Far below the ice and storms of the high north, scientists have pinpointed the deepest known Arctic vent system and found it bursting with organisms that should not, by any intuitive measure, be able to survive there. At depths where sunlight never reaches and pressure would crush a submarine hull, this hidden landscape is stitched together by methane, minerals and heat, and it is crowded with life that feeds on chemical energy instead of the sun. I see this discovery not as an isolated curiosity, but as the latest and clearest sign that the Arctic seafloor is far more dynamic, and far more biologically inventive, than researchers believed even a few years ago.

The new vent site sits within a broader pattern of revelations that is rapidly rewriting the map of the polar deep. From hydrothermal chimneys off Svalbard to methane hydrate mounds in the Greenland Sea, expeditions are finding ecosystems that thrive on gas seeps and hot fluids, and that may echo conditions on early Earth. The deepest Arctic vent yet identified is not just a record breaker, it is a natural laboratory for understanding how life can flourish in the most hostile corners of our own planet and perhaps on worlds far beyond it.

How scientists found the deepest Arctic vent

The push to locate the deepest Arctic vent has been a slow, methodical effort that combines sonar mapping, chemical sensing and painstaking dives with remotely operated vehicles. Researchers first had to chart subtle anomalies in the seafloor, looking for spots where warm fluids or methane bubbles disturbed the cold, dense water column. Only after those hints emerged could they send down cameras and sampling gear to confirm that a true vent field existed, with hot fluids rising from the crust and a distinct community of organisms clustered around it. The result is a site that, according to detailed reporting on Scientists Found the Deepest Known Arctic Vent, now stands as the deepest such system documented in the region and is explicitly described as Teeming With Life.

What makes this find especially striking is that it emerged from an area long written off as relatively quiet. Earlier mapping campaigns had suggested that parts of the Arctic ridge system were geologically subdued, with little volcanic or tectonic activity to drive vigorous venting. The new work overturns that assumption, revealing a vent field that is not only active but biologically rich, with dense mats of microbes and larger animals exploiting the chemical gradients around the flow. In that sense, the deepest Arctic vent is both a geographic superlative and a conceptual shock, forcing scientists to revisit where they expect to find such ecosystems and how extensive they might be beneath the polar seas.

