Energy is quietly becoming the sharpest tool in global power politics, and the emerging courtship between Beijing and Brussels could redraw the map. If China and Europe lock in a deep energy pact, they would not just coordinate climate policy, they would hard‑wire a new industrial and geopolitical order around electrification and clean technology. I see the outlines of that shift already forming in trade deals, grid investments and speeches from leaders who increasingly talk about power cables and hydrogen pipelines in the same breath as security alliances.

The rise of an electrotech bloc

The strategic logic for a China‑Europe energy axis starts with simple arithmetic: both are large net importers of oil and gas, and both are racing to replace those imports with electricity generated from renewables. Analysts describe Europe and China as natural partners in an emerging “electrotech” bloc, where industrial competitiveness is defined by batteries, grids and software rather than barrels. In this vision, the power system of the future is highly electrified, with wind and solar at its core, and China is already demonstrating that such a system can coexist with a modern industrial economy, a point underlined in recent assessments of China’s energy transition.

That shift is visible in hard data. Renewables have pushed China’s fossil‑fuelled power generation into its first annual decline in a decade, even as demand for electricity keeps rising. Beijing is embedding itself across global renewable supply chains, from solar modules to grid‑connected devices, and is increasingly present in European energy system operations. If Europe chooses to lean into that reality rather than resist it, the result would be a vast, integrated market for clean technologies that could set global standards and tilt the balance of economic power away from fossil exporters.

Europe’s search for energy security and autonomy

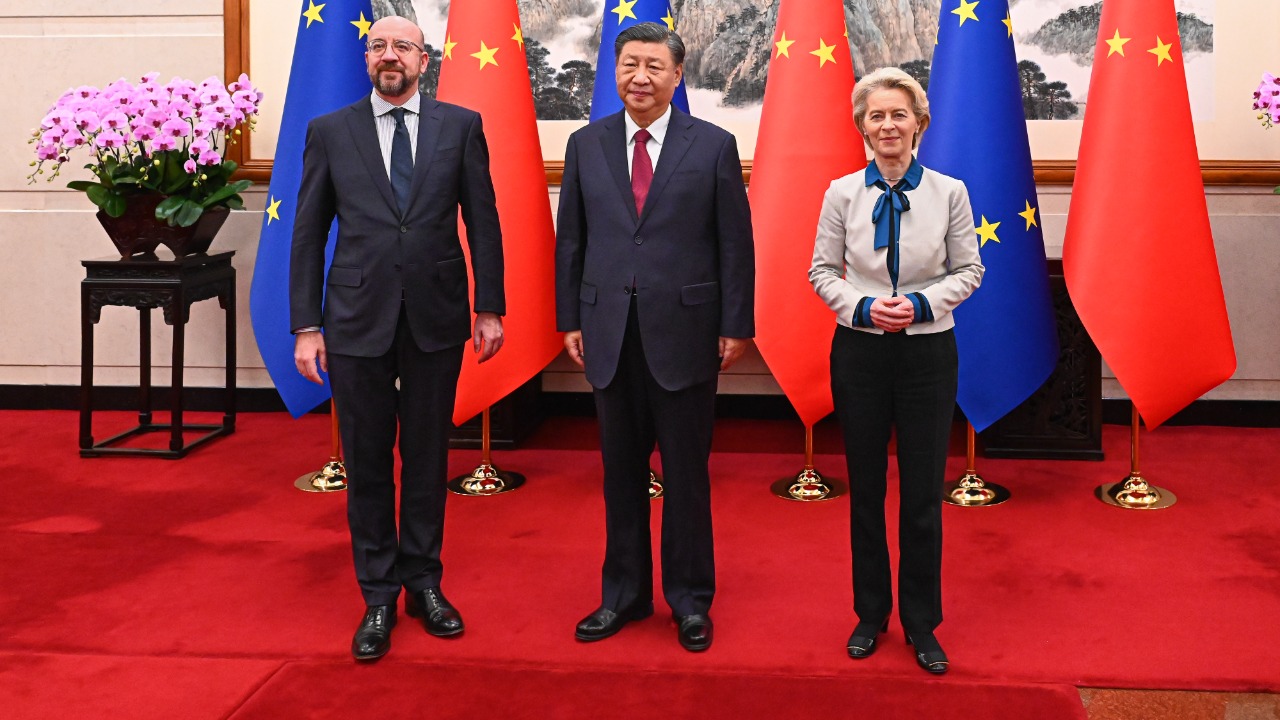

For Europe, the attraction of a deeper energy partnership with Beijing is rooted in vulnerability. The gas shock that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exposed how energy can become a chokepoint, and European leaders now talk explicitly about building an interconnected and affordable market, a “true energy union”, to protect Energy security and independence. In Davos, Ursula von der Leyen reflected on how recent crises inadvertently created the conditions for a more global outlook and a permanent change in how Europe thinks about resilience, a shift that naturally extends to who supplies its turbines, batteries and critical minerals.

