Canada is knitting together a new generation of military and civilian satellites that can watch its territory, its skies and the space above them with unprecedented precision. The pieces range from radar platforms over the Arctic to telescopes tracking debris and asteroids, forming a surveillance web that is expanding quietly but decisively. What looks like a technical upgrade is, in reality, a strategic bet on space as the backbone of national security, climate resilience and sovereignty in the high north.

For a country with vast coastlines, sparse population and a rapidly changing Arctic, orbit is becoming the only vantage point that can cover everything at once. The emerging system is not a single program but a layered architecture of sensors, communications links and commercial constellations that together give Ottawa a far more detailed picture of what moves on, above and around its territory.

From early warning to a full-spectrum space posture

Canada’s space surveillance story began as a modest contribution to allied early warning, but it is now evolving into a full-spectrum posture that reaches from low Earth orbit to deep space. The country’s first dedicated tracking satellite, Sapphire, was designed to feed data into The US SSN, the Space Surveillance Network operated by NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command. That partnership gave Canadian operators a front row seat on how orbital traffic, from defunct rockets to active spy satellites, is catalogued and monitored in real time.

Building on that experience, defence planners set a clear Objective for the Surveillance of Space 2 project, often shortened to Surveillance of Space, which is to meet national Space Situational Awareness, or SSA, requirements while still feeding allied networks. In practice, SSA means knowing which objects are in orbit, who controls them and whether they pose a threat to Canadian assets or territory. It is a technical mission, but it also signals a political choice to treat space as a domain where Canada is not just a customer of allied data but a producer of its own.

Arctic sovereignty drives a new orbital buildout

No region shapes Canadian space policy more than the far north. There has been a long history of research and development geared towards surveillance efforts in the Canadian Arctic, where melting sea ice is opening new shipping lanes and raising fresh security concerns. Analysts have warned that Canada’s Arctic surveillance is at risk if satellite coverage gaps are not closed, and The Canadian government has acknowledged that its existing constellation cannot fully track and characterize ships and aircraft across the region’s vast distances.

That recognition is driving a wave of investment. Ottawa has signed a new strategic partnership with Canadian firms Telesat and MDA to develop military satellite communications tailored to the Arctic, giving the Canadian Armed Forces in the Arctic more reliable links for operations and surveillance. At the same time, defence planners are leaning on satellites as the backbone of an Arctic surveillance strategy that is expected to be interoperable with the U.S. Department of Defense and NATO, tying northern monitoring directly into allied command structures through a new system of sensors.

