When two black holes slam together, they do not simply vanish into darkness, they ring like struck bells and briefly light up the universe in ripples of gravity. For the first time, a handful of exquisitely measured collisions are turning those ripples into a laboratory, revealing how black holes really behave when pushed to their limits. I want to walk through how a single cosmic crash, backed by a growing cast of extreme mergers, is transforming black holes from theoretical curiosities into precisely tested objects of physics.

The merger that turned spacetime into a laboratory

The turning point came when a team led by Dec and Isi realized that a black hole collision could be treated less like a distant catastrophe and more like a controlled experiment. Instead of focusing only on the initial burst of gravitational waves as two black holes spiraled together, they dug into the fading “ringdown” signal, the subtle oscillations that echo as the merged object settles into a final, stable state. That ringdown, they argued, should carry a fingerprint of the new black hole’s mass and spin, and if general relativity is right, every part of the signal must tell a consistent story about that final object.

To test that idea, Dec and Isi turned to data from LIGO, which had captured the gravitational waves from a powerful merger in 2021. By isolating multiple tones in the ringdown, they could compare the properties implied by each oscillation and check whether they all matched a single, well behaved black hole. The result was a remarkably clean confirmation that the merged object behaved exactly as Einstein’s equations predict, with no sign of exotic structure or hidden hair lurking beneath the event horizon.

How ringdown “tones” expose a black hole’s true nature

What makes this approach so powerful is that it treats the final black hole like a musical instrument, one that can only play certain allowed notes. In Einstein’s theory, a black hole is fully described by just a few numbers, such as its mass and spin, and those numbers determine the precise frequencies at which it can ring. If observers can measure more than one of those frequencies, they can cross check whether they all correspond to the same simple object or whether something more complicated is hiding in the data.

Advances in detector sensitivity have finally made that kind of “black hole spectroscopy” possible. The same collision that Dec and Isi analyzed produced a ringdown strong enough that multiple tones could be teased out of the noise, a feat that earlier generations of instruments could not achieve. Those improvements in detector sensitivity turned what used to be a single, blurry chirp into a structured signal that can be dissected, compared, and used to test whether the final black hole really matches the clean, featureless object predicted by relativity.

Einstein and Hawking meet the data

For decades, the behavior of black holes lived mostly on chalkboards and in computer simulations, where Albert Einstein’s equations and Stephen Hawking’s ideas about horizons and radiation could be explored in thought experiments. The new generation of gravitational wave detections is finally putting those ideas in direct contact with reality. When Astronomers captured a collision between two black holes in unprecedented detail, they were not just adding another event to a catalog, they were checking whether the merged object obeyed the strict rules that Einstein and Hawking laid down.

The detailed waveform from that event showed a system that matched the predictions of general relativity at every stage, from the inspiral to the final ringdown. The mass and spin of the remnant, inferred from the gravitational waves, lined up with the expectations for a classical black hole that has swallowed its partners and settled into a stable configuration. In particular, the observed signal confirmed decades old predictions by Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking about how horizons should behave when black holes merge, with no evidence that information leaks out or that the horizon does anything other than grow as the system evolves.

