Warnings from one of artificial intelligence’s most influential pioneers are colliding with a harsh business reality: most corporate AI projects already fail. When the so‑called “godfather of AI” argues that today’s large language model tools are structurally misaligned with how companies actually work, he is not just sounding an abstract alarm about future risks. He is describing why so many expensive deployments are quietly collapsing before they ever deliver value.

I see a widening gap between the hype around generative AI and the way these systems behave in real organizations, where accuracy, accountability and security matter more than flashy demos. That gap, highlighted by Geoffrey Hinton’s recent critiques, helps explain why executives keep pouring money into LLM pilots that stall, underperform or get shut down once they hit real‑world constraints.

Why the “AI godfather” is skeptical of corporate LLM hype

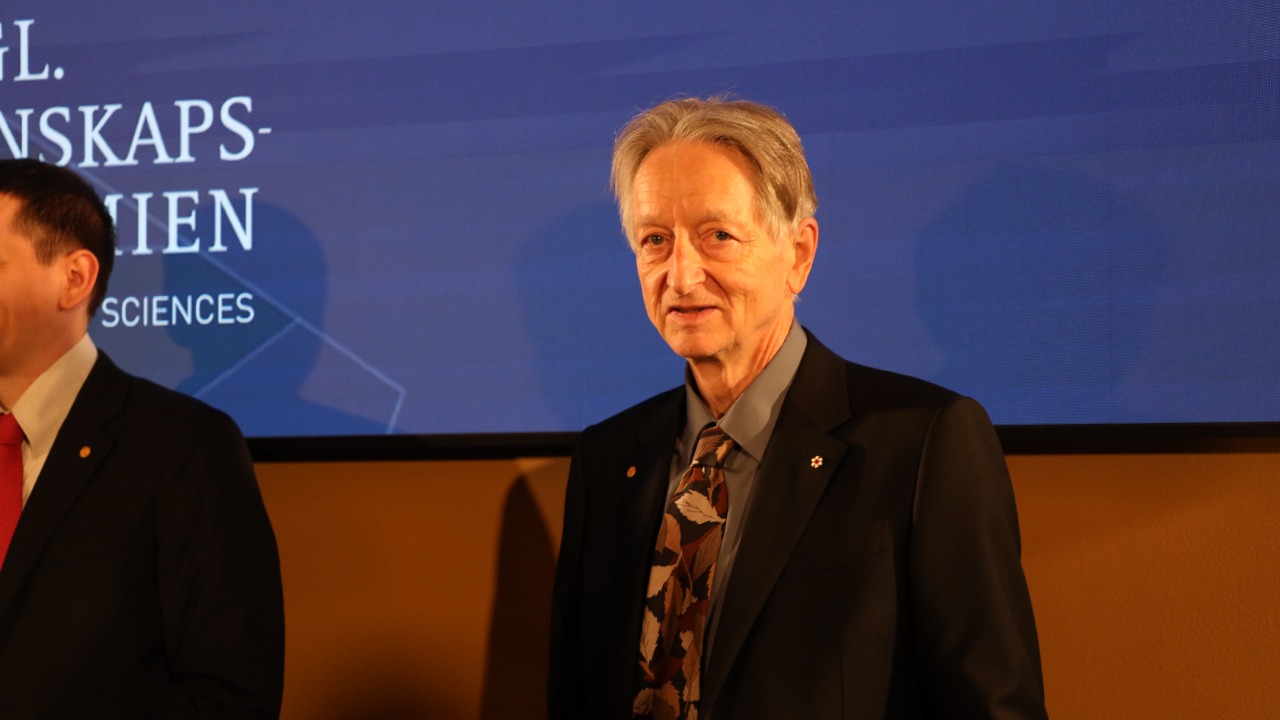

Geoffrey Hinton has spent decades building the neural network techniques that underpin today’s large language models, which makes his skepticism about their business utility especially striking. In recent public remarks, he has argued that the current generation of generative systems is fundamentally unreliable, prone to fabricating details and difficult to align with human values at scale. When a model is optimized to predict the next word rather than to verify facts or respect internal policies, I find his point hard to ignore: it will eventually collide with the compliance and audit demands that define serious enterprise software.

Hinton has also criticized the way major technology companies are racing to commercialize these systems while, in his view, downplaying their systemic risks. In one interview, he warned that many tech leaders are not taking long‑term dangers seriously enough, even as they push LLM‑powered products into sensitive domains like healthcare, finance and public services. His concern is not only existential; it is operational. A tool that can confidently generate incorrect medical advice or misinterpret a financial regulation is not just philosophically troubling, it is a liability. That tension runs through his recent comments in videos such as this discussion, where he stresses how hard it is to control systems whose internal reasoning we do not fully understand.

