Inside every living cell, proteins and membranes are in constant motion, reshaping, colliding, and flexing as they keep an organism alive. That restless activity has long been treated as biological background noise, a cost of doing business for life. Now a wave of research argues that this motion is not just a side effect of metabolism but a direct source of electrical power, a hidden layer of bioelectricity that could reshape how I think about energy in biology.

By treating cell membranes as tiny, flexible generators, scientists are uncovering a mechanism that appears to convert mechanical jostling into fast electrical signals. If that picture holds up, it could change how we understand everything from nerve signaling to aging, and even open the door to devices that harvest power from the ceaseless motion of living tissue.

The surprising idea: motion itself as a power source

The central claim emerging from this research is deceptively simple: the constant motion of living cells can generate electricity just by moving. Instead of relying only on familiar biochemical pathways like adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the work suggests that the physical agitation of cell membranes can be turned into electrical energy through well known electromechanical effects. In that view, the cell surface is not just a passive barrier but an active component in the body’s power grid.

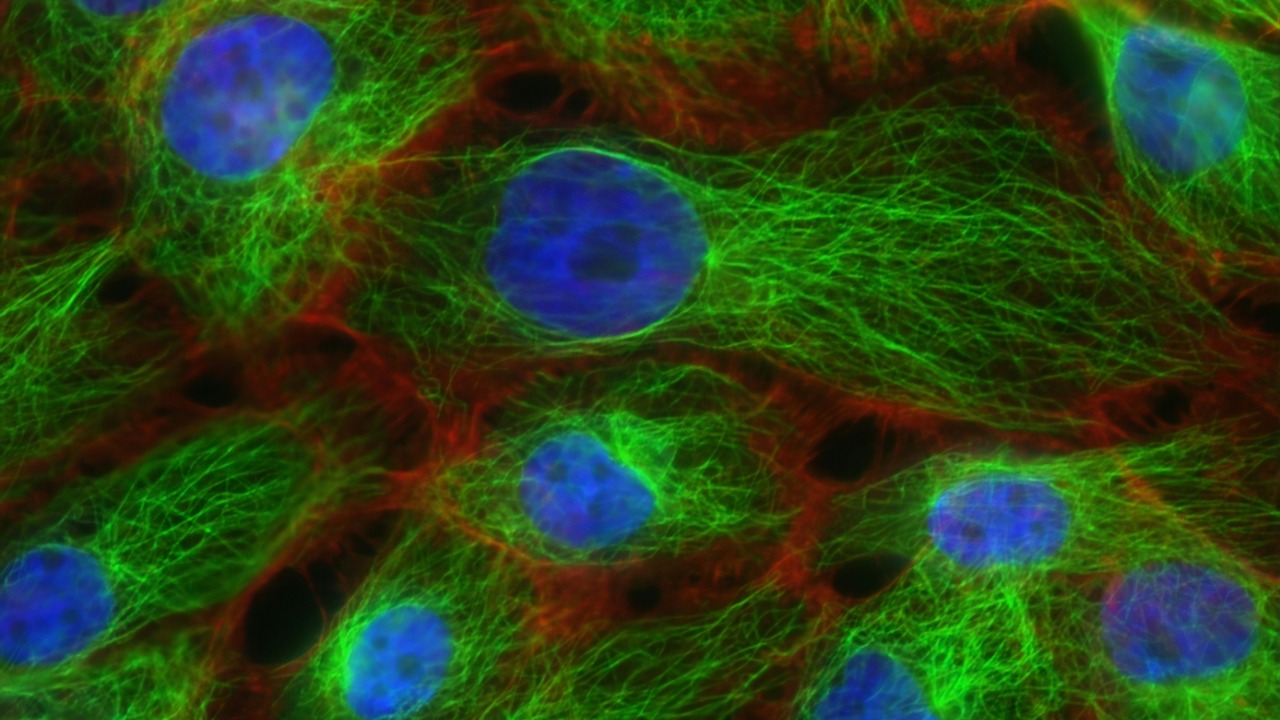

Researchers describe how the restless activity of proteins and lipids in the membrane, driven by internal metabolism, produces tiny but persistent fluctuations in shape and curvature. When those fluctuations interact with the membrane’s intrinsic electromechanical properties, they can create measurable voltages, a possibility highlighted in reporting on how the constant motion of living cells might generate electricity simply by moving.

From background noise to active bioelectricity

For decades, biophysicists have known that cell membranes are dynamic, with proteins constantly changing shape and interacting with their surroundings. That molecular bustle makes membranes ripple and flex, a phenomenon described as molecular activity that makes membranes move. Traditionally, those fluctuations were treated as thermal noise or a mechanical side effect of deeper biochemical processes, not as a functional energy source in their own right.

The new work reframes that motion as a form of “active” fluctuation, powered by metabolism and capable of doing electrical work. Instead of seeing the membrane as a passive capacitor that simply holds charge, scientists now argue that its constant reshaping can pump charge around, adding a previously unknown layer to cellular bioelectricity. That shift in perspective is central to reports that scientists have discovered evidence of previously unknown electrical power generation in living cells, suggesting that what once looked like noise may be a deliberate feature of cellular design.