The “impossible” collision that stressed relativity

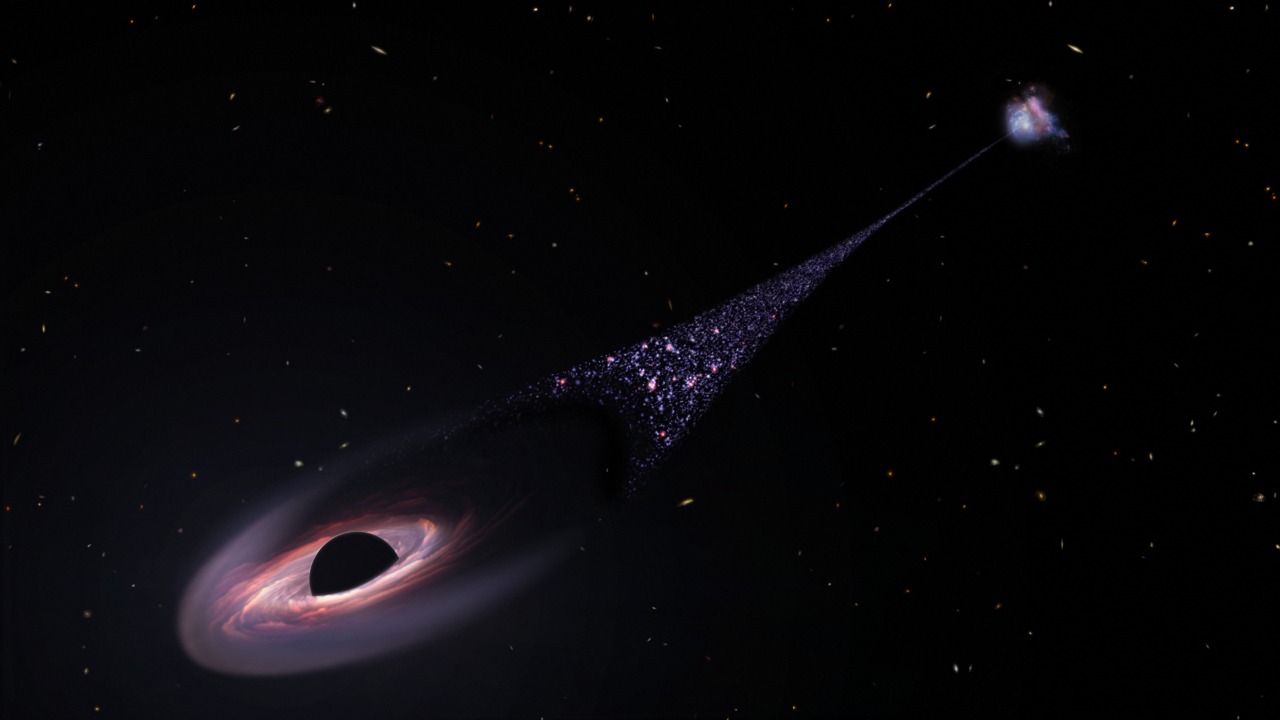

Even as some mergers quietly confirm the standard picture, others have looked, at first glance, like they should not exist at all. One record breaking event involved black holes so massive and so oddly paired that it was initially labeled an Impossible collision, a system that seemed to push relativity to its breaking point. The masses of the components appeared to fall into a range where stellar evolution models say black holes should be rare or absent, raising the possibility that something more exotic was going on.

As researchers dug deeper into the data from the merger event known as GW231123, they found that the waveform still fit within Einstein’s framework, but only after they accounted for more complex astrophysical histories. The Impossible pairing could be explained if earlier generations of black holes had already merged and then collided again, building up heavier objects in dense stellar environments. In other words, the event did not overthrow relativity, it forced theorists to refine their understanding of how black holes grow and cluster, and it showed that even extreme systems like GW231123 still behave like ordinary black holes once they collide.

The loudest signal and what it says about spacetime

Some collisions stand out not because they are forbidden on paper, but because they are simply enormous. In one case, Two massive black holes crashed into each other 1.3 billion years ago, sending out a gravitational wave signal so strong that it has been described as the loudest space signal ever recorded. The energy released in that instant dwarfed anything humans can produce, briefly outshining entire galaxies in gravitational radiation.

What makes that event scientifically valuable is not just its drama, but its precision. The ripples that reached detectors in PASADENA, Calif, stretched and squeezed spacetime on Earth by less than the width of a proton, yet they carried a clear record of the masses, spins, and final state of the system. By matching that record to theoretical templates, researchers could confirm that the merged object behaved like a textbook black hole, with a smooth horizon and no sign of extra structure. The fact that such a violent, distant event could be reconstructed from such tiny distortions, as reported in the analysis of the loudest space signal ever, underscores how sensitive our instruments have become and how cleanly black holes broadcast their properties when they collide.

