For decades, deep space exploration has depended on a handful of obscure isotopes quietly heating small nuclear batteries on robotic probes. Now a different, even less familiar element is moving to the center of that story, promising to keep spacecraft powered for centuries instead of decades and to loosen a critical supply bottleneck. Americium, best known as the material inside household smoke detectors, is emerging as the tiny workhorse that could define how far and how boldly space agencies push into the outer Solar System.

As the United States, Europe and their partners sketch out missions to the dark reaches beyond Jupiter, they are converging on americium‑241 as the next strategic fuel for radioisotope power systems. I see a clear pattern in the reporting: laboratories are proving the physics, agencies are lining up industrial partners, and engineers are redesigning power units around this isotope’s unusual longevity, even as some scientists warn that the race to deploy a stronger nuclear fuel is moving faster than the safeguards around it.

Why deep space needs a new nuclear workhorse

Every ambitious mission that travels far from the Sun eventually runs into the same hard limit: solar panels stop being practical once light becomes too weak or intermittent. Spacecraft that must operate in permanent shadow, under thick atmospheres or at the frozen edge of the Solar System rely instead on compact nuclear batteries that convert the heat from decaying isotopes into electricity. Those radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs, have powered everything from the Apollo surface experiments to the Voyager probes, but they have also been constrained by a single fuel, plutonium‑238, that is scarce, expensive and optimized for missions measured in decades rather than centuries.

As agencies plan more complex operations in regions where sunlight is unreliable, such as the polar craters of the Moon or the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, they are looking for power sources that can outlast multiple mission phases and even support follow‑on landers or orbiters. European planners have framed this as part of a broader push to mature disruptive hardware, from advanced propulsion to new power systems, under their long term technology roadmaps, which highlight how the Sun “never stops shining” but also how missions into shadowed regions demand alternative energy by the end of this decade, a point underscored in ESA’s technology planning. In that context, the search for a more abundant, longer lived isotope is not a niche materials problem, it is a strategic enabler for the next wave of exploration.

