Archaeologists in southern Turkey have uncovered a 3,500-year-old clay tablet that reads less like royal propaganda and more like a household errand. Inscribed in cuneiform, the tiny slab records a bulk order of wooden furniture, a reminder that even in the Late Bronze Age, people were tracking what they bought and from whom. I see in this ancient list not just a curiosity from the past, but an early snapshot of consumer life that looks surprisingly familiar to anyone who has ever scrolled through an online cart.

What people really bought, it turns out, were the same kinds of practical, status-laden goods that still anchor modern homes, and they relied on written records to manage those transactions. The tablet captures a moment when accounting, shopping and everyday logistics were already sophisticated, and it invites a closer look at how a simple list can illuminate the economy, technology and social habits of a world that vanished three and a half millennia ago.

Unearthing a shopping list in the ruins of an ancient city

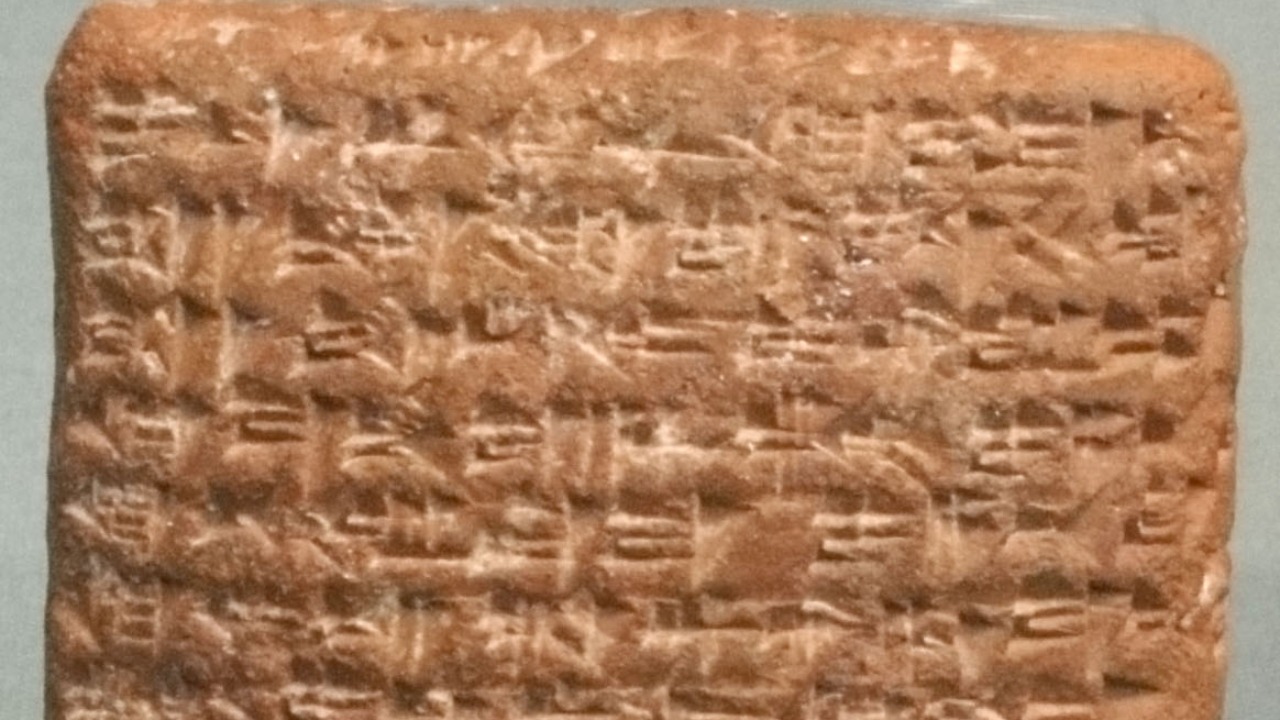

The story begins in the ruins of Aççana Höyük in southern Turkey, where an excavation team uncovered a small clay tablet that initially looked like countless other administrative fragments. Only when specialists cleaned and read the cuneiform did they realize it was not a royal decree or a diplomatic letter, but a detailed record of a large furniture purchase. The tablet, written in the Late Bronze Age, lists wooden items ordered from a supplier, turning a routine transaction into a rare window on daily economic life in the ancient Middle East.