At the same time, European policymakers are trying to square openness with fairness. German chancellor Friedrich Merz has argued that Europe must strengthen rules for fair trade and act as the antithesis of state‑sponsored, unfair competition, rather than retreat into protectionism and isolationism. That balancing act is visible in the European Commission’s guidance on Chinese clean‑tech imports, where officials framed a new What Is the’s approach as a Deal that preserves industrial capacity while still tapping low‑cost Chinese components. On January 12, the On January release of that guidance by the European Commission signalled that Brussels is prepared to manage, not sever, its energy‑industrial ties with Beijing.

China’s strategy: from factory of the world to grid architect

Beijing’s calculus is equally strategic. As the United States doubles down on protectionist industrial policy, China has scored big trade wins by pursuing new allies, with Beijing clinching agreements with the EU and Canada that reinforce a rules‑based trade model President Donald Trump has denounced. A separate analysis of Beijing’s outreach notes that these deals are not just about tariffs, they are about locking in long‑term demand for Chinese clean‑energy hardware and standards. In Davos coverage, one expert put it bluntly, saying China “definitely wants to assume the mantle of being the adult in the room” while the United States signals an American return to fossil fuels.

Energy is central to that repositioning. China is systematically embedding itself in global renewable energy supply chains and European grid operations, from smart meters to high‑voltage interconnectors. A detailed brief on the “dragon in the grid” warns that China is using state‑backed finance to support cross‑border projects that give its firms long‑term influence over how electricity flows across the continent. If Europe embraces a formal energy pact without robust safeguards, it could find that the architecture of its decarbonised system is effectively designed in Beijing, even as it gains cheaper hardware and faster emissions cuts.

Davos splitscreen: Trump’s fossil bet versus China‑Europe electrification

The contrast with Washington’s current posture was on vivid display in Davos. In a widely discussed “splitscreen” moment, By EMILY YEHLE reported how President Donald Trump used his appearance at the Annual Meeting of to double down on fossil fuels, even as Chinese officials highlighted their clean‑energy build‑out. The same account noted that Trump’s team has sharpened the ideological divide over climate policy, treating electrification as a threat to sovereignty rather than a source of resilience, a stance that has made it politically safer in parts of the United States to champion oil and gas than to back large‑scale renewables.

That divergence is not just rhetorical. A leaked draft of the Industrial Accelerator Act, previously known as the Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator, suggests Washington is prepared to impose strict domestic content rules that could raise costs for end consumers and further alienate allies. Against that backdrop, a China‑Europe energy pact would look less like a niche climate arrangement and more like the nucleus of a rival economic pole, one that treats electrification as the organising principle of industrial policy. In Davos commentary, observers warned that such a bloc could leave the United States increasingly isolated if it clings to a fossil‑centric model that Trump has framed as a badge of sovereignty.

Trade skirmishes, EVs and the politics of interdependence

For all the talk of alignment, the road to a stable China‑Europe energy compact runs through contentious trade politics. Earlier this year, Brussels and Beijing took a step toward resolving their dispute over electric‑vehicle tariffs, a clash symbolised by The Cupra Tavascan, an electric SUV made by Volkswagen in China and showcased in Munich. Reporting from that dispute highlighted how a spokesman for the Leonhard Simon photographed scene underscored the EU’s dilemma: it wants to protect domestic carmakers from subsidised competition while relying on Chinese factories to scale up affordable EVs fast enough to hit climate targets. A separate policy analysis framed the EU’s new guidance on Chinese exports as one of two “new wins” for Beijing, with the Deal with Canada and the reinforcing that trend.

These skirmishes feed into a broader debate inside Europe about how far to lean into partnership with Beijing. One influential essay argued that a European future involves partnering with China without paranoia or Sinophobia, while still ensuring resilience without over‑reliance. Yet a separate newsletter warned that Intensified Tensions Await–China Relations in 2026, with divergent expectations over market access and industrial policy. That tension is sharpened by the reality that China is already deeply embedded in the EU’s market and industry, particularly in energy‑related sectors.

More from Morning Overview