Scientists working on nuclear fusion say they have crossed a crucial threshold on the path to harnessing the same kind of power that lights the sun, describing their latest results as a foundation for turning experimental machines into practical energy sources. The new work does not mean fusion electricity is ready for the grid, but it signals that the physics and engineering are starting to line up in ways that were elusive for decades. I see this moment less as a single breakthrough and more as a coordinated shift, where laboratory results, private investment and government strategy are finally pointing in the same direction.

From starfire to power plant: what “sun-level” really means

When researchers talk about matching the power of the sun, they are not promising a miniature star in every suburb, they are trying to reproduce the fusion reactions that let light nuclei merge into heavier ones and release energy. In the sun, gravity provides the crushing pressure that forces hydrogen atoms together, but on Earth, scientists have to use intense magnetic fields or powerful lasers to create the extreme conditions that allow nuclei to overcome their natural repulsion and fuse into a new nucleus. That is the core challenge behind every fusion experiment, whether it uses a doughnut-shaped tokamak, a compact spherical device or a bank of high energy lasers.

Recent reporting describes how Scientists are focusing on the precise moment when two light nuclei collide hard enough to create a new nucleus and release energy, the same basic process that powers the sun. In the latest experiments, teams have pushed their machines closer to the conditions where fusion reactions can sustain themselves, a regime where the plasma is hot and dense enough that each reaction triggers more reactions in a chain. That is what makes this step feel like a bridge between pure physics and the blueprint of a future power plant.

The new experiment that “laid the foundation”

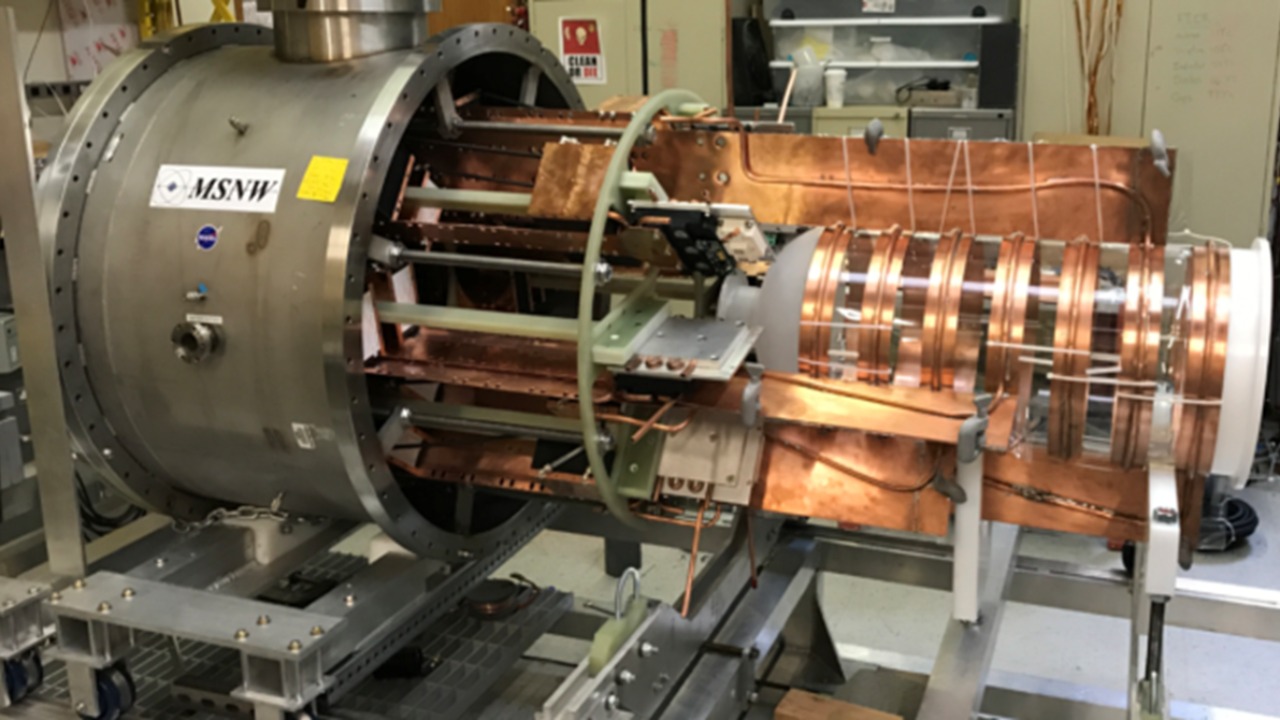

The most recent advance centers on a set of experiments that researchers describe as a major step toward a nearly limitless power source, because the results show that today’s experimental machines can be tuned to behave more like tomorrow’s reactors. In these tests, scientists managed to keep a superheated plasma stable long enough, and under tight enough control, to study how energy flows through it and how fusion reactions might be amplified rather than quenched. The phrase “this will lay the foundation” is not casual optimism, it reflects a belief that the data from these runs can be used to design devices that are smaller, more efficient and easier to maintain than the giant machines of the past.

According to one detailed account, Scientists are taking a step toward developing a nearly limitless power source by refining how they handle the extreme conditions created by plasma inside their reactors. As Interesting Engineering explained in that coverage, the team’s work shows how careful control of temperature, density and magnetic confinement can push a machine closer to the point where fusion power outpaces the energy needed to run the device. I read that as a sign that the community is moving from proof of principle shots toward repeatable operating regimes that engineers can actually design around.

Tokamak Energy and the race to commercial reactors

One of the clearest examples of this shift from experiment to application comes from Tokamak Energy, a U.K. company that has staked its future on compact spherical reactors. The company recently announced what it called another nuclear fusion energy breakthrough, reporting that its latest device achieved performance levels that support its roadmap toward grid connected systems. For a long time, tokamaks were seen as massive national projects, but Tokamak Energy is trying to prove that smaller, privately funded machines can reach the same physics milestones faster and at lower cost.

