architecture, with implications for collision risk, debris, and how low‑Earth orbit is managed. I see it as a stress test of whether mega‑constellations can adapt fast enough to the crowded skies they helped create.

At the heart of the move is a tradeoff between safety and sustainability. Dropping thousands of satellites to a lower altitude should reduce the chance of catastrophic collisions and speed up natural decay if something goes wrong, but it also tightens the orbital lanes where many other operators now want to fly. The decision, triggered by a Chinese satellite passing uncomfortably close to a Starlink unit, is already feeding a wider debate over who gets to set the rules in low‑Earth orbit and how quickly those rules need to change.

The near miss that jolted a mega‑constellation

The chain reaction began with a near collision between a Chinese satellite and a Starlink spacecraft that, according to one account, came close enough to force a rethink of how the constellation is flown. The encounter, involving a Chinese spacecraft and a Starlink device, did not result in impact, but it highlighted how quickly a crowded orbit can turn dangerous when thousands of satellites share similar paths. Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Software later analyzed the event and described it as a close call that exposed how tightly packed some of these orbits have become.

Those researchers concluded that the near miss effectively pushed Starlink into a large‑scale orbit change, framing the response as a move to “increase space safety” rather than a routine adjustment. Their study found that a Chinese satellite had, in practice, forced 4,400 of its Starlink rivals into a lower altitude band, a scale that goes far beyond the occasional avoidance burns operators typically perform. I read that as a signal that the old model of handling conjunctions one by one is breaking down when a single network already numbers in the thousands.

Dragging thousands of satellites down to 300 miles

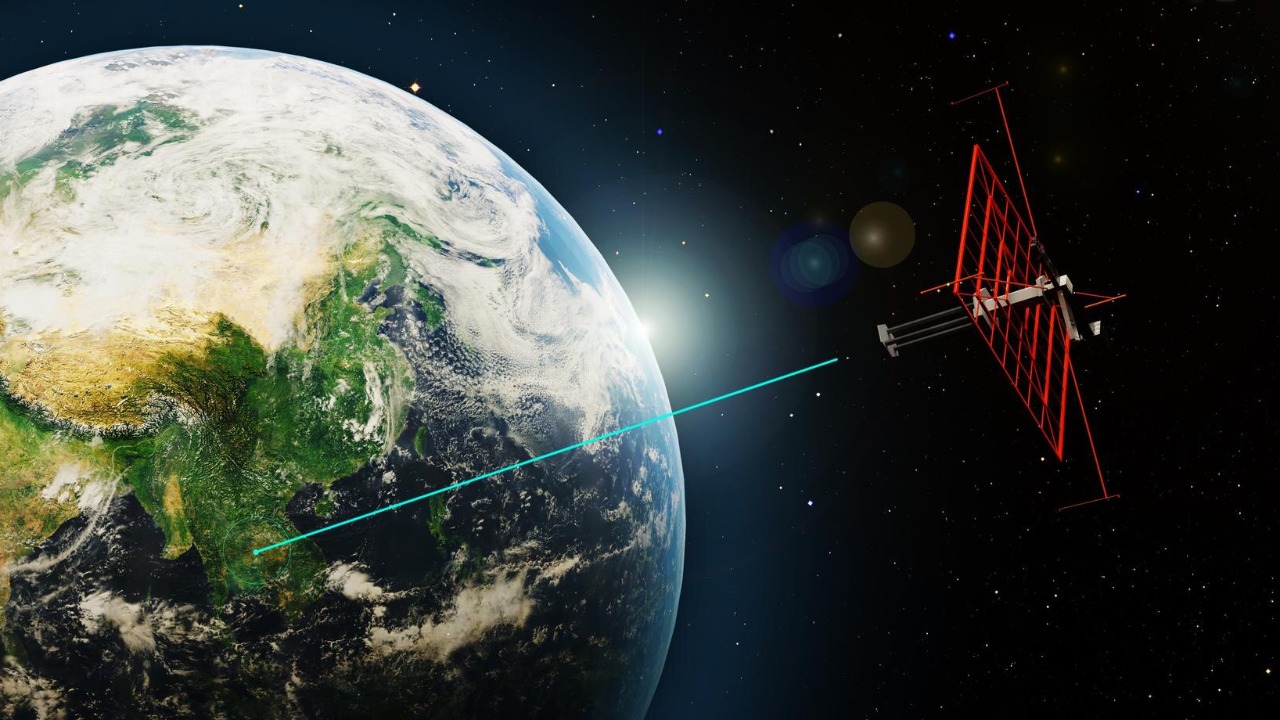

In response, SpaceX is not tweaking a handful of orbits but reconfiguring the backbone of its broadband system. Company representatives have acknowledged that more than 4,000 Starlink satellites are being shifted downward, a figure echoed in separate technical reporting that describes a plan to lower Starlink Orbits after the near miss. The target is a new shell around 300 miles, or roughly 480 kilometers, which effectively compresses a huge portion of the constellation into a tighter, lower ring around the planet.