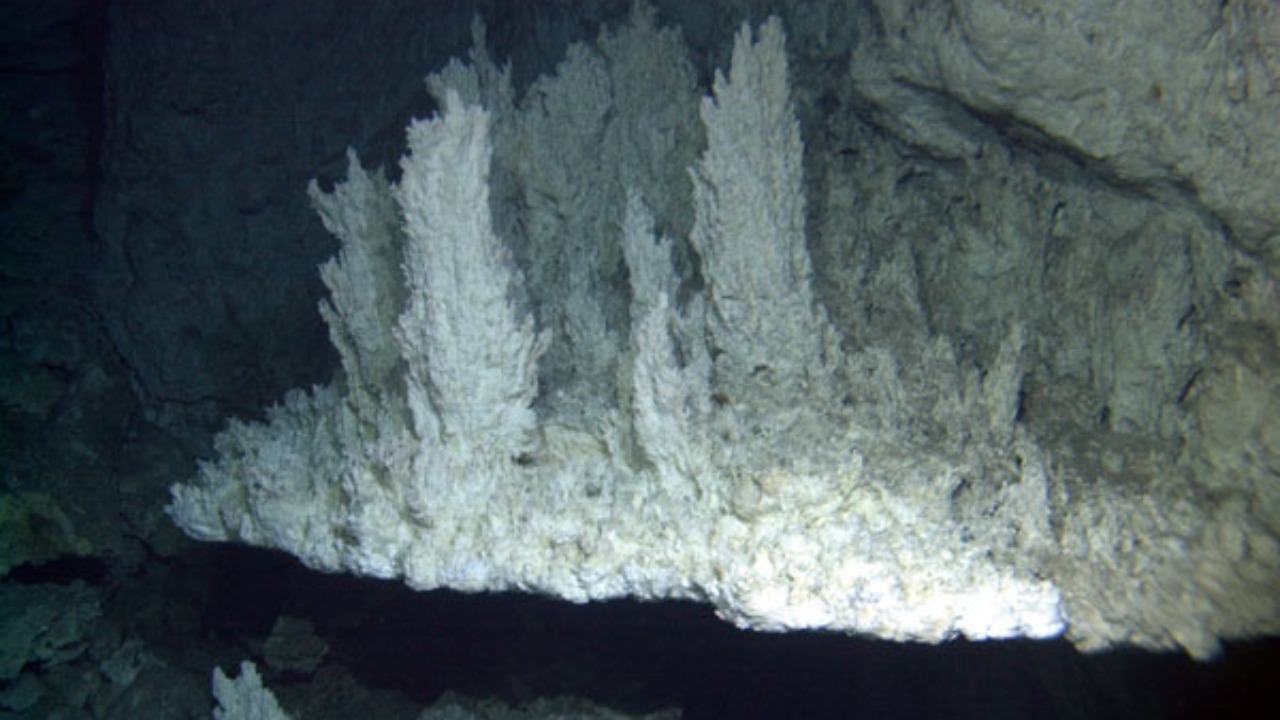

A “geologically dead” Arctic that is anything but

For years, some stretches of the Arctic seafloor were casually labeled as almost dormant, a place where plate boundaries were sluggish and hydrothermal activity would be sparse. That view has been dismantled by a series of discoveries that show intense venting and complex geology in places once thought quiet. Earlier work in the region uncovered hydrothermal structures nicknamed “Dragon” and “tree of life,” dramatic chimneys and mineral towers that rose from a ridge scientists had previously described as nearly inactive. Those features, detailed in coverage of the Dragon and tree of life hydrothermal vents, helped overturn the notion that this part of the Arctic was geologically dead.

The new deepest vent fits neatly into that reversal. Instead of a sparse scattering of minor seeps, researchers are now mapping a mosaic of vigorous hydrothermal fields and methane-rich mounds across the high north. Each fresh site adds evidence that the Arctic ridge system is more fractured, more magmatically active and more chemically diverse than older models allowed. In practical terms, that means more heat and more fluid flow, which in turn support more chemosynthetic life. The phrase “geologically dead” no longer applies, and the discovery of the deepest Arctic vent underscores how misleading that label always was.

A unique ecosystem under the Arctic ice

What scientists are finding at these depths is not just a new dot on a map, but a distinct ecosystem that operates on rules very different from those at the surface. Many kilometers down on the seafloor in the high north, researchers have documented dense microbial mats, tube worms, crustaceans and other organisms that draw their energy from methane and sulfide rather than sunlight. Reporting on how Scientists discovered a unique ecosystem under the Arctic describes how Main findings from By Amanda Schei highlight that Many of these species appear to be new to science, adapted to the crushing pressure and chemical flux of the deep.

Working in this environment is risky, which shapes what I can reasonably expect from each expedition. The same report notes that a single technical failure could mean the entire mission could be lost, a reminder that every sample and every video transect is hard won. Yet despite those constraints, the picture that is emerging is of a coherent, self-sustaining community built around the vent and seep structures. Microbes oxidize methane and hydrogen sulfide, forming the base of a food web that supports larger animals, some of which host symbiotic bacteria in their tissues. The deepest Arctic vent, embedded in this broader network of sites, appears to host its own version of that chemical economy, with life woven tightly around the flow of gas and minerals.

Freya Hydrate Mounds and the 3,640 m frontier

The clearest benchmark for just how deep and extreme these Arctic systems can be comes from the Freya Hydrate Mounds, a cluster of methane-rich structures perched at 3,640 m depth. A multinational scientific team led by UiT identified these features as the deepest known gas hydrate cold seep on the planet, describing how The di Freya Hydrate Mounds at 3,640 m depth form a striking, elevated landscape on the seafloor. These mounds are built from gas hydrates, ice-like structures that trap methane under high pressure and low temperature, and they leak that gas into the surrounding water in towering plumes.

Far from being barren, the Freya Hydrate Mounds support a thriving biological community. Detailed accounts of how Far north in the Fram Strait, near the Fram Strait, scientists from The Arctic University of Norway documented some of the tallest gas flares recorded worldwide, show that these plumes are wrapped in dense microbial growth and visited by larger animals that graze or hunt in the chemically enriched water. The Freya Hydrate Mounds therefore serve as a close cousin to the deepest Arctic vent, illustrating how methane seepage at 3,640 m can sustain a complex ecosystem and offering a direct comparison point for the newly identified vent field.

Hydrothermal vents off Svalbard and the Jøtul Field

The Arctic’s deep ecosystems are not limited to cold seeps. Off Svalbard, researchers have been investigating hydrothermal vents at depths of around 3,000 m, where hot fluids rise through the oceanic crust and erupt into the frigid water. On its way up the fluid becomes enriched in minerals and materials dissolved out of the oceanic crustal rocks, creating the classic “black smoker” effect when it hits the seawater. Work described in a project on newly discovered hydrothermal vents at depths of 3,000 meters off Svalbard notes that these fluids build both active and inactive smokers in the field, each with its own biological signature.