Experts who examined the find have described it as a kind of receipt, documenting a delivery of wooden furniture from an unnamed seller to a buyer whose identity is also lost. The text, written in the script used across the region, shows that people in Turkey were already using written records to track purchases and obligations in a way that feels strikingly modern. The excavation team in Turkey and the Experts who translated the tablet have emphasized that this is not a royal inscription but a practical document, a reminder that writing in the ancient Middle East was as much about managing goods as glorifying kings.

What the list actually says people bought

At the heart of the tablet is a straightforward message: someone in this ancient city wanted furniture, and they wanted a lot of it. The text itemizes wooden pieces, likely including chairs, tables or storage chests, ordered in quantity from a single supplier. While the exact vocabulary is technical and tied to Late Bronze Age terminology, the structure is familiar, with a list of items, quantities and a clear indication that this was a commercial transaction rather than a gift or tribute. In other words, it is a shopping list that doubles as a record of what was owed and what was delivered.

The details matter because they show that the buyer was not picking up a single stool or a casual trinket, but commissioning a substantial set of furnishings, probably for a household or institutional space. The tablet describes a purchase of wooden furniture from an unknown seller, a fact that has been highlighted in modern discussions of the find as an early example of a written receipt. One analysis of retail history even points to this clay document from Turkey as the earliest known example in a long tradition of Paper receipts, noting that it records a 3,500-ye old transaction for wooden furniture from an unknown seller.

From clay to cuneiform, how a receipt was made

To understand why this list survived, it helps to picture how it was created. A scribe would have taken a small lump of wet clay, shaped it into a tablet and then pressed a reed stylus into the surface to form cuneiform wedges. Each sign encoded syllables or words in the language of the region, and the scribe followed a standard layout to record the items, quantities and parties involved. Once the text was complete, the tablet was dried, either in the sun or in a kiln, turning a fleeting transaction into a durable artifact that could be stored, checked and, as it happens, rediscovered thousands of years later.

The tablet from Aççana Höyük is part of a broader tradition of cuneiform record keeping that stretched across Mesopotamia and Anatolia. Archaeologists have described it as a 3,500-Year-Old Old Cuneiform Tablet Found Containing a Shopping List in Turkey, emphasizing that it was created by Archaeologists excavating the site and that it preserves a text once spoken in the languages of ancient Mesopotamia. The survival of such a fragile object is partly an accident of history, but it also reflects a deliberate choice by ancient administrators to fix their economic dealings in clay, a medium that outlasted the palaces and storerooms where it was first filed.

A 3.500-year-old accountant at work

Behind the neat rows of cuneiform signs is a person whose job would be instantly recognizable to any modern bookkeeper. In the 15th century BCE, someone trained in the scribal tradition sat down to record this order, acting as an ancient accountant who translated a spoken agreement into a permanent ledger entry. The tablet captures their work at a moment when literacy was specialized, and the ability to write such a list signaled both education and a role within the administrative machinery of the city.

One modern account of the discovery describes how, in the 15th century BCE, an ancient accountant recorded a 3.500-year-old list of Shopping items on a Clay Tablet in Turkey, preserving the details of the transaction for posterity. That description, drawn from a report on a Clay Tablet found in Turkey that reveals a 3.500-year-old Shopping list, underscores how routine this work would have been at the time. In the context of a palace or large household, the scribe was not writing literature or law, but keeping track of furniture, wood and obligations, a reminder that much of the earliest writing is, at its core, about getting the numbers right.

Shopping, status and everyday life in Late Bronze Age Turkey

What people bought tells us as much about their aspirations as their needs. A bulk order of wooden furniture in a Late Bronze Age city suggests a household or institution that wanted to furnish rooms with durable, possibly ornate pieces. Wood was a valuable resource, especially in regions where high quality timber had to be imported, so a list like this hints at wealth and social standing. The buyer was not scraping together a single stool, but commissioning a coordinated set, perhaps for a new residence, a guest hall or an administrative office.

The fact that the transaction was recorded in writing also points to a culture in which goods, credit and obligations were carefully tracked. In Turkey at this time, cities like Aççana Höyük sat at crossroads of trade routes that linked Anatolia, Syria and Mesopotamia, and written lists helped manage the flow of commodities through these networks. Modern summaries of the find note that the tablet from Turkey records a substantial order of furniture, and that it fits into a broader pattern of Late Bronze Age Shopping and accounting practices. One report on a 3,500-year-old shopping list found on a cuneiform tablet highlights how such records help preserve the cultural heritage of Anatolia for future generations, because they show not just what elites built, but how ordinary spaces were furnished and used.

