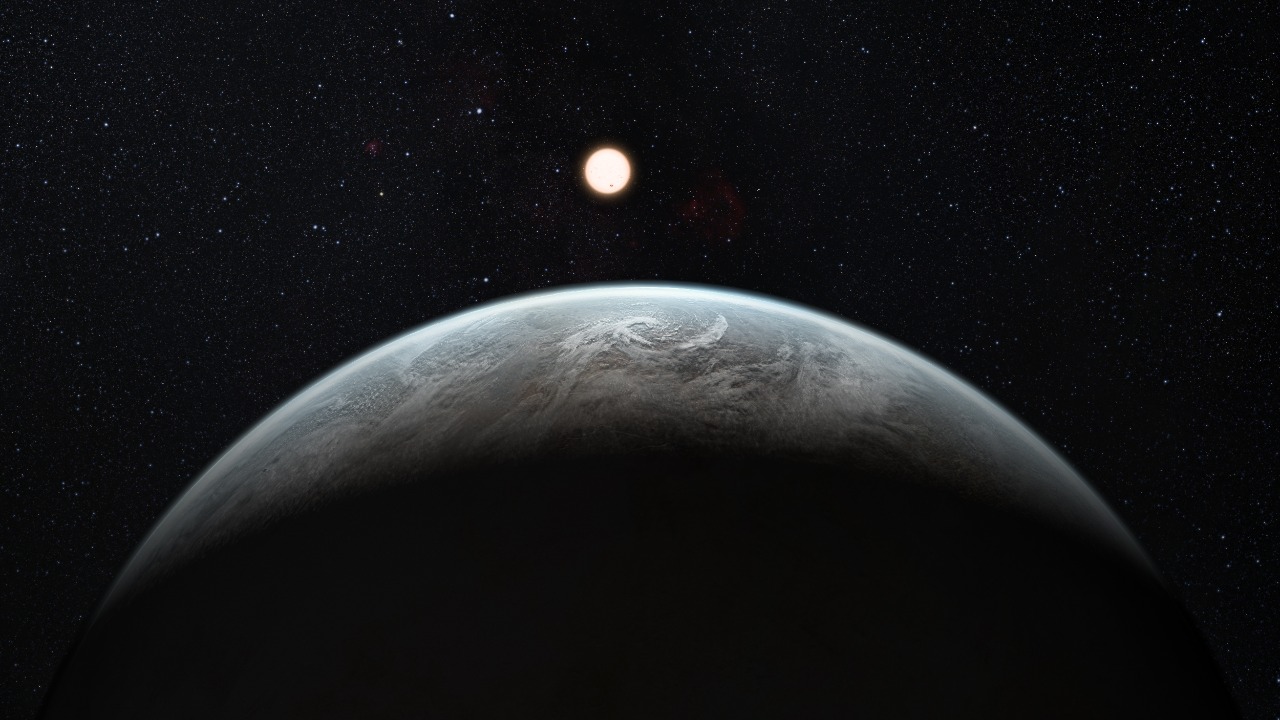

Astronomers have identified a nearby “super-Earth” that sits in the temperate zone of its star, instantly vaulting it into the short list of worlds that might be able to support life. The planet, known as GJ 251 c, orbits a small red dwarf just 18 light years away, close enough that current and upcoming telescopes can begin probing its atmosphere for signs of habitability. For researchers who have spent decades cataloging distant, hostile exoplanets, this one stands out as a rare and promising target.

Unlike many earlier discoveries that were either too hot, too cold, or too far away to study in detail, GJ 251 c combines a relatively gentle orbit with a location in our cosmic neighborhood. That combination turns a speculative search for “Earth-like” worlds into a concrete observing campaign, with scientists already mapping out how to test whether this rocky planet could actually host liquid water and, potentially, life.

What astronomers found around the star GJ 251

The new world orbits the red dwarf star GJ 251, a relatively cool and dim star in the constellation Canis Minor that lies only 18 light years from the Sun, a distance that makes it one of the closest potentially habitable planets known. Researchers classify the planet as a super-Earth because its mass and size are larger than Earth’s but still far below those of ice giants like Neptune, a category that often points to a rocky composition rather than a thick, gaseous envelope. Early measurements indicate that GJ 251 c circles its star at a distance that allows starlight to warm its surface without blasting away any atmosphere, a balance that immediately drew attention from exoplanet teams.

