At the world’s most powerful colliders, physicists are finally catching sight of particles that almost never leave a trace, a “ghost” signal that has haunted theory for decades. The detection of these elusive messengers inside machines like the Large Hadron Collider and CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron is turning a long‑standing prediction into hard data and opening a new way to probe the universe’s most extreme conditions.

I see this moment as a pivot in high‑energy physics: the point where colliders stop being only factories for heavy, short‑lived particles and become laboratories for the faintest whispers in nature, the neutrinos that slip through planets and people as if they were not there at all.

Why physicists chase a “ghost” in the first place

The signal that researchers are now celebrating is not a new kind of magic, it is the long‑sought footprint of neutrinos, particles so shy that trillions pass through every human body each second without a hint of interaction. These neutrinos have earned the nickname “ghost particles” because they barely notice matter, a property that makes them both maddening to detect and uniquely valuable as probes of the most violent processes in the cosmos. When I talk to collider physicists, they describe neutrinos less as ordinary particles and more as messengers that carry unfiltered information from places where light and charged particles are scrambled beyond recognition.

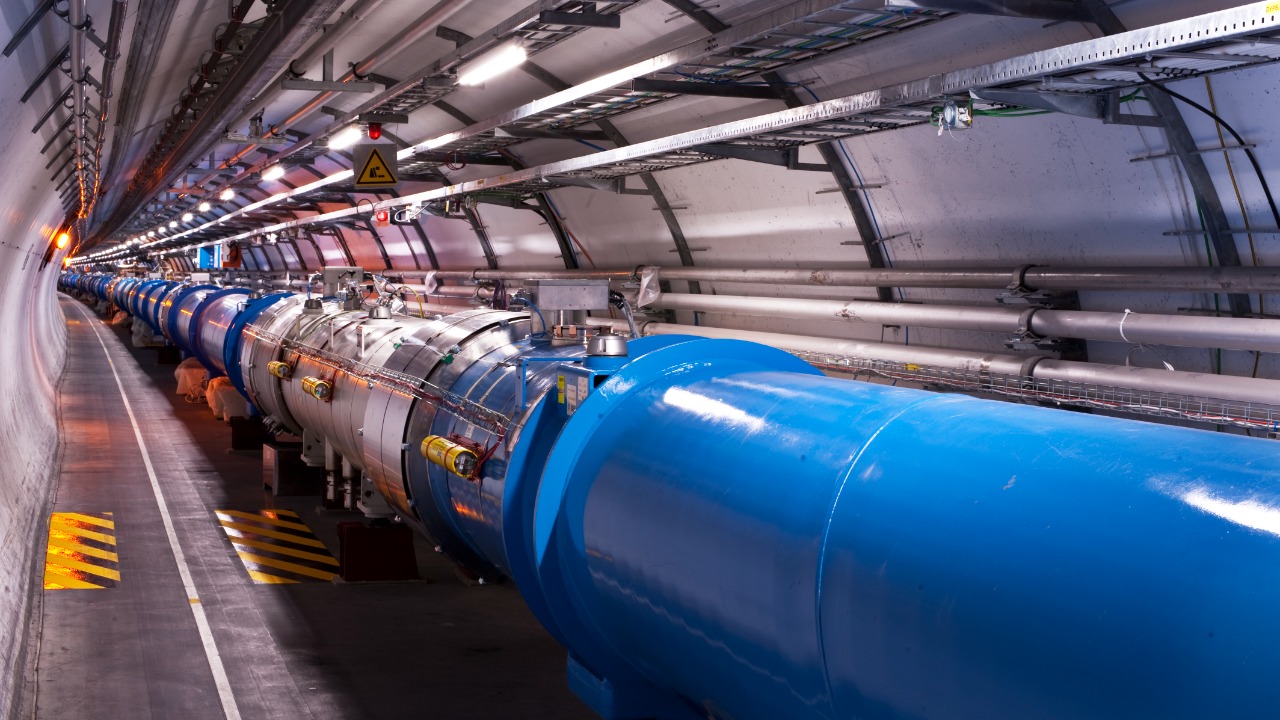

In the context of the Large Hadron Collider and its sister machines, that ghostly reputation is not just poetic branding, it reflects a concrete experimental challenge. Neutrinos are electrically neutral and incredibly light, so they do not curve in magnetic fields and rarely collide with detector material, which is why they were long expected but never directly seen inside a high‑energy collider environment. Earlier work on the Large Hadron Collider’s broader science program highlighted that Neutrinos, nicknamed “ghost particles” because of their elusive nature, permeate the universe yet almost never leave a mark, which is exactly why capturing them at the point of creation inside a collider is such a powerful test of our models.

