Planet formation used to sound straightforward: dust clumps into rocks, rocks grow into worlds, and the rest is detail. A cluster of recent discoveries has shattered that tidy picture, revealing newborn planets that are swollen, distorted and in some cases forged from the wreckage of dead stars. Together, they point to a strange transitional phase that may finally explain how the galaxy’s most common planets come into being.

I see a pattern emerging from these oddities, from a lemon-shaped world to bloated young giants and even a potentially spectacular sungrazing comet. Each object looks like an outlier on its own, but taken together they sketch a missing chapter in the story of how planetary systems, including our own, are assembled.

The lemon-shaped world that blurs planet and star

One of the strangest finds to crystallize this new picture is an oblong exoplanet that looks more like a squeezed lemon than a sphere. Astronomers describe this object as so distorted that it “blurs the line” between a planet and the compact stellar remnants that usually sit at the hearts of extreme systems. Reporting on the discovery notes that it may actually be made from a former star, a body that has been stripped and reshaped until it behaves more like a planet than a sun, a scenario that pushes the definition of what a planet can be and forces modelers to rethink how such hybrids form in the first place, as highlighted in coverage by Jan and By Devika Rao in The Week US on the lemon-shaped exoplanet.

The object’s elongated shape is not just a visual curiosity, it encodes the violence of its history. Tidal forces from a nearby compact companion appear to have stretched the planet, while intense radiation scours its surface and may be driving off material in focused streams, likened to beams from a lighthouse. That combination of extreme tides and erosion is exactly the kind of environment where a star’s outer layers could be peeled away, leaving behind a dense core that masquerades as a planet. In that sense, this lemon-shaped body is a natural laboratory for testing how far stellar remnants can be recycled into planetary building blocks, and it hints that some of the “planets” we catalog around exotic stars may actually be the fossil hearts of once-larger suns.

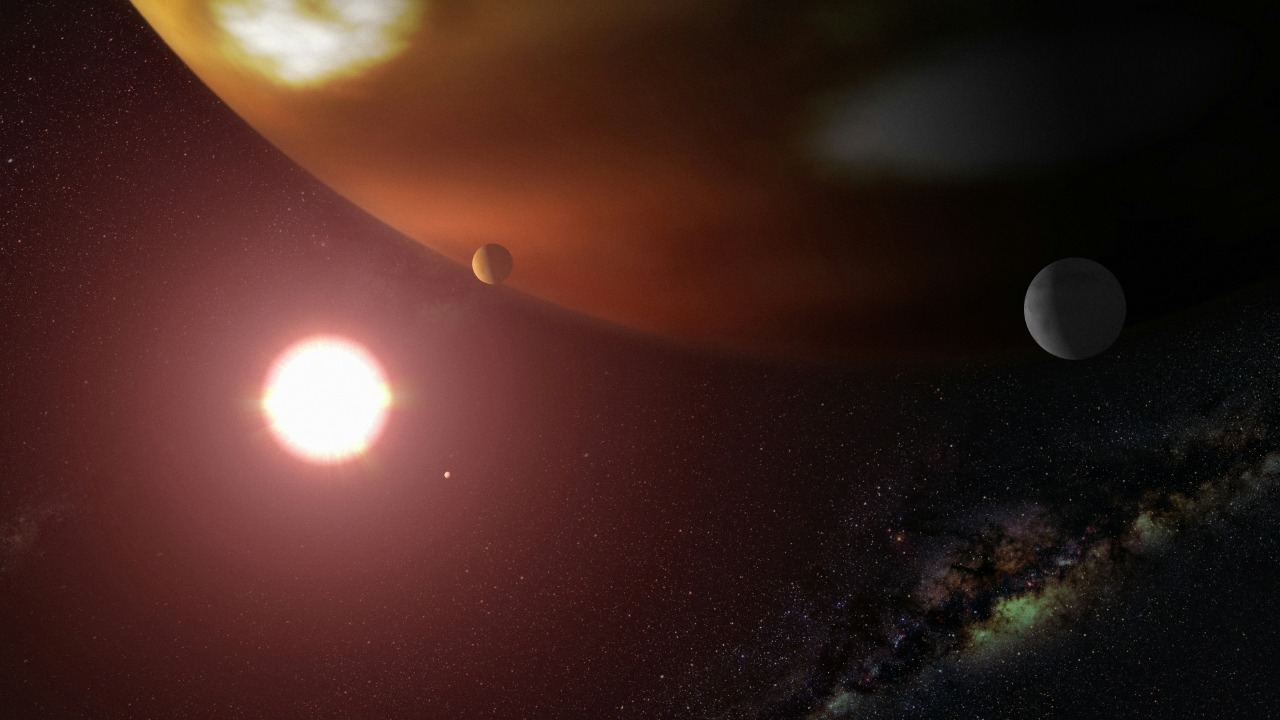

Newborn giants caught in a swollen childhood

If the lemon-shaped object shows how planets can emerge from stellar debris, a different set of observations captures planets in a more conventional but equally bizarre infancy. An international team has weighed four newborn planets in the V1298 Tau system and found that they are far larger than their eventual adult size, a result that researchers describe as a crucial missing link between young gas-rich worlds and the compact mini-Neptunes that dominate exoplanet surveys. These four bodies, each between 5 and 10 Earth radii today, are expected to shrink dramatically as they cool and lose atmosphere, a process that connects their current bloated state to the smaller, denser planets that populate the galaxy, according to detailed analysis of the galaxy’s most common.