Most AI projects already fail, and LLMs raise the stakes

The scale of failure in corporate AI initiatives is not speculative. Industry research has found that more than 80 percent of AI projects never make it into production or fail to deliver meaningful business impact, wasting billions of dollars in sunk costs. When I look at that figure, it is clear that the problem predates the current LLM wave, but generative tools amplify the same structural weaknesses: unclear objectives, poor data foundations and a rush to deploy technology before defining how it will actually change workflows.

Those numbers matter because they show how fragile AI business cases already are before companies layer in the added complexity of large language models. An LLM that drafts marketing copy or summarizes customer calls might look impressive in a pilot, yet still fail to clear the bar for reliability, security or return on investment once procurement, legal and risk teams get involved. The research on AI project failure underscores how often organizations underestimate integration costs and overestimate short‑term gains, a pattern that is even more pronounced when the system’s behavior is probabilistic and hard to predict.

Hallucinations, liability and the limits of “good enough”

At the heart of Hinton’s warning is a technical reality that many business pitches gloss over: large language models do not “know” things in the way humans do, they generate plausible continuations of text based on patterns in their training data. That design makes hallucinations, the confident invention of facts, a feature of how they operate rather than a rare bug. In a consumer chatbot, a made‑up restaurant review might be annoying. In a bank’s compliance tool or a hospital’s triage assistant, it can be catastrophic.

In several talks, including one widely shared lecture, Hinton has emphasized how difficult it is to guarantee that such systems will not produce harmful or misleading outputs, even with extensive fine‑tuning and guardrails. From a business perspective, that uncertainty translates directly into legal and reputational risk. I see many vendors arguing that “human in the loop” review will catch the worst errors, but in practice, overworked staff quickly start to trust the system’s apparent fluency. The more polished the output, the harder it becomes to maintain healthy skepticism, which is precisely why Hinton’s focus on alignment and control resonates so strongly in regulated industries.

Leadership blind spots and the one figure who “gets it”

Hinton’s critique is not limited to the technology itself; it extends to the people steering it. He has said that most senior executives at major technology firms are inclined to minimize AI’s long‑term risks, framing them as distant or speculative while prioritizing short‑term market share. That attitude filters down into product roadmaps that treat safety and robustness as add‑ons rather than core design constraints. When I listen to his interviews, I hear frustration with leaders who, in his view, are repeating the pattern of deploying powerful systems first and worrying about consequences later.

At the same time, Hinton has pointed to at least one prominent figure he believes takes the dangers more seriously, describing this person as unusually willing to confront uncomfortable scenarios about where advanced AI could lead. In coverage of his comments, he contrasts that stance with what he sees as a broader culture of downplaying risk among other tech elites. Reports on his remarks, including one focused on how he views tech leaders, highlight his view that genuine engagement with worst‑case outcomes is still the exception rather than the rule. For companies betting heavily on LLM tools, that leadership gap matters: if the people approving budgets do not fully grasp the downside scenarios, they are unlikely to invest in the slower, less glamorous work of making systems safe and dependable.

Why today’s LLM business tools are structurally fragile

When I put these threads together, Hinton’s skepticism about LLM‑centric business tools looks less like contrarianism and more like a diagnosis of structural fragility. Most corporate processes depend on traceability, version control and clear responsibility chains. Large language models, by contrast, are opaque, probabilistic and difficult to audit. If a customer‑service bot gives a refund that violates policy, or an internal assistant leaks confidential data in a generated email, it is rarely obvious why the model behaved that way or how to prevent a repeat. That opacity makes it hard to satisfy regulators, insurers and internal risk committees, no matter how impressive the demo.

There is also a cultural mismatch. Many LLM deployments are framed as magic productivity multipliers, dropped into existing workflows without rethinking incentives or accountability. Employees are told to “use the AI” but remain personally responsible for any mistakes, a setup that breeds quiet resistance and workarounds. Hinton’s broader criticism of tech giants for, in his view, ignoring systemic dangers while racing ahead with commercialization, captured in reports on his comments about tech giants, helps explain why so many of these tools feel bolted on rather than thoughtfully integrated. Until organizations design around the limitations of generative models instead of pretending those limitations do not exist, I expect a large share of LLM‑based business projects to keep failing quietly, regardless of how advanced the underlying models become.

More from Morning Overview