How this list fits into the long history of receipts

Although the tablet feels unique, it belongs to a much older story about how humans learned to track transactions. Long before anyone pressed a stylus into clay, people in Western Asia used tokens and tallies to represent quantities of grain, livestock or goods. These physical counters, sometimes sealed in clay envelopes, allowed communities to record obligations and payments even before writing systems existed. Over time, the marks on clay evolved into full scripts, and the same impulse to document who owed what turned into written contracts, inventories and, eventually, shopping lists.

Research on ancient finance practices notes that the earliest transaction records pre date writing systems and go as far back as an estimated 8000 BCE, when tokens and other devices were used across ancient Western Asia for millennia to track exchanges. A detailed discussion from a modern scholar explains how these early systems of counting and recording laid the groundwork for later cuneiform tablets that combined words and numbers in a single document. In that context, the furniture list from Aççana Höyük is not an isolated curiosity but part of a continuum that stretches from Neolithic tokens to the clay tablets described by BCE era finance experts, and eventually to the digital receipts that now land in our email inboxes.

Public fascination, jokes and the Reddit test

When news of the tablet reached the wider public, the reaction was a mix of fascination and humor. On social platforms, people seized on the idea that someone 3,500 years ago was essentially doing what modern shoppers do every weekend, compiling a list of things to buy and making sure the seller delivered. The notion that an ancient person had left behind what looks like a mundane errand list made the past feel less remote, and it sparked a wave of comments about how little human habits have changed.

One discussion thread captured this blend of curiosity and playful disappointment. A user named Jul shared the story under the title about a 3,500-year-old tablet in Turkey turning out to be a shopping list, prompting another commenter to write, “I feel cheated,” because They were hoping for more dramatic contents. Others noted that They aren’t very specific but do mention what items were listed, focusing on the furniture and the practical nature of the text. That exchange, preserved in a Reddit history forum, shows how even a dry administrative tablet can become a cultural touchpoint, inviting people to project their own expectations and sense of humor onto the ancient record.

From clay tablets to digital receipts, what has really changed?

Seen against the sweep of history, the furniture list from Aççana Höyük is an ancestor of every receipt that has ever crumpled in a wallet or vanished in an email archive. The basic functions are the same: to document a transaction, to provide proof of purchase and to create a record that can be checked if something goes wrong. What has changed is the medium, from clay to papyrus, parchment, paper and now pixels, and the speed with which those records are created and shared. Yet the impulse behind them, the desire to fix a moment of exchange in a durable form, remains constant.

Modern retail analysts point out that paper receipts have been around for thousands of years, and that the earliest known example was discovered in Turkey, a 3,500-ye old record of wooden furniture from an unknown seller that functions much like a modern proof of purchase. Today, as retailers debate the death of the paper receipt and what they need to do next in an era of contactless payments and app based loyalty programs, the clay tablet from Turkey offers a reminder that every technological shift in record keeping builds on a very old habit. The move from clay to digital does not erase the continuity between a Late Bronze Age shopping list and the line items that appear on a smartphone screen after a furniture order from a global brand.

Why a 3,500-year-old list still matters

It might be tempting to dismiss a list of furniture as a minor curiosity compared with grand inscriptions or spectacular treasures, but that would miss its real value. Documents like this tablet illuminate the infrastructure of everyday life, the systems of credit, delivery and accountability that made ancient cities function. They show that people in the Late Bronze Age cared about the same things modern consumers do, from the reliability of suppliers to the need for clear records when money and goods change hands. In that sense, the tablet is not just about what people bought, but about how they organized their economic world.

Officials in Turkey have emphasized that finds like this are crucial for understanding and preserving the region’s heritage. In a recent statement, Mehmet Ersoy, the Minister of Culture and Tourism, highlighted how archaeologists working in Jul have unearthed a 3,500-year-old shopping list that helps document the daily life of Anatolia and supports efforts to protect its cultural legacy for future generations. That perspective, reflected in reports on the Minister of Culture and Tourism and his comments, underscores why a single clay tablet can command global attention. It is not only a relic of a transaction, but a rare, tangible link between the shopping habits of the past and the consumer routines that still shape our lives today.

More from MorningOverview