Americium 241: the element hiding in plain sight

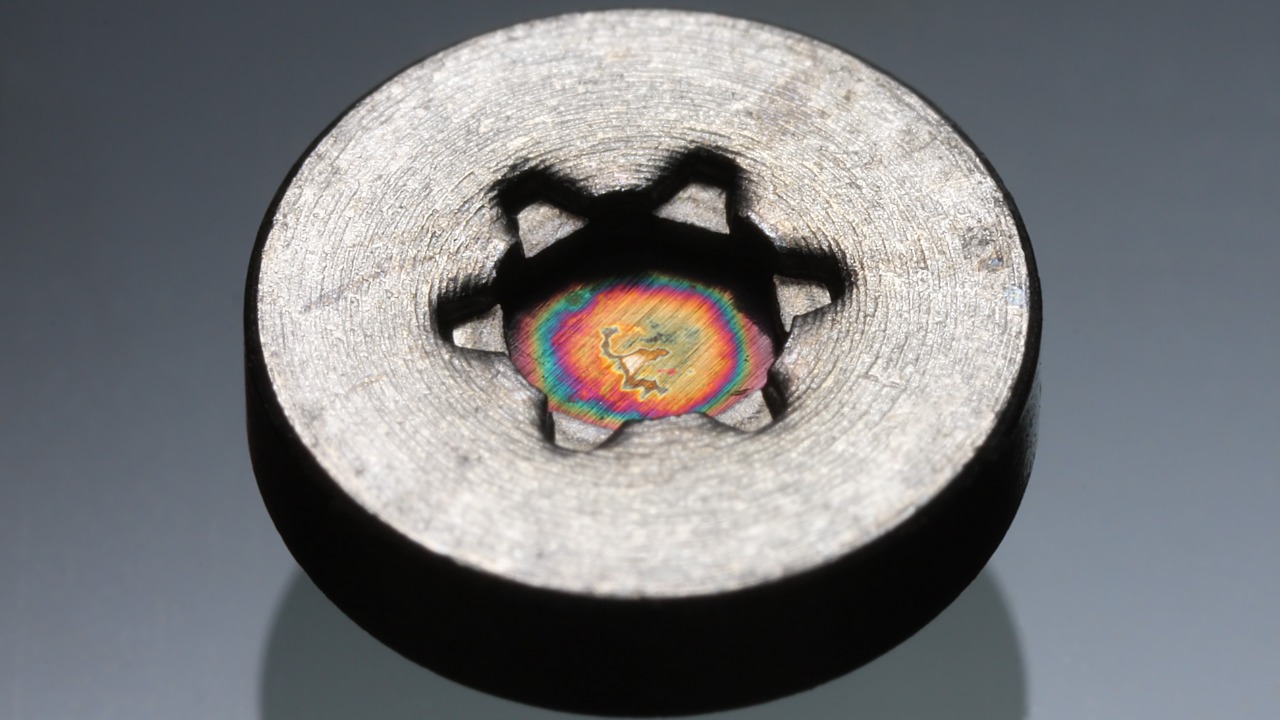

Americium has been part of daily life for years, quietly embedded in ionization smoke detectors, but only recently has it been treated as a serious contender for space power. The isotope of interest, americium 241, sits in the same actinide family as plutonium and uranium, yet it has largely been treated as a byproduct of nuclear fuel cycles rather than a prized resource. That is starting to change as researchers point out that the same properties that make it useful for sensing tiny amounts of smoke also make it a stable, predictable heat source when packaged correctly.

Technical assessments describe americium as one of the few isotopes that can deliver meaningful thermal output while also being available at scale from existing nuclear material streams. One detailed analysis notes that Americium is one of the rare elements that can provide several watts of thermal power per gram, enough to make compact RTGs viable for long duration missions. That combination of energy density and accessibility is what has turned americium 241 from an overlooked waste product into a candidate to reshape how engineers think about nuclear batteries.

From plutonium 238 to americium 241: a shift in strategy

The pivot toward americium 241 is driven as much by supply constraints as by physics. For years, mission planners have warned that limited stocks of plutonium‑238 could cap the number and scale of RTG powered spacecraft. Internal research at Los Alamos has been explicit that, due to limited supplies of plutonium‑238, agencies are evaluating americium as an alternative, noting that americium’s half life of 432 years compared with plutonium’s 88 years offers a fundamentally different performance profile, a contrast spelled out in a Los Alamos analysis of 432 versus 88 years. That longer half life means less power at the very beginning of a mission but a much slower decline over time, which is exactly what outer Solar System probes need.

In parallel, engineers have been modeling how an americium based RTG would differ from a plutonium unit in size, shielding and efficiency. One technical discussion of RTG design explains that an americium‑241 system would likely be larger and produce less initial power than a plutonium‑238 unit, but it would maintain a higher fraction of its output over long durations, a tradeoff that becomes attractive for missions that must operate for half a century or more, as explored in a detailed comparison of How an americium 241 RTG would differ from one using plutonium 238. The strategic calculus is shifting from maximizing early mission power to maximizing total lifetime energy, and americium 241 fits that new brief.

Europe’s quiet lead in americium RTGs

While the United States has dominated plutonium‑based RTG production, European organizations have quietly built a lead in americium 241 research and development. Specialists there have emphasized that americium 241 has a half life of around 430 years compared to around 90 years for plutonium 238, a ratio that makes it more suitable for missions that must survive for generations rather than decades, as highlighted in a case study noting that Not only that, but Americium 241 has a half life of around 430 years compared to around 90 years for Plutonium 238. European engineers have been explicit that they see this as a way to leverage material they already have in abundance rather than relying on imported plutonium.

