Artificial intelligence is quietly reshaping how rockets fly, how spacecraft sip propellant and how engineers think about the leap to nuclear propulsion. What began as a set of algorithms for optimizing trajectories is now starting to look like the missing software layer that could make high performance engines and even nuclear rockets practical beyond the lab. As AI systems learn to squeeze more thrust from every kilogram of fuel, the physics of deep space travel is beginning to tilt in favor of faster, more ambitious missions.

Instead of treating propulsion as a fixed piece of hardware, space agencies and startups are increasingly treating it as a dynamic system that can learn in flight. That shift, driven by machine learning and reinforcement learning, is already improving electric and chemical propulsion and is now being pulled into nuclear concepts that once lived only in science fiction. The result is a new race, not just to build better engines, but to pair them with smarter software that can safely push them to their limits.

AI turns propulsion into a learning problem

The most important change I see is conceptual: propulsion is no longer just a matter of valves, pumps and nozzles, it is a control problem that can be optimized in real time. Instead of precomputing a single “best” burn profile on the ground, engineers are training AI agents to adjust thrust, mixture ratios and pointing continuously as conditions change. That approach, rooted in reinforcement learning, treats every second of a mission as a chance to learn how to trade fuel, time and risk more efficiently.

Researchers working on what one report calls Dec, Could Revolutionize Space Travel, Faster Rockets and More Efficient Propulsion are already using AI-driven reinforcement learning to explore engine settings that human designers might never test, then locking in the most efficient patterns for use in flight, a strategy that could make nuclear powered rockets a reality. Similar reinforcement learning techniques are being tested on electric propulsion systems, where small, continuous adjustments to ion or Hall thrusters can add up to major gains over months-long missions. By framing propulsion as a learning problem, AI opens a path to engines that get better the longer they fly.

From bicycles to rockets, learning by experience scales up

What makes this shift plausible is that the same learning-by-doing logic that helps a child master a bicycle can be scaled up to orbital mechanics. In propulsion labs, AI agents are being trained in high fidelity simulators that model everything from combustion instabilities to solar radiation pressure, then rewarded when they find control strategies that deliver more delta-v for the same propellant. Once those agents are robust, they can be ported to onboard computers that keep refining their behavior as real sensor data flows in.

One recent analysis of how Dec is reshaping propulsion describes AI systems that start with conservative control laws, then gradually expand their operating envelope as they gain confidence, a pattern that could eventually extend to nuclear powered rockets as well. The same piece draws a straight line from everyday learning, like balancing on a bike, to machine learning systems that adjust thrust vectors and gimbal angles on the fly. By grounding exotic space hardware in familiar learning principles, engineers are making it easier to trust AI with decisions that used to be locked behind rigid flight software.