The same system has been described as a snapshot of the strange childhood of the galaxy’s most numerous planets, the sub-Neptunes that sit between Earth and Neptune in size. By catching V1298 Tau at this early stage, astronomers can see how thick hydrogen and helium envelopes gradually contract, turning puffy young giants into the compact worlds that surveys like Kepler and TESS find in abundance. Reporting on this work emphasizes that the planets’ current radii, combined with their measured masses, imply low densities that will not last, reinforcing the idea that most planets are born oversized and then sculpted by time, stellar radiation and internal cooling, a narrative that is central to the description of how galaxy’s most common evolve.

The “missing link” phase between gas balls and mini-Neptunes

The V1298 Tau results do not stand alone. A separate study of four young planets has been described as a direct observation of the transitional phase between gas-rich proto-worlds and the compact mini-Neptunes that dominate close-in orbits. Researchers found that these planets, currently 5 to 10 times Earth’s radius, will contract as they shed mass and cool, eventually ending up only 2 to 4 Earth radii across. They argue that this evolution is driven by the loss of thick primordial atmospheres under intense stellar radiation, a process that naturally explains why so many mature systems are packed with smaller sub-Neptunes rather than giant gas balls, a conclusion summarized in work that notes how these planets will shrink from their current Earth radii.

Another analysis goes further, suggesting that most planets in our galaxy are born “bloated,” with thick gaseous envelopes that make them much larger than their final size. According to this research, the typical outcome of planet formation is not an Earth-like rocky world, but something closer to a mini-Neptune, a planet between Earth and Neptune in size that starts off swollen and then contracts. The study argues that this early inflation is a natural consequence of how planets accrete gas from their natal disks and then cool, and it frames the V1298 Tau system and similar finds as the long-sought missing link that connects theoretical models to the compact sub-Neptunes we actually observe, a point underscored in coverage of how most planets are born.

When I put these strands together, the emerging picture is that planetary systems spend a brief but dramatic phase dominated by oversized, low-density worlds that are still shedding heat and atmosphere. That phase is short-lived on cosmic timescales, which explains why it has been so hard to catch in the act. The recent detections of swollen young planets, combined with the lemon-shaped object that may be a stripped stellar core, suggest that the path from gas and dust to stable worlds is far more chaotic and varied than the neat diagrams in textbooks, a conclusion echoed in descriptions of a crucial missing link in planet formation.

Oddball systems that defy neat categories

While these young planets clarify one part of the story, other discoveries highlight just how messy planetary systems can be. Astronomers have identified a set of galaxies so peculiar that they have been likened to a platypus, the famously hard-to-classify mammal. Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, a team has found nine galaxies whose properties do not fit standard categories, including one labeled Galaxy CEERS 4233-42232, whose spectrum shows a pronounced narrow peak that resembles a quasar in some ways but not others. The comparison of this galaxy’s light to a quasar spectrum reveals features that astronomers had not been able to see before, underscoring how new instruments are exposing transitional objects that bridge previously separate classes, as shown in the detailed Image of Galaxy CEERS 4233-42232.

The same Webb observations describe these nine galaxies as so odd that they are difficult to categorize at all, hence the “platypus” nickname. They combine traits of star-forming galaxies, quasars and other active systems in ways that challenge existing labels, much as the lemon-shaped exoplanet challenges the boundary between planets and stellar remnants. For me, the lesson is that astronomy is entering an era where hybrid and transitional objects are no longer rare curiosities but central to understanding cosmic evolution, a shift captured in the description of how Astronomy has found a “platypus” population with NASA’s Webb Telescope.

From tight orbits to sungrazing comets: extreme laboratories for planet birth

Closer to home, another line of research is reshaping how I think about planetary systems by focusing on worlds in extremely tight, Mercury-like orbits. A recent study describes a strange discovery that scientists say fundamentally changes how we think about planetary systems, identifying exoplanets that occupy searingly close paths around their stars. These objects, locked into tight, short-period orbits, experience intense radiation and tidal forces that can strip atmospheres, melt surfaces and even erode their rocky cores, making them natural testbeds for the processes that turn bloated young planets into compact remnants, a point emphasized in reporting on the Strange systems with tight, Mercury-like orbits.

More from Morning Overview