Commentary on long range mission concepts has pointed out that Europeans are developing their own RTG using Americium 241, accepting that such units would be less powerful at launch but would have a much longer decay time, a tradeoff that becomes attractive for probes that might travel hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun, as described in an analysis of how the Europeans are developing their own RTG using Americium 241. That long view aligns with European Space Agency ambitions to send spacecraft into deep space environments where maintenance or refueling are impossible, making americium’s slow, steady heat output a strategic asset rather than a curiosity.

NASA, ESA and the new industrial ecosystem around americium

In the United States, americium 241 has moved from theoretical option to active test fuel. Earlier this year, NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland partnered with university and industry teams to evaluate how americium‑based heat sources could replace plutonium in the agency’s longest missions. Reporting on that effort notes that the goal is to deliver power that outlasts decades, enabling probes to operate in the harsh environments around the moons of Jupiter and Saturn without relying on dwindling plutonium stocks, a shift described in coverage of how Power that outlasts decades is central to NASA’s americium 241 plans. That work is part of a broader push at Glenn to rethink how RTGs are assembled and tested so they can accommodate different isotopes without redesigning entire spacecraft.

Europe is moving in parallel but with a stronger industrial focus. The European Space Agency has contracted the nuclear company Framatome to industrialize sealed fuel sources that use americium 241 as the fuel for radioisotope power systems, a step that shifts americium from lab scale experiments to production line planning, as detailed in the announcement that Framatome To Collaborate With European Space Agency On Radioisotope Power Systems using 241 as the fuel source. That kind of contract signals that ESA is not just experimenting with americium but is preparing to field it on operational missions, with a supply chain that can deliver standardized heat sources for multiple spacecraft over many years.

The physics that make americium different

At the core of americium’s appeal is a simple physical fact: its nuclei decay more slowly than plutonium’s, which stretches out the energy release over a much longer period. Technical reviews of alternative RTG fuels have highlighted americium 241 as a standout candidate, with one study by Dustin and Borrelli modeling nine potential isotopes and concluding that americium 241 could enable deeper exploration than was possible before, thanks to its balance of half life, power density and availability, a conclusion summarized in a discussion of Americium 241 as RTG Fuel in work by Dustin and Borrelli. That kind of modeling gives mission designers confidence that they can trade some early power for a much longer plateau of usable energy.

Other analyses quantify the advantage more bluntly, noting that americium 241’s half life of around 430 years compared with plutonium 238’s roughly 90 years means that an americium RTG will still be producing a significant fraction of its initial heat centuries after launch, even if its starting wattage is lower. European case studies emphasize that this makes americium more suitable for missions that must operate in the dark for generations, while American research underscores that it also eases the pressure on limited plutonium 238 production capacity, as seen in technical notes that The significant advantage of using 241 is that it provides a half life of 432 years compared to Plutonium. In practice, that means a probe launched in the 2030s could still be sending back data in the 2200s, powered by the same compact heat source.

From Voyager’s legacy to a new generation of nuclear batteries

The case for americium 241 is often framed against the backdrop of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which have been operating in interstellar space for decades on plutonium‑238 RTGs. Those spacecraft proved that nuclear batteries can keep instruments alive far beyond the orbit of Neptune, but their power output has steadily declined as plutonium’s shorter half life eats away at the available heat. Analysts now argue that if similar missions were launched with americium 241, they could maintain higher power levels much deeper into interstellar space, effectively extending the scientific return without changing the spacecraft design, a point made in discussions of how Europe is already pursuing americium to power spacecraft in space for hundreds of years. The idea is not to replace the Voyager legacy but to stretch it across multiple centuries.

Advocates of americium 241 argue that this shift could redefine what counts as a “long duration” mission. Instead of designing probes to last 20 or 30 years, agencies could plan for operational lifetimes measured in human generations, with RTGs that still deliver useful power after 100 years or more. That vision is echoed in forward looking commentary that describes americium as a revolutionary element set to transform space exploration, suggesting that with the advent of americium based power systems, humanity’s reach into the cosmos could extend far beyond current limits, a claim captured in the argument that With the advent of americium humanity’s reach into the cosmos will expand. In that framing, americium 241 is not just a new fuel, it is a way to rewrite the timeline of exploration.

