The small black cylinder near the end of many power and data cables is not a decorative lump of plastic, it is a deliberate piece of engineering that keeps your gadgets talking clearly in a noisy electronic world. Hidden inside is a material that tames high frequency interference so your laptop, router, game console, or monitor can operate smoothly without random glitches or mysterious dropouts. Once you understand what that component does, it becomes a quiet hero of everyday reliability rather than a mysterious bump on the wire.

I see that same component across USB hubs, HDMI leads, and laptop chargers, and it is doing the same job every time: protecting both the device and everything around it from unwanted electrical noise. It is a simple, passive part, but it sits at the center of how modern electronics share crowded power strips, Wi‑Fi bands, and office desks without constantly crashing into each other.

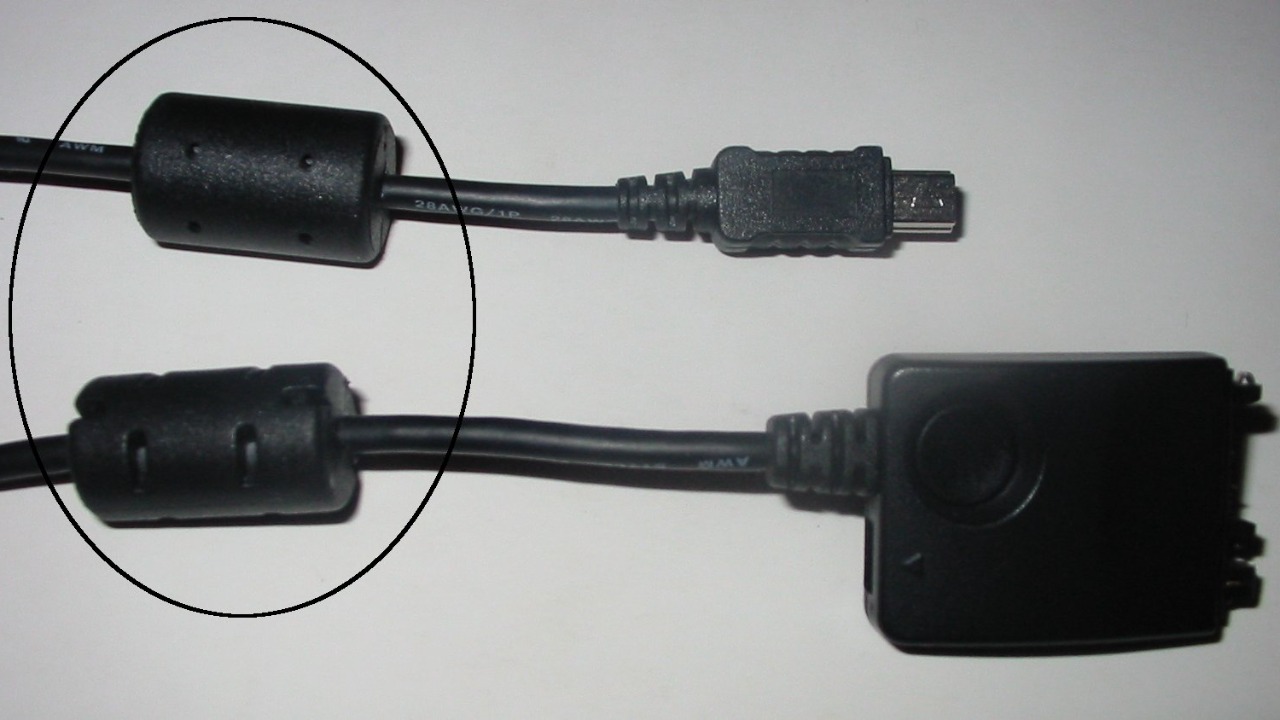

What that “mystery cylinder” actually is

The black cylinder is usually a ferrite bead, sometimes called a ferrite block, ferrite core, ferrite ring, EMI filter, or ferrite choke, and it is made from a ceramic-like material rich in iron oxide that is tuned to interact with high frequency signals. In plain terms, it is a small component that resists and dissipates fast, noisy currents while letting the slower, useful power or data keep flowing. Engineers group these parts under the broader family of Ferrite devices, and they are a standard tool for controlling EMI in electronic circuits.

On the outside, the bead is encased in a molded shell that matches the cable jacket, which is why it looks like a simple plastic bulge. If you were to cut that shell open, you would find a dense, black metal cylinder that the cable passes through or wraps around, exactly as described in explanations of the bumps at the end of Computers cables. The geometry can vary, from a simple ring to a split core that clips around an existing wire, but the principle is the same: the ferrite material surrounds the conductor so it can soak up unwanted high frequency energy.