Flexoelectricity: the physics hiding in plain sight

The mechanism that ties motion to electricity in these studies is a property known as flexoelectricity, where bending or curving a material generates an electric polarization. In soft biological membranes, even small changes in curvature can shift the distribution of charges across the membrane, creating tiny voltages. When the membrane is constantly flexing, those shifts can add up to a steady stream of electrical activity, effectively turning curvature into current.

Researchers argue that when active fluctuations in the membrane are coupled to this universal electromechanical property, the result is a hidden power source surrounding every cell. One team put it bluntly, saying that they show how these active fluctuations, when combined with flexoelectricity, can create a hidden source of power at the cellular boundary. That argument helps explain why the membrane, long studied for its chemical selectivity, is now being reexamined as a physical engine as well.

Evidence that cell membranes act like tiny generators

To move this idea beyond theory, scientists have developed models and experiments that treat the membrane as a flexible, electrically active sheet. By simulating how proteins and lipids jostle within that sheet, they can calculate the resulting electrical signals and compare them with measurements. Those efforts suggest that the same molecular activity that keeps membranes in motion can also drive fast voltage changes, supporting the idea that cells may generate their own electricity from motion through the work of researchers such as Liping Liu and Pradeep Sharma.

Some analyses go further, describing cell membranes as behaving like microscopic power generators that can produce rapid electrical signals without relying directly on ATP. In that picture, the membrane’s flexing can create voltage spikes that propagate faster than traditional biochemical cascades, potentially influencing how cells coordinate activity. Reporting on how cell membranes may act like tiny power generators emphasizes that these fast electrical signals could operate alongside, and sometimes ahead of, slower chemical pathways that use adenosine triphosphate to power biological work.

Why an extra layer of bioelectricity matters for the body

Bioelectricity is already central to life, from the firing of neurons to the beating of the heart and the transport of molecules across membranes. Many biological processes are regulated by electrical gradients and signals that coordinate activity across tissues and organs. New research argues that this newly described mechanism of power generation adds another layer to that system, potentially influencing how cells maintain their internal environment and respond to external cues. One report notes that many biological processes are regulated by electricity, underscoring how consequential an extra source of charge could be.

If membrane motion can generate fast, localized electrical signals, it could help explain how cells achieve rapid coordination without always invoking large, energy intensive ion flows. That might matter in tissues where timing is critical, such as the brain or heart, and in processes like wound healing where electrical cues guide cell migration. By adding a mechanical route to charge generation, the work suggests that cells have more flexibility in how they manage energy and information, blending chemical, mechanical, and electrical strategies in ways that are only now coming into focus.

Recharging aging cells and other medical possibilities

One of the more provocative implications of this research is the idea that the mechanical power of membranes could be harnessed to “recharge” aging cells. As cells grow older, their membranes and cytoskeleton often become stiffer and less dynamic, potentially reducing the active fluctuations that drive this newly described electrical mechanism. If that is true, then restoring or amplifying membrane motion might boost local bioelectricity and help maintain cellular function, a possibility that has drawn attention in coverage of a hidden source of power surrounding our cells that could be used to recharge aging human cells.

In practical terms, that could mean designing drugs or physical interventions that tweak the mechanical properties of membranes, encouraging beneficial fluctuations without damaging the cell. It might also inspire bioengineered tissues that exploit this effect to maintain their own electrical tone, improving the performance of implants or lab grown organs. While those applications remain speculative, the underlying physics offers a concrete target: enhance the coupling between active motion and flexoelectricity, and the cell’s own structure may do the rest.

Rethinking cellular energy budgets

For generations, biology textbooks have framed cellular energy almost entirely in terms of chemical fuels, especially ATP produced by mitochondria. The emerging picture of motion driven electricity does not replace that framework, but it complicates it. If membranes can convert mechanical agitation into electrical signals, then some fraction of the cell’s energy budget may be routed through this pathway, especially for tasks that require rapid, low amplitude voltage changes rather than bulk chemical work.

That possibility is central to analyses that describe how the constant motion of living cells could be a hidden source of electrical power, complementing rather than competing with ATP based metabolism. In that view, the cell uses chemical energy to drive molecular machines, those machines jostle the membrane, and the membrane in turn feeds some of that energy back into the electrical system. It is a feedback loop that blurs the line between structure and power supply.

From basic science to bioinspired technology

Beyond its biological implications, this work points toward new kinds of bioinspired devices that harvest energy from motion at very small scales. If a thin, flexible membrane can generate electricity simply by flexing, engineers might design synthetic materials that mimic that behavior, turning random motion in fluids or tissues into usable power. Such devices could, in principle, power sensors or implants that sit quietly in the body, drawing energy from the same mechanical fluctuations that animate living cells.

Some researchers already talk about this discovery as evidence of previously unknown electrical power generation

More from Morning Overview