Engineering and safety: why some scientists say “Not Ready”

For all the enthusiasm, the move to americium 241 is not without critics. Some scientists and policy experts argue that the race to deploy a nuclear fuel stronger than plutonium is outpacing the development of safety frameworks and international norms. One pointed critique carries the headline phrase “Not Ready” and warns that as NASA tests nuclear fuel stronger than plutonium, the risks of a space race spiraling out of control grow if agencies do not coordinate on launch safety, accident response and end of life disposal, concerns captured in a report titled Not Ready Scientists React To NASA Nuclear Fuel Stronger Than Plutonium As Space Race Risks Spiral Out Of. Those critics are not opposed to americium itself, but to what they see as a rush to field it without a full public debate.

Engineers inside NASA and ESA counter that they are building on decades of experience handling plutonium‑238 and that americium 241 will be subject to the same or stricter containment standards. NASA officials have highlighted that their innovative approach to testing new heat source fuel is designed to enable deeper exploration in environments where the Sun or other environmental barriers make solar power impossible, while still keeping launch risks within established bounds, a balance described in agency updates that emphasize how Public Affairs Specialist updates on tests of new heat source fuel reference work in the Thermal Energy Conversion Branch and past two decades in Europe. The debate is less about the physics of americium and more about how quickly the world is comfortable putting more nuclear material on top of rockets.

From lab curiosity to cornerstone of future missions

What stands out in the current reporting is how quickly americium 241 has moved from a theoretical option to a central pillar of mission planning. Technical briefings now describe americium as a small element that could power the next century of space exploration, noting that scientists believe a new fuel can make nuclear batteries so special that they become the default choice for deep space missions, a sentiment reflected in analyses that explain how Now scientists believe a new fuel makes nuclear batteries so special. That shift is not just about swapping one isotope for another, it is about reimagining what kinds of missions are technically and economically feasible.

Los Alamos researchers have gone so far as to describe a “United States of Americum,” a play on words that underscores how central americium‑241 could become to national space strategy. Their reports explain that Americum‑241 has been proposed as an alternative to plutonium‑238 for use in RTGs and that new chemical processes are being developed to recover the americium‑241 from existing nuclear materials, a process outlined in technical notes that Americum 241 has been proposed as an alternative to plutonium 238 and processes are being developed to recover the americium 241. When national laboratories start redesigning their separation lines around a new isotope, it is a sign that the element has moved from curiosity to cornerstone.

The stakes: who controls the tiny element that powers the next century

As americium 241 moves into the mainstream of space power planning, the geopolitical stakes are becoming clearer. Countries that can produce, process and safely launch americium based RTGs will have a structural advantage in sending probes to the outer planets, operating long lived surface stations on the Moon and Mars, and fielding autonomous platforms in permanently shadowed regions. European technology roadmaps already frame americium RTGs as part of a broader portfolio of “tomorrow’s technology” that will keep ESA competitive in exploration and science, a framing reinforced in strategy documents that describe how The Sun never stops shining but new power systems are needed by the end of this decade. In the United States, the push to secure americium supplies is intertwined with broader debates over nuclear infrastructure and space leadership.

Looking ahead, I expect the story of americium 241 to be told less in laboratory half life charts and more in mission profiles: landers that survive the lunar night without massive batteries, orbiters that keep mapping icy moons long after their solar powered cousins have gone dark, and interstellar probes that continue sending back data to grandchildren of the engineers who launched them. Analysts already talk about Americium, How a long life nuclear fuel will transform space exploration, and they point to early mission concepts that would rely on americium powered RTGs to push humanity’s robotic presence far beyond the current frontier, a vision encapsulated in forward looking pieces that describe Americium How a long life nuclear fuel will transform space. The element that once hid inside smoke detectors is on track to become the quiet, persistent heartbeat of the next century in space.

More from MorningOverview