Radar, telescopes and micro-satellites: the quiet hardware surge

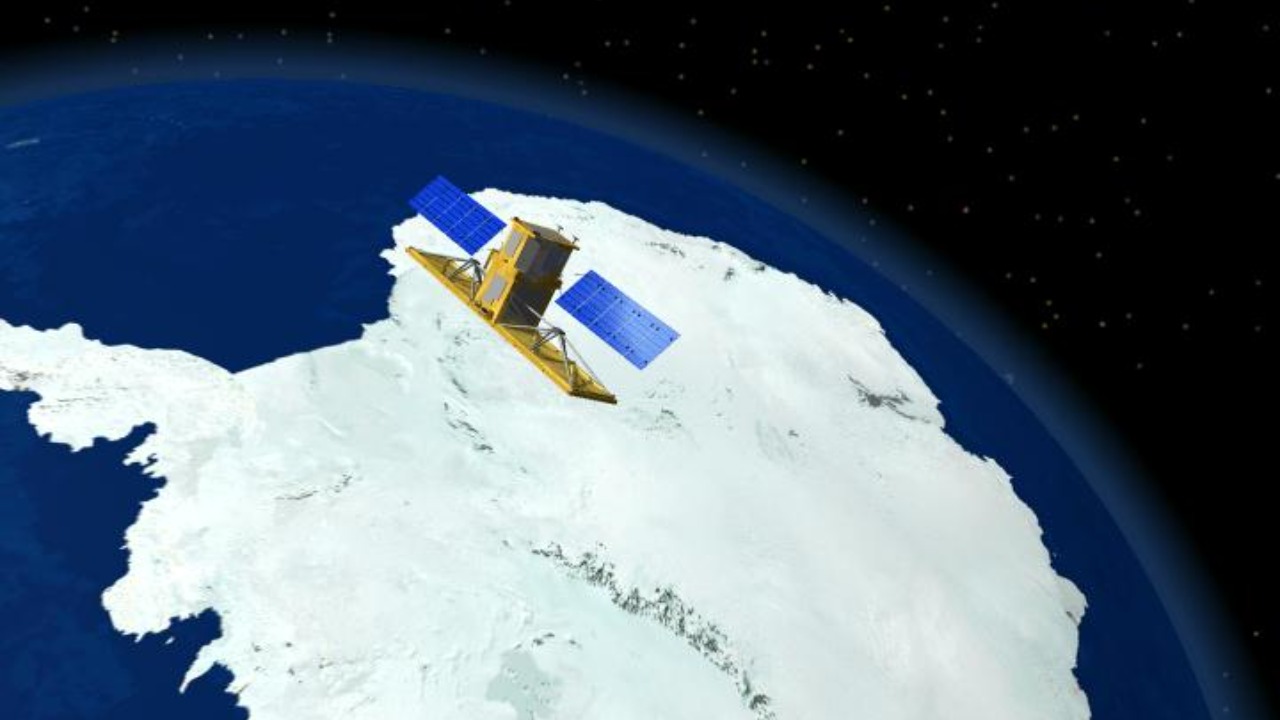

Behind the policy language is a concrete hardware surge that is reshaping Canada’s presence in orbit. The country’s radar legacy is anchored in RADARSAT, a family of satellites that used synthetic aperture radar, or SAR, to deliver detailed images regardless of cloud cover or darkness. Operating for 17 years, RADARSAT-1 helped make Canada a leader in satellite radar technology, and its successors now underpin everything from ice monitoring to maritime surveillance.

Newer platforms are smaller and more specialized. The Canadian military has ordered a space surveillance micro satellite that will complement the RADARSAT Constellation Mission satellite, a move that signals a shift toward agile, rapidly deployable sensors rather than a handful of large buses. That micro satellite order, detailed in defence reporting that notes how buyers can Get more technical specifics through subscription services, fits a broader pattern of dispersing surveillance across many nodes to make the system more resilient to attack or failure.

NEOSSat and the rise of orbital “sentinels”

Canada is not only watching Earth from space, it is also watching space itself. Known as Canada’s “Sentinel in the Sky”, NEOSSat is described as the world’s first experimental microsatellite designed to detect and track space objects and near-Earth asteroids. Launched as a compact telescope, it was built to operate 24/7, scanning for debris and celestial bodies that could threaten satellites or, in rare cases, the planet. That dual role, part planetary defence and part orbital traffic control, reflects how tightly linked civilian science and military awareness have become.

The national space agency highlights that Canada uses NEOSSat to observe asteroids, space debris and even exoplanets, turning a defence-oriented platform into a scientific workhorse. Earlier reporting on the mission emphasized that it is Known as a pathfinder for future space telescopes, showing how a relatively low cost microsatellite can deliver high value surveillance. In effect, NEOSSat and its successors are teaching Canadian engineers how to build orbital sentinels that can be repurposed quickly as threats and priorities change.

NORAD modernization and the Defence Enhanced Surveillance from Space pivot

Modernizing NORAD has become a central driver of Canada’s space surveillance agenda. The Defence Enhanced Surveillance from Space project, or DESSP, is explicitly framed as part of NORAD modernization and is listed as a Project Type that will Project Replace earlier systems. Its stated Objective is to replace and improve upon the defence capabilities delivered by previous satellite subsystems, giving commanders more timely and precise data on what is happening in and around North America.

That pivot is not happening in isolation. Analysts of Arctic security note that Canada’s first efforts towards satellite surveillance were tied to monitoring the high north, and that Jan discussions inside The Canadian defence community have focused on whether existing Arctic capabilities are enough to defend sovereignty. The DESSP architecture is meant to close those gaps by fusing radar, optical and communications payloads into a more integrated picture, one that can be shared seamlessly with NORAD and other allies through the Arctic surveillance network.

More from Morning Overview