Evidence for the planet emerged from precise monitoring of the star’s light and motion, which revealed the subtle gravitational tug of an orbiting body with a regular period. By combining those measurements with models of red dwarf systems, astronomers concluded that GJ 251 c is a compact, likely rocky world that completes an orbit in a matter of weeks while still remaining in the star’s temperate zone, a configuration that several independent teams have now highlighted as a prime candidate for follow-up observations in the search for life beyond the Solar System, including detailed coverage in recent news reports.

Why GJ 251 c is labeled a “super-Earth”

Calling GJ 251 c a super-Earth is not a marketing flourish, it reflects a specific range of planetary mass and radius that sits between Earth and Neptune. Planets in this category are thought to be large enough to hold onto substantial atmospheres but small enough to avoid becoming gas giants, which makes them compelling places to look for rocky surfaces, oceans, and climates that might resemble scaled-up versions of our own world. In the case of GJ 251 c, the inferred mass and orbital characteristics point strongly toward a dense, terrestrial planet rather than a mini-Neptune swaddled in thick hydrogen and helium.

That distinction matters because the physics of super-Earths suggests they can sustain long-lived geologic activity and potentially stable climates, both of which are considered important ingredients for life. Modeling work tied to the discovery indicates that GJ 251 c likely falls into the mass range where plate tectonics and volcanic outgassing could help regulate atmospheric composition over billions of years, a scenario that has been emphasized in technical summaries of the find and in broader explainers on why this super-Earth stands out from the hundreds of less promising exoplanets already cataloged.

Orbiting in the habitable zone of a red dwarf

The most tantalizing feature of GJ 251 c is its position in the so-called habitable zone, the orbital band where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. Because GJ 251 is a red dwarf that emits less energy than the Sun, this zone lies much closer to the star, so GJ 251 c completes a tight, relatively fast orbit while still receiving a level of radiation that models suggest could support temperate conditions. That combination of a short orbital period and a potentially mild climate gives astronomers frequent opportunities to observe the planet as it passes in front of or tugs on its star.

Red dwarfs can be volatile, with stellar flares that strip atmospheres or sterilize surfaces, so the habitability of planets around them is not guaranteed. However, the available data indicate that GJ 251 is comparatively quiet, and climate simulations for GJ 251 c show that, with a suitable atmosphere, the planet could maintain surface temperatures compatible with liquid water across a wide range of compositions. Those conclusions underpin the description of GJ 251 c as a “potentially habitable” world in technical briefings and in public-facing coverage that highlights its orbit in the habitable zone of a nearby red dwarf.

A prime target in the search for alien life

What elevates GJ 251 c from an interesting data point to a headline-grabbing discovery is its value as an observational target in the broader search for life. At just 18 light years away, the planet is close enough that current and upcoming instruments can begin to tease out details of its atmosphere, surface conditions, and potential biosignatures. That proximity also means that even modest telescopes can contribute to long-term monitoring campaigns, turning GJ 251 c into a kind of laboratory for testing theories about how super-Earths evolve and whether they can actually host life-bearing environments.

Researchers at major observatories have already flagged GJ 251 c as a priority for spectroscopy, which can reveal the fingerprints of molecules like water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and oxygen in a planet’s atmosphere. The combination of a nearby star, a relatively large planetary radius, and a temperate orbit makes those measurements more feasible than for many other candidates, a point that has been underscored in institutional briefings that describe the planet as a prime target in the search for alien life and a benchmark for future exoplanet surveys.

How astronomers detected GJ 251 c

GJ 251 c did not appear as a bright dot in a telescope image; instead, astronomers inferred its presence from the subtle effects it has on its host star. By tracking tiny shifts in the star’s spectrum and brightness over time, teams were able to measure the gravitational pull of an orbiting planet and, in some cases, the slight dimming that occurs when the planet crosses in front of the star from our point of view. These techniques, known as radial velocity and transit photometry, have become the workhorses of exoplanet discovery, and they were applied intensively to GJ 251 once initial hints of a planet emerged.

Follow-up observations refined the planet’s orbital period, mass, and likely position within the star’s habitable zone, while cross-checks with archival data helped rule out stellar activity as a false signal. The result is a robust detection that has been detailed in technical notes and translated for a wider audience in coverage that walks through how astronomers identified the super-Earth GJ 251 c using a combination of precision spectroscopy and long-baseline monitoring of its nearby red dwarf host.

What we know, and do not know, about its potential habitability

Despite the excitement, GJ 251 c remains a distant point of light, and many of the qualities that matter most for life are still unknown. Astronomers do not yet have a direct measurement of its atmospheric composition, surface pressure, or the presence of oceans or continents, all of which will require years of follow-up work with powerful telescopes. Even the planet’s exact radius and density carry uncertainties that leave room for different interior structures, from a dry, rocky world to one with significant water content or a thick, insulating atmosphere.