In a recent report, Tokamak Energy was credited with making progress toward energy producing fusion systems, with Interesting Engineering highlighting how its technology could feed into future commercial plants. The company’s work fits into a broader pattern in which private firms are no longer just following government labs, they are setting their own performance targets and timelines. I see that as a healthy tension, because it forces the field to balance scientific caution with the urgency of building real hardware that can survive in industrial settings.

Major Breakthrough and the global fusion landscape

The latest experiments are not happening in isolation, they sit on top of a wave of progress that some analysts have described as a Major Breakthrough in Nuclear Fusion. Earlier this month, researchers reported that they had pushed the boundaries of fusion performance further than ever before, both in terms of the energy produced and the stability of the plasma. That kind of language is not used lightly in a field that has been burned by hype, and it reflects a consensus that the physics barriers that once seemed insurmountable are starting to give way.

One detailed briefing on this progress framed it as Advancements Promise a Sustainable Energy Future, emphasizing that the latest results push the boundaries of Nuclear Fusion research further than ever before. The same analysis stressed that this is not just about one lab or one country, it is about a global ecosystem of projects that are learning from each other and iterating faster than in previous decades. When I look across those efforts, I see a field that is finally starting to behave like a modern technology sector rather than a collection of isolated physics experiments.

Materials, magnets and the quiet revolution in hardware

Behind the headlines about record plasmas and new performance milestones lies a quieter revolution in the materials and magnets that make fusion possible. The superheated plasma at the heart of a reactor can reach temperatures hotter than the sun, and any wall or component that touches it has to survive intense heat, radiation and mechanical stress. That is why so much attention is now focused on advanced alloys, ceramic composites and novel cooling systems that can keep a reactor running for months or years instead of seconds.

The United States Department of Energy is playing a central role in this hardware push, with the DOE investing in the development of advanced materials that can withstand the extreme conditions inside fusion devices. That same program is also backing new generations of high field magnets that can generate the magnetic fields needed to contain the plasma in a compact volume. I see these investments as the nuts and bolts of the fusion story, because without materials that can survive and magnets that can be manufactured at scale, even the most elegant plasma physics will never leave the lab.

Trump Media, TAE and the politics of fusion funding

Fusion’s shift from laboratory curiosity to potential power source is also reshaping the politics and financing around the technology. One of the most striking recent moves is a deal in which Trump Media and Technology Group agreed to Merge with TAE Technologies, a long standing fusion power company that has been developing its own reactor concepts. The merger signals that fusion is no longer just a niche interest for energy specialists, it is becoming a strategic asset that media and technology investors want to align with.

On its own site, TAE highlighted this as part of its Latest news, presenting the combination with Trump Media and Technology Group as a way to accelerate the development of a Future Power Plant based on its Technologies. A separate report, written By Timothy Gardner for Reuters, noted that President Donald Trump appeared at the Winning the AI Race Summit while the deal was being discussed, underscoring how fusion is now intertwined with broader debates over innovation and national competitiveness. I read this merger as a sign that fusion companies are looking for unconventional partners and capital sources to bridge the long, expensive gap between prototypes and commercial plants.

Government timelines and Energy Secretary Chris Wright’s bet

While private investors are making bold moves, governments are still central to fusion’s trajectory, both as funders and as regulators. In the United States, Energy Secretary Chris Wright has been unusually explicit about his expectations, telling an interviewer that he believes fusion could start to power the world within a specific time window. That kind of statement matters because it shapes how agencies allocate research budgets and how utilities think about long term planning for their grids.

In a recent conversation captured by BBC cameras, US Energy Secretary Chris Wright spoke to Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, with images credited to Pol Reygaerts, and suggested that fusion could start contributing to global energy supplies in eight to 15 years. That is an aggressive timeline, but it aligns with the pace of progress in experiments and the surge of private sector activity. I see his comments as both a vote of confidence and a challenge, because they set expectations that researchers and companies will now be judged against.

Why this step matters for climate and energy security

The reason this latest foundation laying step in fusion matters so much is that it arrives at a moment of intense pressure on the world’s energy systems. As countries try to cut carbon emissions while keeping electricity reliable and affordable, they are running into the limits of existing technologies, from the variability of wind and solar to the political resistance around new fission reactors. Fusion offers a different path, one that promises high power density, minimal long lived waste and fuel sources that are widely available.

Analysts who framed the recent progress as a Sustainable Energy Future emphasized that fusion could eventually provide a long term power source that does not depend on weather or imported fuels. When I connect that vision to the concrete steps described by Dec and other recent reports, from improved plasma control to new materials and corporate mergers, I see a field that is finally aligning its scientific ambitions with the practical demands of the energy transition. The sun is still a long way from our sockets, but the path between them has never looked clearer.

The next hurdles after the “foundation” is laid

For all the excitement around this latest milestone, the hardest work may still lie ahead. Turning experimental shots into a working power plant will require solving problems that go far beyond achieving fusion conditions, including how to extract heat efficiently, convert it to electricity, maintain components in a harsh environment and meet regulatory standards. There is also the question of cost, because fusion will have to compete with rapidly falling prices for renewables, batteries and advanced fission reactors.

Some of the most detailed accounts of the recent experiments, including those that mention Dec and even interface elements like Click prompts, stress that the current results are still in the realm of research rather than commercial deployment. They describe how teams are using today’s experimental machines as testbeds to understand how plasmas behave and how materials respond, with the explicit goal of informing the design of future reactors. I take that as a reminder that while the foundation may be laid, the building itself will require years of engineering, policy work and public engagement to rise to its full height.

More from MorningOverview