Why cables need help in a noisy electronic world

Modern homes and offices are saturated with devices that radiate and receive radio frequency energy, from Wi‑Fi routers and Bluetooth earbuds to induction cooktops and LED lighting. Every cable in that environment can act like an antenna, unintentionally picking up or radiating interference that rides along the wire and sneaks into sensitive circuits. When you use a cable to charge or power your everyday devices, you are not just moving electricity, you are also creating a potential pathway for stray signals that can disrupt how those devices operate, which is why manufacturers add components so everything can operate smoothly without disruption, as detailed in breakdowns of Here is what those cylinders are for.

Regulators also care about this noise, because a poorly shielded cable can cause a laptop or charger to exceed legal limits on electromagnetic emissions and interfere with nearby radios or televisions. Engineers talk about EMI as both emissions (what your device leaks out) and susceptibility (how easily it is disturbed by outside signals), and both sides of that equation are affected by the wiring that connects devices together. The ferrite bead on a cable is one of the simplest ways to keep those emissions and susceptibilities under control so that a single misbehaving cord does not become the loudest antenna in the room.

How ferrite beads tame interference without killing your signal

Ferrite beads work by presenting a frequency dependent impedance to the current flowing through the cable, which means they resist fast changes much more than slow ones. The direct current that powers a laptop or the relatively low frequency components of a USB or HDMI signal pass through with little loss, but the high frequency noise that rides on top of those signals is choked off and converted into a tiny amount of heat. In EMI jargon, the bead acts as a lossy inductor that targets the very frequencies that tend to cause trouble in nearby radios and sensitive circuits, which is why designers rely on Ferrite Chokes as One common filter element when they need a last resort to reduce cable emissions or susceptibility.

In practice, that means the bead is tuned so that the useful signal sees the cable as almost unchanged, while the unwanted high frequency components see a much more difficult path. The result is a cleaner waveform at the device end, fewer spurious emissions radiating from the cable, and a lower chance that a nearby radio, television, or wireless microphone will pick up a buzz or whine. Because the ferrite is passive and self contained, it does this job without needing power, software, or any user intervention, which is why it has become such a ubiquitous, low drama fix for interference problems.

Where you are most likely to see these cylinders

Once you start looking for them, ferrite cylinders show up on a wide range of cords, from laptop power bricks and desktop monitor cables to USB printer leads and some HDMI or DisplayPort connections. They are especially common on cables that connect to computers, because those systems combine fast digital electronics with long external wires that can easily behave like antennas. A closer look at the bumps at the end of computer cables shows that the bead is encased in plastic and that all you would find inside is a black metal cylinder, which matches what you see on many monitor and peripheral cords that ship with desktop cables.

They also appear on some power adapters for game consoles, routers, and external hard drives, particularly when the manufacturer expects the device to sit near audio or radio equipment. Not every such cable has a ferrite core, and one detailed purge of old cords found that only about one quarter of the power and data cables in that sample carried a visible cylinder or box, a reminder that designers only add them when they are needed to meet EMI limits or solve a specific interference problem, as noted in a discussion of the Oct mystery bumps on cords. If you see a cable without one, it may simply mean the device passed its regulatory tests without needing the extra help.

Inside the plastic: magnets, myths, and what users get wrong

Because the cylinder is hidden and unlabelled, it has inspired plenty of speculation, from secret surge protectors to data security modules, but the reality is more mundane and more useful. At a basic level, it is a chunk of ferrite material that behaves like a specialized magnet for high frequency currents, not a smart chip or active filter. One early online explanation captured the confusion when a commenter said they were pretty sure all of them are just a magnet (or magnets) and admitted they were not 100% sure on their purpose, before others clarified that it is a ferrite core used to suppress interference, as laid out in a Dec thread on what that cylinder is.

That misunderstanding matters because it shapes how people treat the component, with some assuming it is optional or purely cosmetic and others worrying that it stores data or affects charging speed. In reality, the bead does not know or care what information is flowing through the cable, it simply resists the high frequency parts of the current that can cause trouble elsewhere. Removing it will not unlock extra performance, and adding one to a cable that does not need it will not magically boost speed, but in the right place it can be the difference between a stable connection and a maddening pattern of random glitches.

How ferrite cylinders protect your gear from real world problems

In everyday use, the most obvious benefit of these cylinders is the absence of problems you might otherwise blame on software bugs or flaky hardware. A noisy power line can inject interference into a laptop charger, which then travels along the cable and into the computer, where it may cause subtle data errors or make the system more likely to crash under certain conditions. By choking off that high frequency noise at the cable, the ferrite bead helps the device avoid those edge case failures and keeps the user experience boring in the best possible way, something that is easy to overlook until you have lived with a setup that lacks proper EMI control.