From theory to trace: how colliders finally saw neutrinos

For decades, neutrinos were detected mainly from natural or engineered beams, such as those produced in nuclear reactors, the Sun, or cosmic ray showers in the atmosphere, while colliders focused on charged debris that was easier to track. The conceptual leap was to treat the collider itself as a controllable neutrino source and to build dedicated detectors in the right place to intercept a tiny fraction of these ghosts as they streamed away from the collision point. That strategy has now paid off, with experiments reporting the first direct evidence of neutrinos produced and observed inside a particle collider, a milestone that shifts neutrino physics from remote observatories into the heart of accelerator complexes.

One of the key steps in this transition came when researchers working with a compact detector near the collision region reported that they had finally seen neutrino interactions in the spray of particles from proton collisions. In coverage of this breakthrough, the detection was framed as scientists finally managing to Scientists Finally Detect Neutrinos in a Particle Collider, a moment that confirmed long‑standing expectations about how often these particles should be produced and how they should behave at energies far beyond those available in reactors or solar experiments.

The Large Hadron Collider’s first “ghost” tracks

Inside the Large Hadron Collider itself, the first hints of neutrinos were not obvious streaks on a screen but subtle signatures in specialized detectors placed along the beamline, far from the main experiments that discovered the Higgs boson. These instruments were designed to sit in the path of particles that shoot forward almost along the beam direction, a region where neutrinos from proton collisions are expected to be abundant yet almost entirely invisible to the central detectors. When the data finally revealed interactions consistent with neutrinos, it marked the first time that these ghostly particles had been directly spotted inside the world’s largest particle accelerator rather than inferred from missing energy or external beams.

Reporting on that achievement described how Ghost particles were detected inside the Large Hadron Collider for the first time, emphasizing that the result opened a new way to investigate the subatomic world using neutrinos produced in controlled high‑energy collisions. For me, the significance lies not only in the technical feat but in the validation of a strategy: by embedding neutrino detectors into the collider infrastructure, physicists have turned a machine built to smash protons into a laboratory for some of the faintest signals in nature.

“Ghostly” neutrinos and the world’s largest accelerator

The story did not stop with a single detection, because once neutrinos were seen at all, the next step was to characterize them and prove that collider‑based neutrino physics could stand alongside more traditional experiments. At the world’s largest particle accelerator, physicists pushed this idea further by presenting detailed results on neutrinos that had energies and trajectories unlike those typically studied in underground observatories. These neutrinos were produced in the same violent proton collisions that generate jets of quarks and gluons, yet they slipped through the main detectors and only revealed themselves in carefully placed instruments downstream.

Those results were showcased at the 57th Rencontres de Moriond Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories, where researchers described how they had spotted Rencontres de Moriond Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories “ghostly” neutrinos racing close to the speed of light inside the world’s largest particle accelerator. By tying the neutrino signal to well‑understood proton collisions, the team could test how these particles interact at energies that mirror conditions in cosmic ray showers, giving collider physicists a new handle on processes that were once the exclusive domain of astrophysical observatories.

The “ghost” haunting CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron

While the Large Hadron Collider grabs most of the headlines, the ghostly theme extends to CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron, a workhorse accelerator that feeds beams into the larger machine and hosts its own suite of experiments. Physicists working with this ring have described how subtle, hard‑to‑pin‑down effects can shape the way energy is distributed and amplified around the accelerator, creating what they call loci where energy is concentrated in unexpected ways. In their language, the “ghost” haunting the machine is not a supernatural presence but a pattern in the beam dynamics that had to be understood and tamed to keep the accelerator performing at its peak.

