Russian researchers have pulled off a feat that sounds closer to science fiction than standard lab work, reviving microscopic “zombie worms” that had been locked in Arctic ice for roughly 24,000 years. The organisms, known as bdelloid rotifers, did not just twitch back to life, they ate, moved, and reproduced as if the last ice age had ended yesterday.

By coaxing these ancient animals out of suspended animation, scientists have opened a rare window into extreme survival strategies that blur the line between life and death. I see this experiment not only as a startling story about frozen creatures waking up, but as a test case for how biology might endure climate upheaval on Earth and, one day, hostile conditions far beyond it.

Unearthing a 24,000-Year-Old survivor

The core of the discovery is deceptively simple: a team of Russian scientists drilled into Siberian permafrost and recovered tiny animals that had been entombed since long before human civilization took shape. These bdelloid rotifers were trapped in frozen sediment for an estimated 24,000 years, a figure that turns a microscope slide into a time capsule from the late Pleistocene. When the ice finally yielded, the animals did not emerge as fossils or fragments, but as intact, viable bodies capable of rejoining the living world.

What makes this so striking is not just the age of the sample, but the completeness of the revival. The rotifers were revived from a state that researchers describe as cryptobiosis, a kind of biological pause button that allowed them to survive the deep freeze without apparent structural damage. In reports on the work, the experiment is framed as Russian Scientists Brought 24,000-Year-Old Old Zombie Worms Back Life, a phrase that captures both the precise age estimate and the eerie sense that something impossibly old has been jolted awake in the present day, with Dec and Here used to mark the context of the finding in the broader discussion of ancient life.

What exactly are these “zombie worms”?

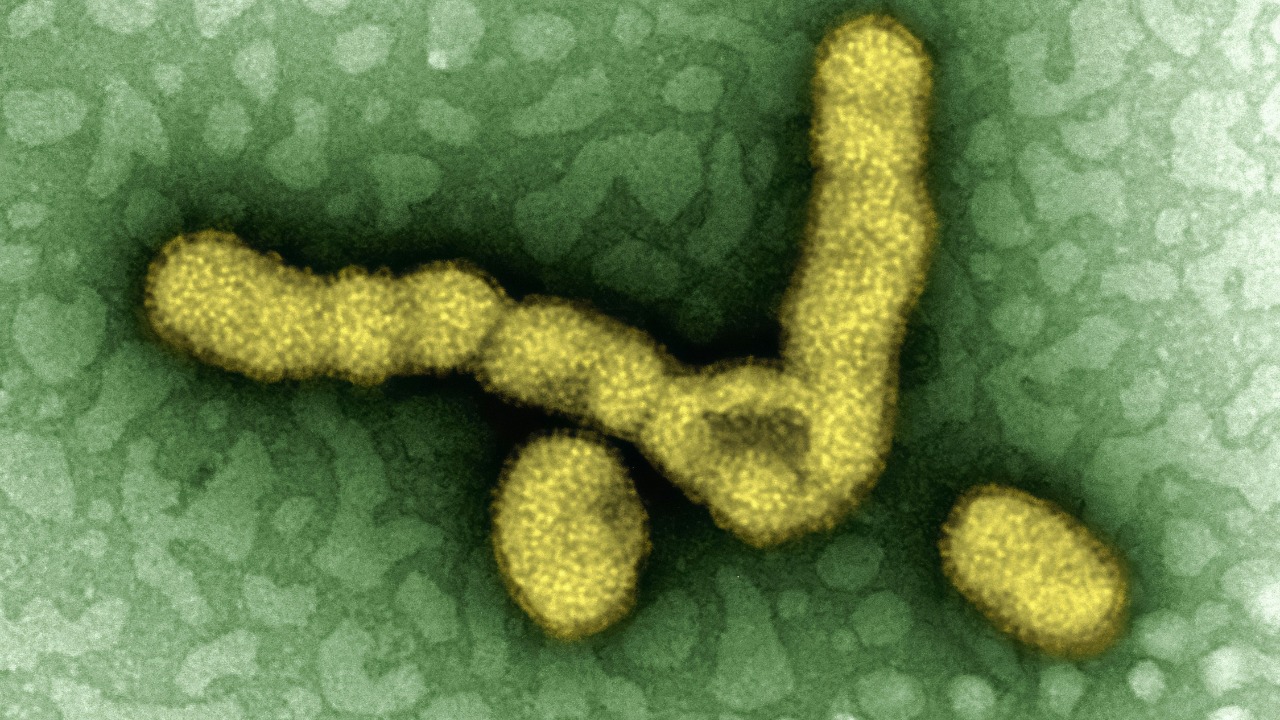

Despite the nickname, these creatures are not worms in the earthworm sense, and they are certainly not undead. Bdelloid rotifers are microscopic aquatic animals, often less than a millimeter long, that live in water films on moss, in freshwater puddles, and in thin layers of soil. Under a microscope, they look like tiny cylinders with a wheel-like crown of cilia at one end, which they use both for swimming and for sweeping food particles into their mouths. Their bodies are segmented and flexible, allowing them to inch along surfaces or curl into tight balls when conditions turn harsh.

