Engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have designed a new aluminum alloy that can be 3D printed and reach roughly five times the strength of standard cast aluminum used in everyday components. By pairing advanced metallurgy with machine learning, they have turned a notoriously tricky metal into a platform for lightweight parts that behave more like high‑end aerospace materials than the soft metal in a soda can.

The result is not just a stronger alloy, but a blueprint for how data‑driven design can unlock new performance in familiar elements, from aluminum to rare‑earth blends. If it scales, this approach could reshape how industries from aviation to electric vehicles think about structural parts, weight, and cost.

How MIT’s printable aluminum breaks the strength barrier

The core achievement is straightforward to state and difficult to overstate: MIT engineers have created a printable aluminum that can reach about five times the strength of conventional cast alloys while still being processed in a 3D printer. Traditional aluminum parts, such as those made from common casting grades, are limited by microstructures that form as the metal cools, which cap their strength and make them prone to cracking under the intense thermal cycles of additive manufacturing. By contrast, the new alloy is engineered so that its internal structure remains stable during printing, allowing it to carry far higher loads without sacrificing the low density that makes aluminum attractive in the first place.

To get there, the team applied machine learning techniques to sift through vast combinations of alloying elements and processing conditions, searching for recipes that would resist the cracking and weakness that plague standard aluminum powders. Instead of relying solely on trial‑and‑error experiments, they used algorithms to predict which compositions would form the right phases during solidification, then validated those predictions in the lab to arrive at a 3D‑printable aluminum alloy that can be produced on existing metal printers and still deliver the fivefold strength increase over conventional alloys, as detailed in their description of printable aluminum five times stronger than conventional alloys.

Machine learning as a new kind of foundry

What makes this project stand out is not only the final material, but the way it was discovered. Instead of starting with a handful of candidate alloys and slowly tweaking them, the researchers treated alloy design as a data problem, feeding models with information about how different elements interact and how microstructures evolve during rapid solidification. The algorithms then highlighted promising combinations that human intuition might have skipped, effectively turning the computer into a new kind of foundry where potential materials are cast in silico before any metal is melted.

This digital‑first strategy is already being recognized as a template for future work in structural metals. In coverage of the project, the team is described as using machine learning to guide the development of a “printable” aluminum that can survive the extreme thermal gradients inside laser powder bed systems and other additive platforms, a capability that has been singled out in a Tech Briefs media description of MIT researchers who are pushing 3D‑printed metals toward applications as demanding as jet engines. In that sense, the alloy is both a product and a proof of concept for AI‑assisted metallurgy.

From lab alloy to additive manufacturing workhorse

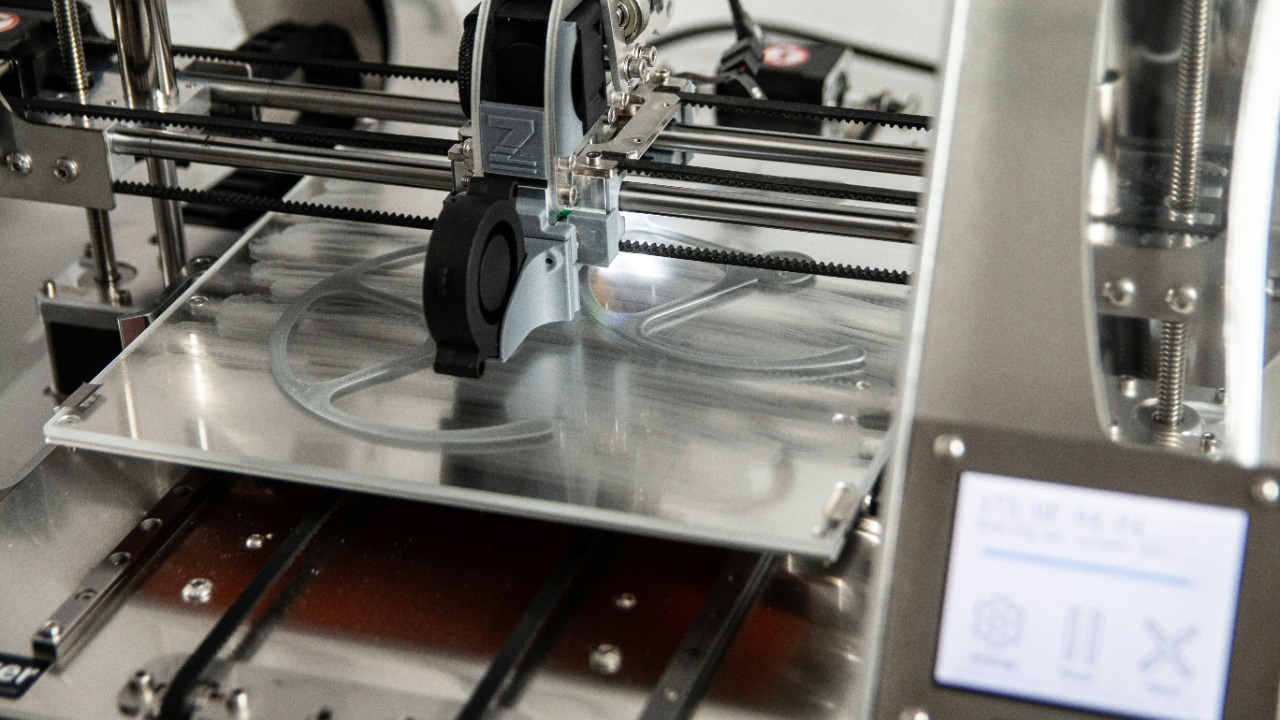

Turning a high‑performance alloy into a practical industrial material requires more than a strong tensile test. It has to be compatible with real additive manufacturing workflows, from powder production to part finishing, and it has to behave predictably across different machines and build geometries. Engineers at MIT have framed their new aluminum specifically for Additive Manufacturing, focusing on compositions and process windows that fit within the constraints of commercial printers rather than exotic, one‑off lab setups. That choice signals an intent to move quickly from research samples to parts that can be qualified for use in vehicles, aircraft, and energy systems.