What the current data do provide is a set of boundary conditions that make habitability plausible rather than purely speculative. The planet’s orbit, estimated mass, and stellar environment are all consistent with scenarios in which liquid water could exist on the surface, especially if the atmosphere contains greenhouse gases that moderate temperature extremes. Scientists are careful to stress that this does not mean life is present, only that GJ 251 c has cleared the first, stringent filters that most exoplanets fail, a nuance that is reflected in reporting that describes astronomers as eyeing the super-Earth as a potential home for life while emphasizing the need for more data.

Why proximity matters for future telescopes

The distance to GJ 251 c, just 18 light years, is not a trivial detail, it is central to why astronomers are so enthusiastic. Light from such a nearby system is bright enough that instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope and its successors can, in principle, separate the faint signal of the planet from the glare of its star. That separation is essential for spectroscopy, which relies on capturing and dispersing the planet’s light to identify atmospheric gases and possible chemical imbalances that might hint at biological activity.

In practical terms, a closer planet means shorter exposure times, higher signal-to-noise ratios, and more opportunities to observe multiple orbits, all of which improve the odds of detecting subtle features in the data. This is why GJ 251 c has quickly joined a small group of nearby, potentially habitable exoplanets that are shaping the design and observing strategies of future missions, a point underscored in analyses that highlight how a super-Earth in the habitable zone just 18 light years away can serve as a cornerstone target for the next generation of space telescopes.

GJ 251 c in the growing catalog of nearby exoplanets

GJ 251 c does not exist in isolation; it joins a growing roster of nearby exoplanets that collectively map out the diversity of planetary systems in our galactic neighborhood. Over the past decade, astronomers have identified rocky worlds around stars like Proxima Centauri and TRAPPIST-1, each with its own mix of promising and problematic traits. What sets GJ 251 c apart is the combination of a relatively calm host star, a well-placed orbit, and a mass that strongly suggests a solid surface, all within a distance that makes detailed characterization feasible.

Comparative studies of these systems are already underway, with researchers using them to test how factors like stellar activity, planetary mass, and orbital configuration influence the prospects for habitability. In that context, GJ 251 c functions as both a new data point and a benchmark, helping refine models that will guide where telescopes look next and how they interpret what they see, a role that has been highlighted in technical commentary and in accessible explainers that describe how scientists just found a super-Earth exoplanet only 18 light years away that could reshape the shortlist of worlds most likely to reward intensive study.

Next steps: probing the atmosphere and climate

The immediate scientific priority is to determine whether GJ 251 c has an atmosphere and, if so, what it is made of. Transit spectroscopy, which analyzes starlight filtered through a planet’s atmosphere as it passes in front of its star, offers one route, while direct imaging and thermal phase curves provide complementary ways to infer temperature patterns and possible cloud cover. Each method is technically demanding, but the planet’s size and proximity make them more achievable than for many other candidates that lie tens or hundreds of light years away.

Teams are already proposing observing campaigns that would search for key molecules like water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and ozone, as well as broader signatures of atmospheric escape or surface oceans. The results will not only clarify GJ 251 c’s own status but also feed back into models of how super-Earths form and evolve around red dwarfs, sharpening the criteria used to judge future discoveries. That feedback loop, in which one nearby planet informs the entire field, is a recurring theme in coverage that frames GJ 251 c as a nearby super-Earth that could have the right conditions for life and, just as importantly, could teach astronomers how to recognize those conditions elsewhere.

The broader stakes of finding a world like this

Beyond the technical details, the discovery of GJ 251 c speaks to a deeper shift in how humanity approaches the question of life beyond Earth. For much of the twentieth century, that question was largely philosophical, with little data to constrain the possibilities. Now, with a growing list of nearby, potentially habitable planets, it is becoming an empirical problem that can be tackled with telescopes, spectra, and statistical models, and GJ 251 c is one of the clearest examples of that transition from speculation to measurement.

If future observations reveal an atmosphere rich in water and other life-friendly molecules, GJ 251 c will become a focal point for discussions about how common habitable worlds might be in the Milky Way. Even if the planet turns out to be barren or hostile, the lessons learned from studying it will refine the search, helping scientists distinguish between worlds that only look promising on paper and those that truly have a chance to host biology. That dual role, as both a candidate for habitability and a test case for the methods used to assess it, underpins descriptions of GJ 251 c as one of the best chances to find life among the exoplanets discovered so far, and it is why this unassuming red dwarf system has suddenly become a central focus of the search for life beyond our own world.

More from MorningOverview