Further along the ridge, scientists have focused on the Jøtul Field, another hydrothermal area where they have begun to quantify the physical and chemical environment in detail. In that work, the temperature measurement at the vent outlets is a central research method, allowing teams to estimate how much heat and energy is being delivered to the ecosystem. Reporting on how Scientists Unveil Mysteries of Newly Discovered Hydrothermal Vents at this Field explains that these measurements, combined with fluid sampling and imaging, help define how the Jøtul system compares to other vents worldwide. Together, the Svalbard vents and the Jøtul Field show that the Arctic hosts a spectrum of hydrothermal environments, from moderate depth smokers to the newly recognized deepest vent, all feeding life with chemical energy.

Knipovich Ridge and a new Arctic hydrothermal field

One of the most surprising developments in recent years has been the recognition of a vigorous hydrothermal field on the Knipovich Ridge, a segment of the mid-ocean ridge system that cuts through the Arctic. In 2022, an international research team aboard a dedicated vessel mapped this area and found clear signs of intense geological activity, including venting and fresh volcanic features. Coverage of a New hydrothermal field in the Arctic emphasizes that this Arctic ridge segment is far from quiescent, with strong heat flow and active fluid circulation.

For me, the Knipovich Ridge discovery is a crucial piece of context for the deepest Arctic vent. It shows that the tectonic engine driving hydrothermal activity in the region is robust, even in places that had been poorly surveyed. The same processes that create the Knipovich field, including magma intrusion and faulting, can also generate deep vent systems elsewhere along the ridge. As mapping improves, it is reasonable, based on these findings, to expect more deep vents and seeps to be identified, filling in the gaps between known sites like the Freya Hydrate Mounds, the Jøtul Field and the newly documented deepest vent.

World’s deepest methane mounds and the Greenland Sea

The Arctic is not just setting records for vent depth, it is also home to the world’s deepest methane-seeping hydrate mounds. World reports describe how the World’s deepest methane-seeping hydrate mounds were found 11,942 feet below the Greenland Sea, where they form a dynamic habitat for life. Perched at that depth, these mounds leak methane into the water column, creating a chemical oasis that supports specialized microbes and the animals that feed on them.

The Greenland Sea mounds are not identical to the deepest Arctic vent, which is driven by hydrothermal heat rather than hydrate decomposition, but they share key features. Both are located at extreme depths, both involve focused release of methane or other reduced chemicals, and both host dense biological communities that rely on chemosynthesis. The figure of 11,942 feet is a reminder of just how deep these systems can be, and how far beyond the reach of sunlight life can extend when it has access to chemical energy. In that sense, the Greenland Sea mounds and the deepest Arctic vent are part of the same broader story, one in which methane and minerals, rather than photosynthesis, define the boundaries of habitability.

Aurora and the search for life beyond Earth

Long before the latest record-breaking vent was confirmed, scientists had already recognized that Arctic hydrothermal systems could serve as analogs for environments on other worlds. The vent site known as Aurora, discovered in the Arctic in 2014, quickly became a touchstone for thinking about how life might arise and persist in icy oceans elsewhere in the solar system. An international team of researchers has used Aurora to explore how hydrothermal circulation can continue even when the overlying crust spreads at only about a centimeter per year, a detail highlighted in reporting on Aurora in the Arctic and its implications for the search for extraterrestrial life.

The deepest Arctic vent now adds a new dimension to that analogy. If life can thrive at such depths, under such pressure and in such cold, then similar ecosystems might be possible in the subsurface oceans of moons like Europa or Enceladus, where tidal heating could drive hydrothermal activity beneath thick ice. I see the Arctic vents, from Aurora to the Freya Hydrate Mounds and the new deepest site, as a continuum of natural experiments that test the limits of biology. Each one refines the parameters scientists use when they model potential habitats on other worlds, from the required heat flow to the chemistry of the fluids that sustain chemosynthetic microbes.

Methane, oil and strange life forms at Freya Hydrate Mounds

Among all these sites, the Freya Hydrate Mounds stand out not only for their depth but for the complexity of their chemistry. Scientists discovered the Freya Hydrate Mounds 3,640 m below the Arctic, revealing a methane-rich ecosystem with unique combinations of gas, oil and biological activity. Detailed accounts of how Scientists discovered the Freya Hydrate Mounds during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep expedition describe how this Arctic site hosts strange life forms that appear to be finely tuned to the mix of methane and oil seeping from the mounds.

For me, the Freya system is a warning as well as a wonder. The same methane that feeds its microbes is a potent greenhouse gas if it escapes to the atmosphere, and the presence of oil hints at deeper reservoirs that could be disturbed by future human activity. The fact that such a delicate, specialized ecosystem exists at 3,640 m depth suggests that any disruption, whether from climate-driven changes in ocean circulation or from resource exploration, could have outsized effects. When I compare Freya to the newly identified deepest Arctic vent, I see two sides of the same coin: both are remote, chemically rich habitats that expand our sense of where life can flourish, and both are vulnerable to changes that originate far above the seafloor.

More from MorningOverview