Coverage of this work explained that Physicists Found the Ghost Haunting the World’s Most Famous Particle Accelerator by analyzing how CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron will reveal loci where energy is amplified. I see a thematic link between this and the neutrino story: in both cases, researchers are chasing signals that are not obvious in raw data, whether they are ghost particles slipping through detectors or ghostlike patterns in the beam that only emerge after careful modeling. In each case, the payoff is a more precise, more stable machine that can push deeper into unexplored territory.

Why collider neutrinos matter for cosmic mysteries

Detecting neutrinos inside colliders is not just a technical trophy, it is a new way to tackle some of the biggest open questions in physics. Neutrinos are woven into theories of how stars explode, how elements are forged, and how cosmic rays propagate through space, yet their properties at the highest energies remain only loosely constrained. By producing neutrinos in controlled proton collisions and measuring how they interact with detector material, collider experiments can test whether these particles behave exactly as the Standard Model predicts or whether there are subtle deviations that hint at new physics.

Earlier discussions of the Large Hadron Collider’s scientific agenda highlighted that neutrinos, described as Neutrinos nicknamed “ghost particles” because of their elusive nature, could help unravel some of the biggest mysteries in the universe. From my perspective, the collider detections bring that promise into sharper focus. They allow physicists to compare neutrinos produced in human‑made collisions with those arriving from the Sun or from distant astrophysical accelerators, checking for any mismatch that might reveal new interactions, hidden particles, or unexpected behavior at extreme energies.

How detectors learned to listen for ghosts

None of these results would be possible without a quiet revolution in detector technology, which had to evolve from catching bright, charged tracks to listening for the faintest of taps from neutrino interactions. Engineers and physicists designed compact detectors that could sit close to the beamline without disrupting operations, using dense materials to increase the chance that a neutrino would finally collide with an atomic nucleus and produce a visible spray of secondary particles. The challenge was to distinguish those rare events from the overwhelming background of other particles and radiation that flood the same region.

In reports on the first collider neutrino detections, the experimental teams emphasized how they had to calibrate their instruments against known signals and then sift through enormous data sets to isolate the handful of events that could only be explained by neutrinos. One account described how Large Hadron Collider for the first time, detectors were tuned specifically to catch ghost particles, showing that with the right design, even the most elusive components of the subatomic world can be brought into view. As I see it, this is a reminder that breakthroughs in physics often depend as much on clever instrumentation as on bold theoretical ideas.

What comes next for ghost signals at the top colliders

With the first ghostly signals now firmly in hand, the obvious question is how far collider neutrino physics can go. Future runs of the Large Hadron Collider and upgrades to CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron will deliver higher intensities and more collisions, which in turn will produce larger samples of neutrinos for dedicated detectors to study. That will allow researchers to map out how neutrino interaction rates change with energy, to search for rare processes that might betray the influence of new particles, and to cross‑check measurements from long‑baseline neutrino experiments that send beams through hundreds of kilometers of rock.

At the same time, the conceptual tools developed to find ghost particles and ghostlike beam patterns are likely to spill over into other areas of accelerator science. The work that identified Most Famous Particle Accelerator loci where energy is amplified in CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron, for example, points toward a future in which machine learning and precision diagnostics routinely uncover subtle structures in beams and detector responses that would once have gone unnoticed. From my vantage point, the ghost metaphor is starting to feel less like a spooky flourish and more like a shorthand for the frontier of sensitivity, the place where signals are so faint that only the most refined instruments and analyses can bring them into the light.

The quiet transformation of collider physics

Stepping back, I see the emergence of these ghost signals as part of a broader shift in how colliders are used. The early years of the Large Hadron Collider were dominated by the hunt for heavy, spectacular particles like the Higgs boson, which announced themselves through clear, high‑energy signatures in the main detectors. Now, as the machine matures, physicists are turning their attention to more delicate questions that require listening for whispers rather than shouts, from tiny deviations in known processes to the rare interactions of neutrinos and other elusive particles.

The reports that chronicled how Ghost Particles were finally detected in a Particle Collider and how Mar “ghostly” neutrinos were spotted inside the world’s largest particle accelerator capture only the first chapter of this transformation. As detectors become more sensitive and analysis techniques more sophisticated, I expect the line between collider physics and astrophysics to blur further, with accelerators not just smashing particles together but also recreating and decoding the faint signals that shape the universe on its largest scales.

More from MorningOverview