Reports on the project emphasize that engineers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology designed the alloy with additive processes in mind, highlighting that MIT develops 5x stronger aluminium alloy for Additive Manufacturing by tailoring its chemistry and microstructure to withstand the repeated melting and solidification cycles of layer‑by‑layer fabrication. By aligning the material’s behavior with the realities of powder‑based production, the team has positioned the alloy as a potential workhorse for structural components rather than a one‑off demonstration.

Why fivefold strength matters for real hardware

Multiplying the strength of aluminum by a factor of five is not just a laboratory milestone, it is a design lever for engineers working on everything from drones to electric SUVs. Higher strength at the same density allows parts to be thinner, lighter, or both, which can translate into longer range, higher payloads, or improved crash performance. In aerospace, where every kilogram saved can ripple through fuel burn and payload calculations, a printable aluminum that rivals the strength of some steels while remaining far lighter could open the door to new airframe architectures and more efficient propulsion systems.

Commentary on the MIT work has leaned into this potential, with one analysis likening the alloy to a real‑world version of “Reardon Metal” from science fiction and noting that, according to MIT’s own description, the new material can reach five times the strength of standard cast aluminum because of its engineered microstructure and carefully controlled printing parameters. That perspective is captured in a discussion of how according to MIT the alloy hits fivefold strength, turning what was once a narrative device into a benchmark for real engineering performance. For industries chasing every gram of weight savings, that kind of step change is hard to ignore.

Lessons from other advanced aluminum systems

MIT’s breakthrough does not exist in isolation. It sits within a broader push to design aluminum alloys that can handle the unique thermal and mechanical demands of modern manufacturing processes. One example comes from work on Al–Ce systems produced by additive friction stir deposition, a solid‑state technique that avoids full melting and instead plastically deforms material into place. Researchers studying these Al–Ce alloys have shown that process‑specific design strategies can deliver an exceptional balance of strength and ductility in the as‑deposited state, meaning parts come out of the machine already close to their final mechanical performance without extensive heat treatment.

Those results underscore how tailoring alloy chemistry to a particular process can unlock combinations of properties that would be difficult to achieve with a one‑size‑fits‑all composition. In the case of the Al–Ce work, the authors emphasize that these benefits, combined with the broader applicability of their alloy design strategy to other systems, underline its potential to meet the demands of diverse industrial applications, a point detailed in their analysis of process‑specific design in novel Al–Ce alloys. MIT’s printable aluminum follows the same philosophy, but applies it to fusion‑based 3D printing and leverages machine learning to navigate the design space.

A broader shift in metal 3D printing

The arrival of a five‑times‑stronger printable aluminum coincides with a broader maturation of metal additive manufacturing, where researchers are moving beyond simple single‑metal parts toward complex, multi‑material structures. At Penn State, for example, teams have demonstrated 3D printing of intricate components that combine multiple metals in a single build, going beyond what traditional welding can achieve and hinting at future parts that integrate different functions, such as structural support and thermal management, in one monolithic piece. These advances show that the field is not just about replicating existing parts with a new tool, but about rethinking what a metal component can be.

Within that context, the MIT alloy looks less like an isolated curiosity and more like a key ingredient in a new design toolkit. As one summary of the work notes, MIT engineers have achieved a major breakthrough in materials science by creating a 3D‑printable aluminum alloy that is five times stronger than standard cast aluminum, enabling lightweight, high‑performance components that can be produced additively, a capability highlighted in a description of how MIT engineers have achieved a major breakthrough. When combined with multi‑metal printing and process‑specific alloy design, such materials could enable parts that are lighter, stronger, and more integrated than anything on the factory floor today.

What comes next for MIT’s alloy and the industry

The path from a promising alloy to widespread industrial adoption runs through qualification, standardization, and cost. Manufacturers will want to know how the material behaves under fatigue, corrosion, and impact, and whether it can be produced at scale without unpredictable variability. That means extensive testing, from coupon‑level mechanical characterization to full‑scale component trials in environments like automotive suspensions, aircraft wing structures, or turbine housings. It also means working with printer makers and powder suppliers to ensure that the alloy can be produced consistently and safely in the volumes that industry demands.

At the same time, the success of this project is likely to encourage other teams to apply similar machine learning‑driven approaches to different metals, from titanium and nickel superalloys to copper and magnesium. The fact that Dec, MIT, Engineers Create, Printable Aluminum, Times Stronger Than Conventional Alloys, and What are all explicitly associated with this work in technical summaries underscores how tightly the achievement is linked to the institution’s broader push into AI‑guided materials design. As more groups adopt comparable strategies, I expect the phrase “printable” to become less about whether a metal can survive the laser and more about how far its properties can be pushed once data and computation are fully integrated into the alloy design process.

More from MorningOverview