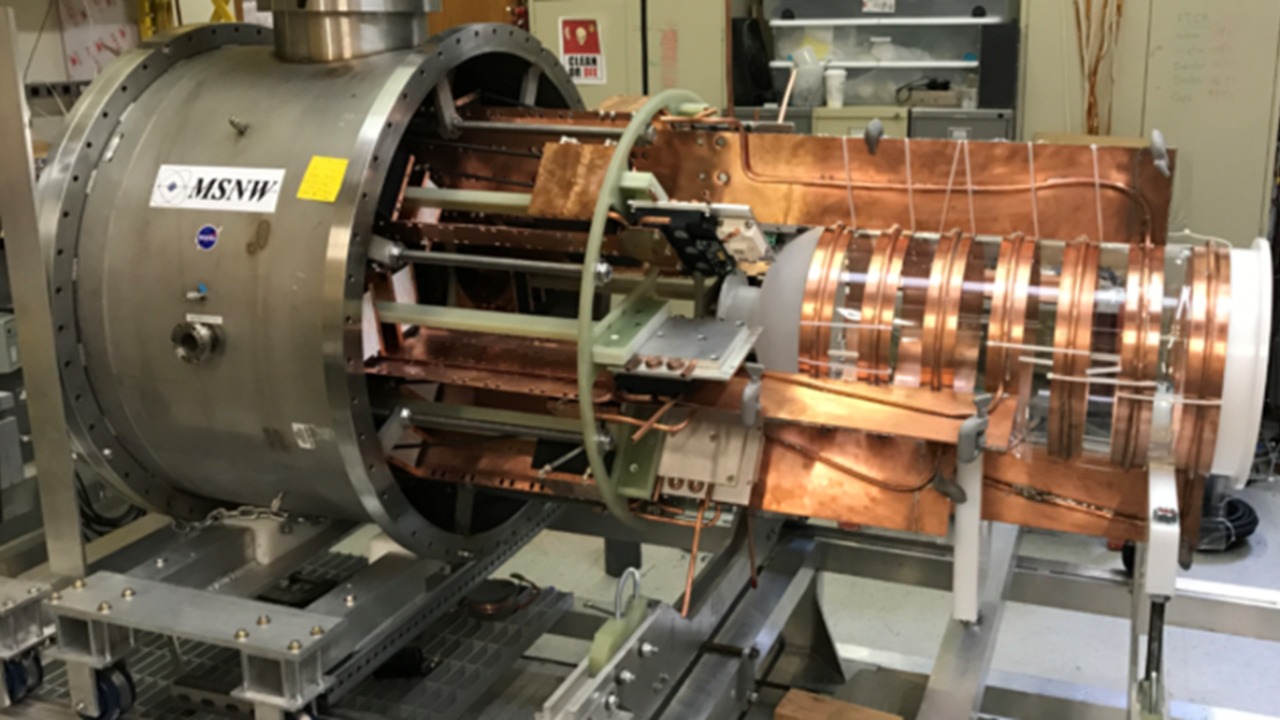

Inside the labs where AI is supercharging engines

In university and government labs, the work of turning those ideas into hardware is already under way. I see teams building digital twins of entire propulsion systems, from turbopumps to exhaust plumes, then letting AI agents experiment inside those virtual environments at machine speed. Every simulated failure, from a clogged injector to a thermal spike, becomes training data that helps the system recognize and avoid similar patterns in the real world.

One program described as using reinforcement learning for propulsion systems is pairing these digital twins with detailed models of nuclear fission, which works by splitting heavy atoms to release heat that can be transferred to propellant, and then asking AI to search for designs that maximize thrust without breaching safety margins, a process summarized in a UND overview that notes “Fission works by splitting heavy” nuclei and concludes, “Let’s begin with design” as the starting point for smarter engines. That same effort, detailed in a profile that invites readers with “Questions? Please contact Tom Dennis, UND associate director of communications, at [email protected], or Adam Kurtz,” shows how AI is being woven into every stage of propulsion development, from concept sketches to hot-fire tests, as described in how AI is supercharging spacecraft propulsion.

Why nuclear rockets are back on the table

As AI matures, it is colliding with a renewed push for nuclear propulsion that is driven by basic physics. Chemical rockets are limited by the energy stored in molecular bonds, which caps their exhaust velocity and forces mission planners to accept long transit times to Mars and beyond. Nuclear thermal propulsion, by contrast, uses a reactor to heat propellant to far higher temperatures, which can deliver much higher specific impulse and dramatically shorten travel times.

One detailed assessment notes that, essentially, for a given amount of propellant, a nuclear powered spacecraft could travel faster and sustain its thrust for longer, a capability that has drawn in major contractors such as Lockheed Martin and Blue Origin, as described in an analysis of why dreams of atomic rockets are back. That same report underscores that nuclear propulsion is not a speculative fantasy but a technology with clear performance advantages, provided engineers can manage reactor safety, radiation shielding and political concerns. AI does not change the underlying physics, but it does promise to manage the complexity of operating such systems in deep space.

NASA, DARPA and the nuclear demonstration push

The institutional momentum behind nuclear propulsion is no longer confined to white papers. NASA and DARPA are now targeting 2027 for an in space demonstration of nuclear thermal propulsion, a schedule that signals a serious commitment to flying hardware rather than just studying it. The planned demonstration aims to prove that a compact reactor can safely heat hydrogen propellant and deliver sustained thrust in orbit, a key step toward crewed missions that would benefit from shorter transit times and more flexible abort options.

In that context, AI is emerging as a potential force multiplier for both design and operations. The same machine learning tools that are reshaping propulsion design and operations in conventional engines are being evaluated for tasks like real time reactor monitoring, anomaly detection and adaptive thrust control in nuclear systems. A recent overview of interest in nuclear propulsion notes that NASA and DARPA see nuclear thermal propulsion as a cornerstone for deep space transportation, and AI is increasingly seen as the software layer that can keep such complex systems within safe operating bounds while still exploiting their performance.

Lessons from the nuclear energy industry’s AI experiments

One reason space engineers are confident about pairing AI with nuclear hardware is that the terrestrial nuclear energy industry is already doing it. Commercial reactors rely on extensive inspection and maintenance regimes, and a significant part of operation and maintenance requires staff to visually inspect equipment condition, a task that is now being augmented by computer vision and machine learning systems that can flag corrosion, cracks or misalignments more consistently than the human eye. Those same pattern recognition tools can be adapted to monitor spaceborne reactors, where access is limited and every anomaly matters.