The same principle applies in the other direction, where a powerful graphics card or switching power supply inside a desktop can generate interference that rides out along the monitor or USB cables and radiates into nearby audio gear or radios. Engineers and hobbyists who troubleshoot these issues often reach for clip-on ferrite rings to kill power line interference, because Sometimes it does not matter, but other times it can give rise to interference on radios, televisions and the like, as demonstrated in practical guides to Sometimes using ferrite rings. The factory installed cylinder on a cable is simply a built in version of that same fix, tuned and tested for the specific device.

Why some cables have them and others do not

Manufacturers do not add cost and bulk to a cable without a reason, so the presence of a ferrite cylinder is usually a sign that the device needed extra help to meet EMI requirements or to behave well in a noisy environment. Devices that switch large currents quickly, such as laptop chargers or external power bricks, are prime candidates, as are cables that carry high speed digital signals over longer distances, where the wire can act like a more efficient antenna. In those cases, the ferrite bead is a relatively cheap insurance policy that helps the product pass regulatory tests and reduces the risk of customer complaints about interference or instability.

On the other hand, many short, well shielded cables can meet the same standards without a visible cylinder, especially when the device at each end already includes internal filtering. Not every such cable has a ferrite core, and one survey of cords found that only about one quarter of the power and data cables in that batch had any kind of ferrite block or box, which underscores that designers treat these components as targeted fixes rather than default decorations, as described in the analysis of why Not every cord carries the extra hardware. If you see two otherwise similar cables and only one has a cylinder, it likely reflects differences in the devices they were built to serve, not a simple quality ranking between the cords themselves.

When that little cylinder can actually “save” a setup

There are situations where the presence or absence of a ferrite bead can make the difference between a usable system and one that constantly misbehaves. In home studios, for example, musicians often battle a faint digital whine in their speakers that tracks with mouse movement or hard drive activity, a classic sign that computer noise is leaking into the audio path through USB or power cables. Swapping in a cable with a properly placed ferrite cylinder, or adding a clip-on ring near the interface, can dramatically reduce that noise by blocking the high frequency components that were coupling into the audio gear, a real world illustration of how Ferrite chokes serve as a last resort to reduce susceptibility.

Similar stories play out around ham radio setups, where long Ethernet or HDMI cables can inject noise into sensitive receivers, and in offices where a particular monitor cable seems to make nearby speakers buzz whenever the screen shows high contrast patterns. In those cases, the black cylinder is not just a quiet helper, it is actively preventing what one analysis described as a kind of small scale disaster, where a simple cable choice can undermine an entire system. That is why some consumer explainers emphasize that The Mysterious Black Cylinder On Your Cables Isn, Just For Decoration and that it is helping you avoid disaster by keeping interference in check, a point that becomes obvious once you have seen a problem vanish after adding the right The Mysterious Black Cylinder On Your Cables Isn to the line.

What you should (and should not) do with ferrite cylinders

From a user perspective, the most important rule is simple: leave the cylinder alone and do not cut it off to make the cable look sleeker or easier to route. Removing it can push a marginal setup over the edge, especially if the device relies on that extra filtering to keep interference under control in your specific environment. If a cable with a cylinder feels too bulky, the safer option is to buy a different cable that was designed without one, rather than modifying the existing cord and potentially voiding warranties or creating compliance issues.

On the flip side, if you are troubleshooting interference, it can be worth experimenting with cables that include ferrite beads or adding clip-on rings near the device end of problem cords. Guides to killing power line interference with clip-on ferrite rings show that a well placed core can tame noise that would otherwise plague radios, televisions, and other sensitive gear, and the same principle applies to USB, HDMI, and power leads in a crowded home office. The key is to treat ferrite cylinders as targeted tools rather than magical upgrades, understanding that they solve specific EMI problems but do not replace good cable routing, proper grounding, or quality shielding elsewhere in the system.

Why this tiny component will keep mattering as devices evolve

As electronics continue to pack more processing power and wireless capability into smaller enclosures, the potential for interference only grows, and so does the importance of simple, robust fixes like ferrite beads. Faster data standards push signals into higher frequency ranges that are more prone to radiate, while the spread of smart home devices fills the spectrum with additional sources of noise. In that context, a passive component that can be tuned to soak up specific bands of unwanted energy without adding complexity or latency is likely to remain a staple of cable design for years to come.

At the same time, the quiet presence of these cylinders is a reminder of how much engineering goes into making technology feel effortless. The next time you notice a black bump near the end of a cable, it is worth remembering that it is there to keep your devices and their neighbors from stepping on each other’s signals, not to decorate the cord. From the ceramic chemistry of the ferrite material to the regulatory tests that drive its placement, that small cylinder embodies a long chain of design decisions aimed at making your digital life less noisy, even if you never knew it was working on your behalf.

More from MorningOverview