Biologically, bdelloid rotifers are already outliers before anyone starts freezing them for geological epochs. They are famous for reproducing without males, relying on asexual reproduction to generate new generations, and for shrugging off insults that would kill most animals. In a survey of hardy species, they are singled out as Bdelloid Rotifers that survived being frozen in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years, a feat that places them alongside other organisms that almost cannot be killed, yet still sets them apart because their resilience depends on a sophisticated form of suspended animation that other animals cannot replicate.

How Russian scientists brought them back

Reviving an organism that has been frozen for tens of thousands of years is not as simple as letting an ice cube melt on a lab bench. The Russian team had to extract intact cores of permafrost, keep them uncontaminated, and then gently warm the samples in controlled conditions so that any surviving organisms would not be shocked into death as the ice thawed. Once the sediment softened, the scientists carefully isolated microscopic life, watching for any sign of movement or feeding that would indicate genuine revival rather than contamination from modern organisms.

To make sense of what they were seeing, the researchers leaned on the concept of cryptobiosis, the state in which organisms effectively shut down their metabolism to survive extremes of cold, dryness, or lack of oxygen. In detailed accounts of the work, cryptobiosis is described as critical because organisms must protect their cells and DNA during the freeze and then manage the delicate transition back to activity without catastrophic damage. The team studying the rotifers and other extremophile organisms in this permafrost relied on that principle, gradually waking the animals back up and then observing how they fed and reproduced once they had fully emerged from their 24,000-Year-Old slumber, a process that is laid out in depth in analyses of how Russian Scientists Brought these Old Zombie Worms Back Life in Dec Here.

From frozen “zombie” to active animal

Once the rotifers were coaxed out of the ice, the question was whether they were merely twitching or truly alive in every functional sense. The answer came quickly. The animals began to move with purpose, using their cilia to swim and to pull food particles toward their mouths. They responded to stimuli, changed direction, and behaved like their modern relatives that live in ponds and wet moss. This was not a partial revival or a one-off reflex, it was a full return to active life after a pause that spanned the rise and fall of ice sheets.

Reports on the discovery describe how these Frozen organisms, recovered by Russian researchers, had been locked in Arctic permafrost for 24,000 years before being brought back to life in the lab. In one account, the story is framed as Frozen “zombie” worms brought back to life after 24,000 years, with Jun used to situate the timing of the public revelation and Russian scientists credited with the painstaking work of thawing and monitoring the animals. The key detail is that the rotifers did not just survive the thaw, they resumed normal biological functions, including reproduction, which confirms that their long freeze was a reversible state rather than a slow path to decay.

Cryptobiosis: life on pause

To understand how any animal can endure 24,000 years in ice, I have to focus on cryptobiosis, the survival strategy that turns metabolism down so low it is almost undetectable. In this state, rotifers lose most of their body water, stabilize their cellular structures with protective molecules, and effectively suspend the chemical reactions that would otherwise tear them apart in extreme cold. It is not sleep and it is not death, it is a third category in which life is preserved as potential, waiting for the right conditions to resume. The fact that rotifers can enter and exit this state repeatedly over their normal lifespans hints at why a single, very long cryptobiotic episode in permafrost might be survivable.

In detailed explanations of the phenomenon, cryptobiosis is described as critical because organisms must both protect themselves during the freeze and then navigate the treacherous process of waking back up. If ice crystals form inside cells, they can shred membranes and DNA, so the animals rely on biochemical tricks to avoid that fate, then reverse those changes when warmth and liquid water return. The researchers who studied the rotifers and other extremophile organisms in Siberian permafrost emphasize that successfully waking back up is as challenging as surviving the freeze itself, which is why the controlled thawing protocols used when Russian Scientists Brought 24,000-Year-Old Old Zombie Worms Back Life in Dec Here are as central to the story as the initial descent into cryptobiosis.