Two unique mergers and a growing black hole census

Individual showpiece events grab headlines, but the real transformation in our understanding comes from building a population of well measured collisions. Earlier this year, The LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA, Collaboration reported Key Takeaways from two unique black hole merger events, labeled GW241011 and GW241110, that expanded the known diversity of these systems. One featured a black hole with an unusually high spin, while the other involved a mass ratio that challenged simple formation scenarios, hinting at complex dynamical interactions in star clusters or galactic nuclei.

By comparing these two mergers to the broader catalog, researchers can start to see patterns in how black holes pair up, how fast they typically spin, and how often they collide more than once. The fact that the same network of detectors could capture both a nearly equal mass system and a highly asymmetric one, as described in the report on two unique black hole mergers, shows that nature is exploring a wide range of possibilities. Each new point in that distribution helps refine models of stellar evolution and cluster dynamics, and it tests whether the final merged objects always land on the same simple curve of mass and spin predicted by general relativity.

What “no hair” really means when black holes collide

At the heart of these observations is a deceptively simple claim known as the “no hair” theorem, the idea that black holes, once formed, forget almost everything about the matter that created them. In practice, that means two very different formation histories can lead to the same final object, as long as the mass and spin match. Collisions provide a rare chance to test this principle, because they let us watch black holes with known properties combine and then check whether the remnant is fully described by just a few numbers.

The ringdown analyses by Dec and Isi, the detailed waveform studied by Astronomers, and the extreme cases like the Impossible GW231123 event all point in the same direction. In every case where the data are strong enough to probe the final state, the merged object behaves like a clean, featureless black hole, with no extra “hair” in the form of additional multipole moments or long lived oscillations that would betray new physics. That consistency does not rule out all exotic possibilities, but it sharply limits how much room there is for alternatives, and it shows that, at least in the violent regime of mergers, black holes really do act like the simple solutions of Einstein’s equations.

How detectors turned from proof of concept to precision tools

None of this would be possible without a quiet revolution in the hardware that listens for gravitational waves. The first detections were triumphs of engineering, but they were barely strong enough to confirm that black holes collide at all. Since then, upgrades to LIGO and its partner observatories have steadily pushed down the noise, allowing them to pick out weaker signals, resolve finer details in the waveforms, and capture events from farther across the universe.

Those improvements are not just incremental, they change the kind of science that can be done. With higher sensitivity, detectors can isolate multiple ringdown tones, distinguish between different spin configurations, and measure subtle effects like precession and orbital eccentricity. The analysis of the 2021 collision by Dec and Isi, enabled by the enhanced capabilities of LIGO, is a clear example of how an instrument that once only heard a single chirp can now perform spectroscopy on the final black hole. As future upgrades come online, the same facilities will be able to test even more subtle deviations from general relativity, or confirm its predictions with unprecedented precision.

Why these collisions matter beyond black hole physics

It is tempting to treat black hole mergers as a niche corner of astrophysics, but the stakes reach far beyond the behavior of horizons. Each collision is a probe of gravity in its strongest regime, a place where any cracks in Einstein’s theory are most likely to show up. So far, even the most extreme events, from the loudest signal produced when Two massive black holes collided 1.3 billion years ago to the Impossible GW231123 system, have fallen in line with general relativity, tightening the constraints on alternative theories that try to modify gravity at large scales.

At the same time, the growing catalog of mergers is reshaping how I think about the life cycles of stars and galaxies. The unique events highlighted by The LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA, Collaboration show that black holes can grow through repeated mergers, spin up or slow down depending on how they pair, and cluster in environments that encourage complex interactions. Those details feed back into models of galaxy evolution, the rate at which heavy elements are produced, and even the background hum of gravitational waves that future detectors will try to map. In that sense, every new collision is not just a test of how black holes behave, it is a data point in a much larger story about how the universe builds structure from the remnants of dead stars.

More from MorningOverview