An industry report notes that AI and ML are not intended to replace human oversight but to enhance it, with the International Atomic Energy Agency emphasizing that these tools still require careful human interaction, a point captured in an assessment of how the nuclear energy industry could benefit from AI. For space, that philosophy translates into AI systems that watch for subtle shifts in reactor temperature, neutron flux or coolant flow, then alert ground controllers or onboard autonomy when something drifts out of family. The goal is not to hand the keys to an algorithm, but to give human operators a richer, faster picture of what is happening inside a nuclear rocket.

Small satellites, smarter propulsion and the AI testbed

While nuclear propulsion grabs headlines, the proving ground for AI in space is often much smaller. The small satellite revolution is reshaping the space industry by enabling a more diverse range of missions, fostering constellations that can provide global coverage and opening access to organizations that once could not afford to fly. These compact platforms are ideal testbeds for AI driven propulsion control, because they can tolerate more experimental software and can be launched in large numbers, allowing rapid iteration.

One overview of how technology is revolutionizing space travel notes that the small satellite revolution is reshaping the space industry by enabling a more diverse range of missions, fostering new business models and extending coverage into regions where human presence is challenging or dangerous, a trend that is particularly visible in Earth observation and communications constellations described in how technology is revolutionizing space travel. On these platforms, AI can manage tiny electric thrusters that maintain formation, dodge debris or adjust orbits to improve coverage, all while learning from the collective behavior of the constellation. The same algorithms, once proven, can be scaled up to larger spacecraft and eventually to nuclear stages.

Engineers and students are already betting on AI propulsion

Behind the scenes, a new generation of engineers and graduate students is building its careers around the intersection of AI and propulsion. Many of them are less interested in debating whether AI belongs in critical systems and more focused on how to validate and certify it. They are developing test frameworks that bombard AI controllers with edge cases, from sensor dropouts to off nominal thrust, to ensure that the system fails gracefully rather than catastrophically when reality diverges from the training data.

In one public discussion, a team described itself as a group of engineers and graduate students who are studying how AI in general, and a subset of AI called machine learning, is reshaping propulsion design and operations, a perspective captured in a report that asks whether AI can transform space propulsion. Their work spans everything from optimizing nozzle shapes to designing controllers that can switch between different propulsion modes mid mission. By embedding AI literacy into propulsion engineering education, they are ensuring that future nuclear rocket projects will have teams fluent in both reactor physics and machine learning.

The real reason nuclear rockets need AI

When I look at the arguments for nuclear rockets, the most compelling are not about prestige or nostalgia, but about mission architecture. Nuclear thermal propulsion promises to cut travel times to Mars, which reduces radiation exposure for crews and opens up launch windows that are less constrained by planetary alignment. It also offers higher thrust than electric propulsion, which is crucial for heavy payloads and rapid abort options. Those advantages, however, come with a control problem that is far more complex than lighting a chemical engine for a few minutes at a time.

A detailed explainer on the real reason NASA is developing a nuclear rocket walks through the technological hurdles that separate current space exploration capabilities from the demands of deep space missions, highlighting the need for propulsion systems that can operate efficiently over long durations while managing reactor dynamics, a challenge illustrated in a video on the real reason NASA is developing a nuclear rocket. AI is well suited to that challenge because it can monitor thousands of parameters simultaneously, learn normal operating patterns and flag deviations before they escalate. In practice, that could mean AI assisted controllers that adjust control drums in a reactor, tweak propellant flow or reorient radiators to keep temperatures within safe bands, all while optimizing thrust for the mission profile.

From concept to reality: how fast can AI nuclear propulsion arrive?

The timeline for AI enabled nuclear propulsion will depend less on algorithms and more on politics, regulation and testing infrastructure. The software pieces, from reinforcement learning controllers to anomaly detection systems, are already being demonstrated on conventional engines and small satellites. The harder part is integrating them into nuclear hardware that must satisfy both spaceflight reliability standards and nuclear safety rules that were written long before AI entered the picture.

Still, the convergence is accelerating. Reports that describe Dec, Could Revolutionize Space Travel, Faster Rockets and More Efficient Propulsion, alongside renewed interest in nuclear systems from NASA, DARPA, Lockheed Martin and Blue Origin, suggest that the community is moving from speculative studies to concrete roadmaps that treat AI as a core enabler rather than an optional add on. If the 2027 nuclear thermal demonstration proceeds on schedule and if AI continues to prove itself on smaller propulsion systems, the first generation of AI assisted nuclear stages could be flying within the next decade, not as science fiction props but as workhorse engines for deep space exploration.

More from MorningOverview