Why bdelloid rotifers are almost unkillable

Even before they became poster animals for ancient survival, bdelloid rotifers had a reputation for being nearly indestructible. They can survive being dried out, blasted with radiation, and exposed to toxic chemicals that would obliterate more delicate creatures. Their DNA repair systems are unusually robust, allowing them to patch up damage that accumulates when they are in cryptobiosis or when they are hit with environmental stress. This resilience is not a party trick, it is a core part of their life history, letting them colonize unstable habitats that regularly swing between wet and dry or freeze and thaw.

In broader discussions of hardy animals, bdelloid rotifers are singled out as Bdelloid Rotifers that survived being frozen in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years, a benchmark that places them in a select group of organisms that almost cannot be killed. The same reporting notes that in 2021, scientists revived rotifers from Siberian permafrost that had been frozen for 24,000 years, underscoring that this is not a hypothetical capability but a documented event that other animals cannot replicate. When I look at that record, it is clear that the “zombie worm” label undersells what is going on here, these are not mindless revenants, they are highly evolved survivors with a toolkit that lets them ride out catastrophes that would erase most forms of life.

What the revival tells us about ancient ecosystems

Bringing a 24,000-year-old rotifer back to life is not just a stunt, it is a way to sample an ecosystem that no longer exists. The permafrost that held these animals formed in a climate very different from today’s, with ice sheets advancing and retreating and megafauna like mammoths roaming the landscape. By reviving organisms from that frozen archive, scientists can study how life adapted to those conditions, what kinds of microbes and small animals shared the habitat, and how food webs functioned at the microscopic scale. Each revived rotifer is a data point in a much larger reconstruction of Pleistocene biology.

The fact that these animals are bdelloid rotifers, with their unusual reproductive strategies and extreme resilience, adds another layer to that story. Their presence in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years suggests that they were already exploiting cryptobiosis as a survival strategy in ancient environments, not just in modern ponds and moss beds. When I connect that to accounts that highlight Bdelloid Rotifers from Siberian deposits as among the 10 animals that almost cannot be killed, it becomes clear that their evolutionary success is tied to their ability to bridge vast stretches of time, effectively skipping over hostile eras and reappearing when conditions improve.

From Siberian ice to Instagram science marvel

Scientific breakthroughs often live quiet lives in journals and conference talks, but the idea of 24,000-year-old “zombie worms” waking up was always going to escape that orbit. The story has been framed as a real-world scientific marvel in popular accounts, with Russian scientists credited for reviving bdelloid rotifers that had been frozen for tens of millennia. The combination of a catchy nickname, a clean narrative arc from ice to life, and the unsettling implication that ancient organisms can rejoin modern ecosystems has made the discovery a natural fit for social media feeds and science explainers.

One widely shared description captures the tone succinctly, describing how, in a real-world scientific marvel, Russian researchers revived bdelloid rotifers, microscopic “zombie worms” that had endured in permafrost for thousands of years, with Aug used to situate the discussion and Russian scientists placed at the center of the achievement. I see that public fascination as more than a curiosity, it reflects a growing appetite for stories that challenge our assumptions about what life can survive, and for glimpses of research that might one day inform technologies for long-term preservation, space travel, or even medical applications that borrow from the rotifers’ cryptobiotic tricks.

Why this matters for the future of life on Earth

It is tempting to treat the revival of 24,000-year-old rotifers as a one-off oddity, but the implications reach far beyond a single lab. As climate change accelerates the thawing of permafrost, more ancient organisms, from microbes to small animals, are likely to be released into modern ecosystems. The rotifers show that at least some of those organisms may not be dead relics, but viable life forms capable of waking up and interacting with today’s biosphere. That raises questions about ecological impacts, disease risks, and the long-term feedbacks between a warming climate and the frozen archives it unlocks.

At the same time, the rotifers’ success story offers a blueprint for resilience. Their ability to enter cryptobiosis, protect their cells for 24,000 years, and then resume normal life suggests that biology has solutions to extreme stress that we are only beginning to understand. When I connect the detailed accounts of how Russian Scientists Brought 24,000-Year-Old Old Zombie Worms Back Life in Dec Here with broader surveys that place Bdelloid Rotifers from Siberian permafrost among the toughest animals known, I see a convergence of evidence that these microscopic creatures are not just curiosities from the past, they are guides to how life might endure the shocks of the future, whether those shocks come from climate change, deep space travel, or technologies that demand putting living systems on pause and bringing them back intact.

More from MorningOverview