Independent coverage of the maneuver notes that the 4,400 satellites involved represent a substantial share of the active fleet, not just a marginal slice. From an engineering standpoint, that means thousands of small ion thrusters firing in carefully choreographed sequences over months, each satellite stepping down from its previous track to the new altitude while still delivering service. I see that as a live experiment in whether a mega‑constellation can be treated as a flexible, software‑defined structure rather than a fixed layer of hardware frozen where it was first deployed.

From 550 km to 480 km, and why lower can be safer

The safety logic behind the move rests on basic orbital mechanics. Earlier plans had Starlink satellites operating around 550 km, high enough that any dead spacecraft could linger for decades. The new configuration shifts a large cohort down to about 480 km, where atmospheric drag is stronger and failed units naturally deorbit more quickly. That shorter lifetime reduces the long‑term debris burden if a satellite loses control or fragments, a key concern when thousands share similar paths.

There is a performance upside too. At 480 kilometers, signal latency improves slightly, which matters for applications like online gaming or high‑frequency trading that already lean on Starlink. The tradeoff is that satellites at this height experience more drag and need more frequent station‑keeping burns, which in turn demands careful fuel budgeting and robust propulsion. When I look at the decision to move from 550 km to 480 km, I see a bet that the operational cost of flying lower is worth the safety margin and service gains, especially as collision risks rise with every new launch.

Inside Starlink’s “explosive” fix and engineering playbook

Under the hood, the shift is being framed as a deliberate, phased campaign rather than a scramble. In a short update, Michael Nichols the engineering at SpaceX described Starlink as beginning a significant move to lower all of its satellites over the course of 2026, suggesting the near miss accelerated a plan that engineers were already modeling. That timeline aligns with other reports that the Move will see spacecraft shift shells over a few months at a time, with operators watching how the new configuration behaves before committing additional batches.

Some analysts have described the strategy as an “explosive” solution to a serious problem, a nod to commentary that SpaceX is confronting a constellation‑scale risk rather than tweaking individual orbits. One widely viewed breakdown of the situation emphasized that the issue is not Starship or the Falcon 9 launch system, which remain central to putting Starlink hardware in space, but the way the satellites themselves are arranged once they get there. I read that framing as important, because it underlines that launch reliability is no longer the bottleneck; the real challenge is managing the orbital traffic jam that success has created.

What the shift means for rivals, regulators, and the next 44,000 satellites

The consequences of this maneuver extend far beyond SpaceX. Chinese researchers have already highlighted how a single national satellite forced thousands of foreign spacecraft to change altitude, a reminder that no operator controls the orbital commons. Their study, which focused on how a Chinese satellite encounter led to 4,400 Starlink units being tightly packed into a lower band, implicitly raises questions about how future constellations from Europe, India, or Amazon’s Kuiper project will coexist in the same layers. If one network can be nudged into a wholesale redesign by another country’s spacecraft, regulators will face pressure to define clearer rules for priority, right of way, and liability.

There is also the scale of what comes next. Starlink has long talked about eventual deployments that could reach tens of thousands of satellites, with some filings referencing figures as high as 44 thousand units over time. When I map that ambition onto the current reshuffle, I see a preview of the governance challenges that will accompany any constellation of that size. Educational explainers have already started asking why Jan is the moment Starlink is lowering all of its satellites, and the answer seems clear: the system has reached a density where ad hoc coordination is no longer enough.

For now, the company line is that the large‑scale lowering is about safety and responsible stewardship, a message echoed in technical coverage that describes the effort as being carried out “for safety’s sake.” Independent analysts, including those following Follow Tom Carter and others, have noted that Elon Musk and his team are also keenly aware of the reputational risk if Starlink were involved in a major collision. As more operators crowd into low‑Earth orbit, I expect this episode to be cited in policy debates as both a warning and a template: a case where a mega‑constellation bent rather than broke when the orbital environment pushed back.

More from Morning Overview